Where do all those words come from?

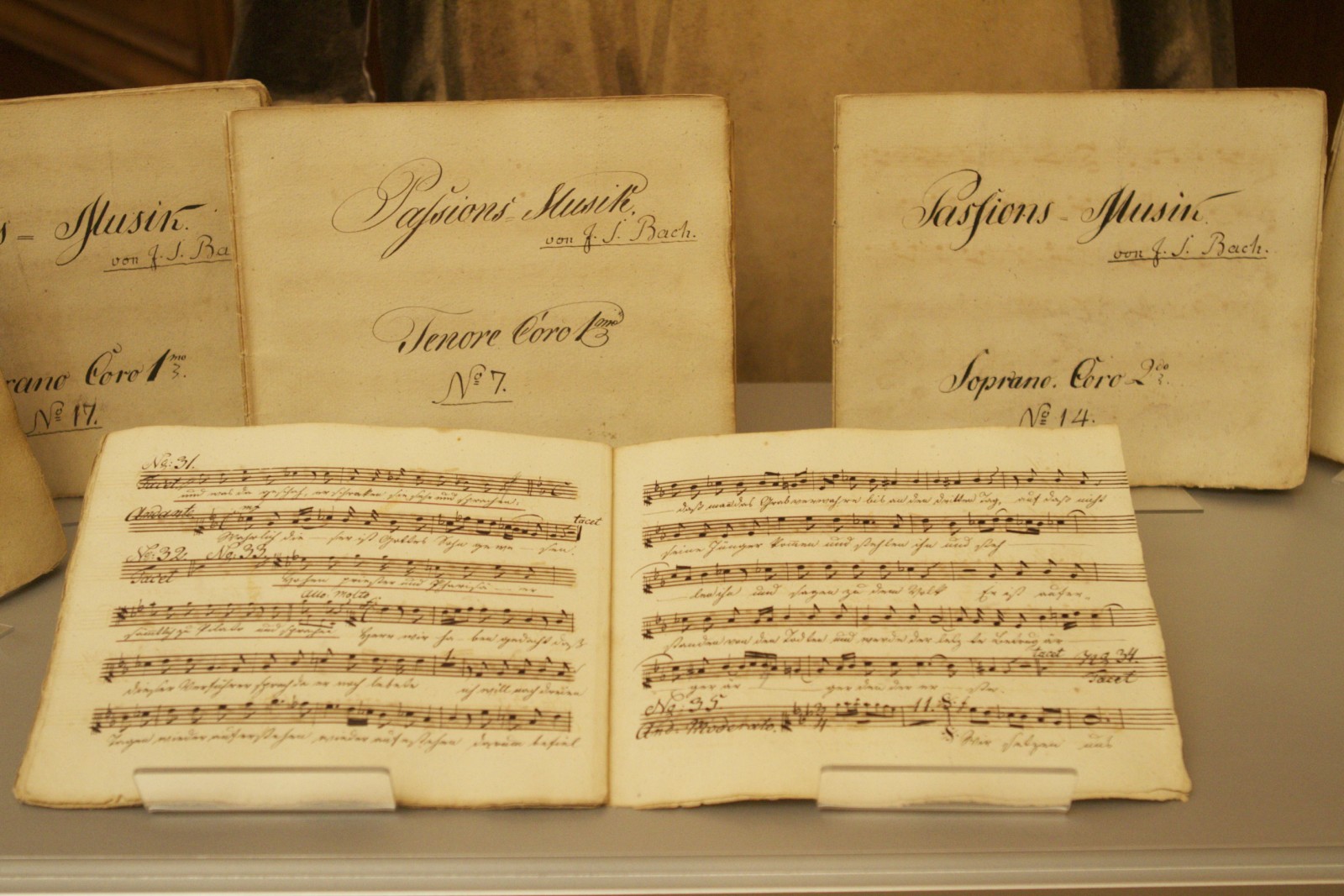

Bach’s setting of the Passion According to St. Matthew was first heard on Good Friday, April 11, 1727, in Leipzig’s Thomaskirche. We twenty-first century listeners and performers must always remind ourselves that this presentation was not a concert: it was a liturgical expansion of the Vespers service, designed to recount the story of the final days of Jesus’ life, as told in chapters 26 and 27 of the Gospel of Matthew the Evangelist (in the 200-year old German translation by Martin Luther), in a manner which would make it comprehensible and meaningful to the Lutheran citizens of Leipzig. Besides the Biblical narrative, Bach set contemporary German poetry, written, adapted, and arranged by his friend and contemporary Picander (pseudonym of poet Christian Friedrich Henrici, 1700-

1764), which functioned as meditations on the Biblical text, and was intended to clarify the meaning of the story, and the motivations and reactions of the characters in the narrative, for the listeners. Presumably these meditations were to guide the understanding and private devotions of the listeners—and in this light, both Picander and Bach served the community as theologians and worship leaders. A third category of text utilized by Bach and Picander is the large number of chorale verses from the Lutheran hymnal, already well known to the listeners.

Bach sets the Biblical text largely in recitative, both secco and accompanied, in a style already familiar to his listeners from opera, especially the operas of Georg Philipp Telemann, who served as musical director for the short-lived Leipzig Opera, 1703-05. The most prominent presenter of this text, of course, is the Evangelist himself, sung by a tenor soloist; but other characters are featured as well, including Pilate, Pilate’s wife, Peter, Judas, the High Priest, a couple of maids, some witnesses testifying at Jesus’ trial—all of them sung by soloists from the ranks of the choir. The choir, sometimes as a single unit, sometimes in two opposed and conversing groups, presents the words of the disciples, the Roman centurions, the priests, and the angry crowd. These crowd scenes, called turba choruses, are not set as recitative, but rather as complex, difficult choral interjections, composed and performed with a character and style suggestive of the scene they portray.

The settings of contemporary poetry are also composed in operatic style, often as paired recitatives and arias, and usually featuring virtuosic writing for principle instruments from both orchestras. Though the actual performers are often the same singers who portray named characters in the biblical sections-- in Bach’s original conception, for instance, the tenor who sings the arias also sings the Evangelist-- these recitatives and arias are meant to be heard as the thoughts and feelings of community members, of observers, in response to

the Biblical narrative. It seems that, in Bach’s own performances, chorus members stepped forward and sang these texts, whereas the words of Peter, Judas, and, perhaps, some others, were sung by singers who were not “community members.” This practice has not, however, been followed since Bach’s own time; the arias are so demanding that specially trained soloists are engaged to sing them. Bach also composes “choral arias”: major movements which set contemplative poetry, sung by the combined vocal forces rather than by soloists.

The chorales, both music and texts, were very familiar to Bach’s listeners. Bach and Picander selected both melodies and verses carefully, to reflect the actions and attitudes being presented in their telling of the story-- so these movements have the dual role of providing comfort and familiarity to the listeners, and introducing yet more reinforcement for the overall themes of the Passion presentation. I have participated in Passion performances in which these movements were actually sung by the audience; but there is no evidence that Bach actually intended this. In some movements, Bach combines chorales, sung by the choir, with arias, sung by soloists—a hybrid procedure which functions on several interlocking levels in the telling of the story.

Odd to think about the words being more important than in the music, especially the music of Bach; but this seems to have been Bach’s own attitude and intent, in his liturgical works: to use music as a means for presenting essential text in the most immediate, dramatic, and comprehensible manner. A worship community could simply mount a reading of the biblical text, add a few hymns and a couple of meditations spoken by a worship leader, and be done with it. This is common practice in many Christian churches on Good Friday, even today. That Bach went so very much further, is his great gift to us.