Big Plans/Big Risks

Monday, January 6, marks the real beginning of 2014 for most people. Schools reconvene (or not, given the weather here in the upper Midwest); schedules reassert themselves. We realize we have a lot of work ahead of us, and that we have slacked off during the holidays. Chorale began rehearsing our March 16 concert (Bruckner, Mass in E Minor) before Christmas break, but today still feels like a significant marker for us, the beginning of a new season, a door into the future. At December’s board meeting, we talked of coming projects, and made significant, forward-looking decisions; today, we begin to turn those programs and decisions into reality. Repertoire choices, venues, and soloists; budgets, fund-raising, governance-- all aspects of Chorale’s operations kick into high gear, and not just for the coming months: we throw our nets, and our hopes, ‘way into the future.

I heard just a snippet of a radio program on NPR last week, about Chicago’s special business climate, and about the strategies various entrepreneurs employ to achieve success here. Over and over I heard the word “risk”: acceptable risk, too much risk, too little risk. All the speakers seemed to feel that Chicago is a volatile, even brutal, market, requiring big vision and a very high level of risk—requiring a significant leap, to bridge the chasm between the cautious “here and now,” and future achievement. They seemed to be saying, in fact, that caution is likely to lead to failure, and that a surprising degree of recklessness is necessary just to stay in the game. I wish I had heard more, had more context within which to weigh what I did hear. It seemed important to me.

Chorale began twelve and a half years ago with no money and no concrete plans. What we had was a mission: we wanted to rehearse and perform the very best choral repertoire available to us, and we wanted to develop an audience which would support us. We defined ourselves as “amateur” in the best sense of the word: we did this for love, not for individual monetary gain. We felt that amateurs had a right, even an obligation, to sing great music, and we expected to sing it well. Initially, we risked nothing: we simply wanted to please ourselves and our friends. But “rehearsing and performing the very best choral repertoire” turns out to be no small thing: it demands energy, talent, persistence, ambition. Success changes us-- not all at once, but over time: it raises our standards, fosters expectations, invites comparison, criticism, and competition. Success engenders risk: can we handle this repertoire at a good level? Do we sing this piece or that one? Can the singers tolerate, and enjoy, being pushed harder and harder? Will they show up in September to sing the music I choose in May? Am I capable of conducting the works that interest us? Will listeners enjoy and appreciate the programming? How many tickets do we need to sell? How many posters/programs/postcards do we print? Can we afford the postage? Will we meet important deadlines? Can we afford an orchestra? How good an orchestra do we need? Can we afford appropriate soloists? Will they work for what we can pay? Do we perform at new and different venues-- will we draw crowds? Will the acoustics work? Brochure copy, press releases, blog, program notes-- is the writing clear? Can I defend the things I have written? Do they help?

And to paraphrase Robert Shaw: once we have worked so hard to prepare his nest, will the dove land? Will we touch hearts and minds?

Each advance, each development, represents a risk, or constellation of risks, we deal with daily. Often enough, indeed, I feel nostalgic for our naïve early days, when we were pleased that anything at all worked out. When a dream, a plan, a scheme begins to take shape inside me, my litany of risks pops up, and I almost wish the dream would just go away… imagining that neither I nor the group have the energy, the talent, the resources to be thinking so largely and boldly. It happens, though, that the dream seldom does go away; it may harden into a knot and subside into an uncomfortable dormancy, but I can’t escape it.

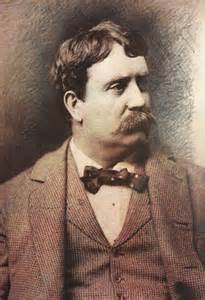

My father admired Chicago architect Daniel Hudson Burnham (1846-1912), and framed a copy of Burnham’s famous creed, which he hung above the toilet in our bathroom. It reads:

Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty. Think big.

Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty. Think big.

My brothers and I memorized this. For good or ill, it has ruled us. Fearful and inadequate though I often feel, I see that it fuels my work and ambitions, regardless of the particular sphere in which I work. Burnham’s words came back to me as I listened to that radio program; and I realized that I ride the horse my father put me on, and have been doing so all along, whether I knew it or not. However humble our building blocks, Chorale “really means it,” is in this for the long haul, and will continue to assert itself, and its vision, with ever-growing insistency.