Robert Shaw's Advice for Conductors

Something I recently found posted on Facebook:

Something I recently found posted on Facebook:

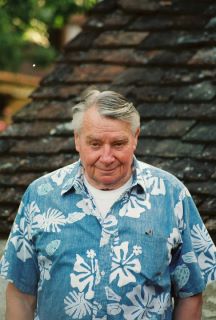

Good Advices for All Conductors (by Robert L. Shaw)

1. Love your singers.

2. Love humanity.

3. Insist on personal and musical integrity.

4. Study your music until you know it as well as the composer.

5. Study your music again and again until you know it as well as the composer.

6. Strive to perfect the technique of music so that the heart of the music may shine through.

7. Love your family.

8. Spend time with your family.

9. Maintain your sense of humor

In its original form, this list is presented in faux-gothic script, centered on the page—like Charlton Heston’s ten commandments. Mr. Shaw always maintained his sense of humor. I would like to add a couple more, from my own experience (it's my blog, after all):

10. Pay attention to what your colleagues are doing.

11. Keep up your instrument.

12. Get outside.

Now for Lutheran catechetical exegesis:

1. & 2. These can be pretty tough. He also said (though apparently did not commit to print) that a nice person could never be a good choral conductor. Mr. Shaw could be pretty rough on his singers, and so can the rest of us. On the one hand—where would we be, without them? They are our voice, and the voice of that humanity he advises us to love. Their physical, intellectual, and emotional gifts transform dots, lines, and circles into Bach and Beethoven. They show up rehearsal after rehearsal, put up with our inadequacies, sing their hearts out, and thank us when it is all over. They also will take advantage of any nuanced understanding we demonstrate regarding their personal situations, and push us to the edge regarding their special needs and desires. They will expect to be favored, complain that they are ill-treated and misunderstood, and be unable to sing week after week because of a cold. But Mr. Shaw is right—if our honest, heartfelt love for them does not triumph, if we cannot keep our appreciation, admiration, and gratitude ever before us, but instead let frustration, fatigue, and impatience get the better of us, if we cannot rescue our hearts from the abyss of disappointment, we will lose them — and then it is time to look for a new profession. Easier I think to “love humanity”—I am an Aquarius, and we are pretty happy to contemplate the glory of the human race and its endeavors; we are not so good with the nitty gritty. Mr. Shaw’s number one really speaks to me.

3. I’m not quite sure if we are to insist on our OWN integrity here, or on that of our singers. Mr. Shaw was a competitive, ambitious man—I can imagine him advising himself to behave. But I do know that he demanded the same of his singers-- if we were caught “cheating” in some sense, we lost his respect—even if that cheating was an expression of fearfulness or inadequacy. He was hard on us, and he was hard on himself. One thing I am sure of—a conductor must never demand of his singers, what he does not demand of himself.

4. & 5. There is no quicker way to derail a rehearsal, than to show up unprepared. It is not OK to think, Oh well, the singers are just starting to learn this, the concert is weeks away, I have time. If one insists on programming first-rate repertoire, one had better work hard to learn it—and work hard at ones presentation of it. Mr. Shaw was not a facile musician—he did not have a lot of formal training, and he had to work very, very hard to learn scores. And he always did. His score preparation and musical discipline were incredible examples of how to do things right.

6. Musicians like to ”feel” things-- technical work and preparation can feel tedious, contrived, lacking in spontaneity; it can seem to destroy the soul of the music, whatever that may be. Or so I thought back when I was eighteen and beginning my serious study of music. I have had wonderful teachers; I have had the undeserved good fortune to recognize and stay away from charlatans. All those wonderful teachers stressed, ad infinitum, the need for objectivity, clarity, patience, repetition, and open-eyed self-criticism in learning this craft. They rarely talked about talent; they talked about putting one note in front of the other. I have sung under many, many conductors who did not really understand the nuts and bolts of their craft, did not know how to solve problems—so when I began singing with Mr. Shaw, I wanted to jump for joy, both because of his demands, and because he knew how to help us meet those demands. He did not always have a clear sense of style or period, and occasionally he drilled awkwardness into us, rather than out of us; but his principles were always sound.

7. & 8. I think Mr. Shaw learned the value of family the hard way. But he learned it, and it sustained him powerfully, to the close of his remarkably long career. Plenty of conductors do not have families, in the conventional understanding of the term, and this may be prudent, given the requirements of career. I think one must broaden the understanding of family implied here—family can take many forms. Whatever that form, it should be expressive of such elements as mutual loyalty, dependability, longevity, support, nurturing-- ones craft and art are not diminished, sucked dry, by this interconnectedness and dependency, but rather fed and nourished by them.

9. I remember Mr. Shaw running really intense, demanding rehearsals, chewing us out, yelling at individuals, accusing us, the whole gamut of questionable personal behaviors of which he has accurately been accused-- and then he would tell a joke or a story, and the whole atmosphere would change, lighten up, and he had us again. Our acceptance and forgiveness of his harshness and his demands were essential to our relationship with him — we knew he was as flawed as we were, we saw ourselves in him; and his often corny, self-deprecating humor and quick wit felt like a sharing of himself. He knew he was nuts; we were glad he knew it, and quick to defend him. l have experienced other, humorless, unforgiving conductors who asked somewhat less than Mr. Shaw, yet really angered me because of the wall they maintained between themselves and their groups. They probably did not intend to do this, but didn’t trust us sufficiently to be one with us when we needed it. When I find myself erecting this same wall, I understand them better—but wish I didn’t do it, wish I had a lighter soul.

10. I think it is very important to attend concerts, even rehearsals, of my colleagues, listen to their CDs, look at their programs, check out their websites. Good bad or indifferent, they all have something, and know something, of which I am unaware; they all have something to teach me. I am very happy to steal from them, and happy to give them credit.

11. We have all these singers at our disposal; we (and the composers) ask a great deal of them. We are critical and accusing when they cannot produce, and impatient when they don’t respond as we expect them to. If we keep continue singing or playing, ourselves, we will not so easily lose sight of the issues which they confront while they work for us, and we will have firsthand information about how they can more closely satisfy our requirements. I think it especially important that we get on the other side of the podium every once in a while—even regularly, if time and energy permit; remind ourselves of what it feels like to be conducted, to be criticized, to be trying to adjust to those around us while reading new music. Singers—instrumentalists, too, I am sure—confront so many problems, so many variables, in practicing their craft; a good choral singer multitasks on the highest level, and part of his task is trying to follow and get along with us, who conduct them. It is good as well to experience for ourselves the visceral and spiritual joy of singing — good to remember why our singers want to be present.

12. The world has changed drastically in the past 100 years. Our crowding, our technology, our speed of travel, our mobility—these things have completely changed the way people live. We know that Beethoven and Brahms loved their walks in the woods, their long summer vacations in rural retreats; I think we can assume that their experience was not that hard to come by. What we don’t seem to realize is that their art was largely shaped by their perception of the natural world around them, a world they could hardly escape, even of they wanted to. Today, we can escape it very easily — and most of us do. We live at some distance from it, and perceive it second-hand. I find that I am most enthused/inspired/enthralled, as well as most clear-headed, when I take the time for daily walks along the lake, through the parks, watching the birds, the clouds, focusing my eyes on the distance this affords me. I have no doubt that it is this love of nature, which, more than anything else, transforms the notes I read in the score, into the shapes and emotions I find and express in musical performance. It is good for my health, and it makes me a better musician and communicator. Many of my colleagues say the same thing about their own experience. But one must make a conscious effort to set aside time and organize ones life in order to enable this.