Bach St. John Passion—The Details

Chorale is now more than half way through our rehearsal period, preparing for our March 27 St. John Passion performance. Most pitches are learned; we work every week with our language coach, Temmo Kinoshita, on German pronunciation and comprehension; dynamics have been planned and written in, and rehearsed. We have begun working on movement-to-movement transitions. After an initial re-placement of all the voices, we are settling in to an appropriate vocal sound and production. Though still somewhat below tempo on the faster movements, we are becoming more fluent each week; as pitches and rhythms become more solid, this fluency becomes easier and less taxing.

Chorale is now more than half way through our rehearsal period, preparing for our March 27 St. John Passion performance. Most pitches are learned; we work every week with our language coach, Temmo Kinoshita, on German pronunciation and comprehension; dynamics have been planned and written in, and rehearsed. We have begun working on movement-to-movement transitions. After an initial re-placement of all the voices, we are settling in to an appropriate vocal sound and production. Though still somewhat below tempo on the faster movements, we are becoming more fluent each week; as pitches and rhythms become more solid, this fluency becomes easier and less taxing.

On the production front: we have completed our detailed schedule for tutti, orchestra-chorus-soloist rehearsal, subject, of course, to change (on the spot!) during our actual rehearsals. Poster and postcard designs are completed and at the printer. Transportation and accommodations for soloists and instrumentalists coming from out of town are in process. Radio ads are written and scheduled with WFMT and WBEZ. Transport of our continuo organ is being planned as I write.

Chorus morale is good. We recognize the St. John Passion as one of the great works of art for good reason: it is fantastically involving, motivating, challenging in the best possible ways. The deeper the singers get into it, the more enthusiastic they are, and the more swept up they feel. Great music is at least as fulfilling for the performers, as it is for the listeners. We actually have our fingers in it, we experience the mind of Bach, feel every twist and turn of the passion narrative. The problems with the work, with the anti-semitism of the world for which Bach composed it, become real to us; and in coming to terms with this, we experience Bach’s humanity, and the realities of the world in which he lived, and in which we live. Performing this work is a full-frontal confrontation with our own tragically flawed humanity—as we sing in the eleventh movement chorale, “Wer hat dich so geschlagen?... Ich, ich .” “Who has done this to you? I have.” Hard words to hear, and Bach sets them with searing intensity. His art in bringing the story to life is breath-taking.

Part of the genius and greatness of Bach lies in his ability to transcend the particulars of his time and place, and of his German Lutheran milieu. He composes a work which speaks to all people, of all times, regardless of their national or religious identity. He reaches us, touches us, on the deepest and most fundamental level. From the majestic but ominous opening chorus, to the comforting final chorale, Bach involves us in the human story, and reminds us of our place in that story.

Clarity. We must be together.

Clarity. We must be together.

I sang with the Oregon Bach Festival for about ten summers—a wonderful experience for me, on many levels. I met good friends, enjoyed the Pacific Northwest, and ate incredible food. It was an idyllic chapter in my life, one I will always cherish. Most importantly, I sang a lot of Bach: the “Big Three” (the Mass in B Minor, and the Passions According to Matthew and John) and many, many cantatas, all under the leadership of Helmuth Rilling, who was a master of this repertoire, and an inspirational teacher. His rehearsals with us were focused, efficient, and very informative—he knew how to get what he wanted. Occasionally he would stop mid-rehearsal and, with exasperated patience, ask, “What is most important?” Then answer his own question: “Clarity. We must be together.” He had a funny, telling gesture-- the choir would be lurching its way enthusiastically through some passage, and he would stop us, grimace, wipe his hands on both sides of his mouth—as though cleaning off drool or spilled food. We’d laugh, but the point was made: without clarity, our energy resulted in a wasteful mess.

“Clarity. We must be together.”

I sang with the Oregon Bach Festival for about ten summers—a wonderful experience for me, on many levels. I met good friends, enjoyed the Pacific Northwest, and ate incredible food. It was an idyllic chapter in my life, one I will always cherish. Most importantly, I sang a lot of Bach: the “Big Three” (the Mass in B Minor, and the Passions According to Matthew and John) and many, many cantatas, all under the leadership of Helmuth Rilling, who was a master of this repertoire, and an inspirational teacher. His rehearsals with us were focused, efficient, and very informative—he knew how to get what he wanted. Occasionally he would stop mid-rehearsal and, with exasperated patience, ask, “What is most important?” Then answer his own question: “Clarity. We must be together.” He had a funny, telling gesture-- the choir would be lurching its way enthusiastically through some passage, and he would stop us, grimace, wipe his hands on both sides of his mouth—as though cleaning off drool or spilled food. We’d laugh, but the point was made: without clarity, our energy resulted in a wasteful mess.

Bach’s St. John Passion presents us with three fronts upon which we must fight for clarity: language, pitch, and rhythm. The first is the singers’ particular battle: given a text, we must make that text clear to our listeners. We do well to remind ourselves that Bach's principle job in Leipzig was to save souls; he utilized pitch and rhythm to clarify his presentation of text, rendering it more effective and compelling than it would be as bare, recited words. The Passion narrative, and its power to change the hearts of his parishioners, was his highest priority. Bach never composed less than glorious music, and his musical invention and imagination cannot really be separated from his text setting; but his priority wass to get the text out where listeners can hear it and be edified by it.

Bach compiled his text from three sources: the Passion narrative from the Gospel of John, contemporary poetry which explores emotional and theological questions raised by this narrative, and chorale verses which were familiar to his target audience. Each text type requires careful presentation by the performers. Some ensembles, honoring Bach’s primary purpose in presenting this work, translate these texts into the native language of the performers and listeners; most ensembles, though, sing Bach’s work in its original German, out of consideration for Bach’s skill in setting that language. The word accents, rhythms, and sentence structure of German determine, to a startling degree, Bach’s rhythmic patterns and melodic contours; and these patterns and contours, translated into musical gesture, don’t necessarily fit with other languages.

Modern performers, and listeners, choose to experience Bach at his musical best; we are no longer so compelled by his evangelical fervor, that we are willing to compromise his art. Nonetheless, it helps me, as singer and as conductor, to assume that projection of the text is paramount, and that the rest of what happens stems from accomplishing this. One must assume that Bach fully intended that his listeners understand the words he had set-- and that he succeeded in bringing this about. The spaces in which Bach performed were highly reverberant, constructed of stone, glass, and wood; clear verbal projection was very difficult. Voices had to be relatively free of vibrato by modern standards, clear and unwavering in pitch, bright and somewhat “cutting” in quality. They had to be light enough in production that they could produce the coloratura Bach required of them, clearly and in tempo. Loud, heavily produced voices would cloud the acoustic, leading to the loss of details which make words comprehensible. A detached, almost staccato articulation would also have been necessary; a legato approach, in choral singing especially, would caused details in a reverberant acoustic to smear together, distorting on all three fronts: language, pitch, and rhythm.

German is a good language to sing, in dealing with such requirements. The consonants are strong, the vowels are clear, and there are “stops” between words—all of which contribute to a text’s comprehensibility in a difficult acoustic environment. And the accompanying instrumentalists, responding to the singers’ priorities, provide the same sort of lightness, articulation, and word-influenced accents—in fact, I suspect that an awful lot of what we now expect from “baroque” instrumentalists, in terms of style, articulation, volume, etc., is based not only in the physical nature of their instruments, but in the needs of the singers who collaborated with these players almost three hundred years ago, and who insisted that their words be heard and understood. If singers and instrumentalists alike are compelled to communicate the Passion text to listeners, they will of necessity rein in and channel their resources, expending their energies far differently than they would be required to do in concerted music composed a hundred years and more later, when orchestra size and volume, as well as performance halls, had changed to such a degree that composers were confronted with a very different set of priorities.

Experiencing Bach’s St. John Passion as New Music

Were Bach alive now, or Josquin, or Palestrina, or Brahms, or Mozart, what would they compose? and why would they compose it?

Bach’s setting of the Passion According to St. John was first heard on Good Friday, 1724, in Leipzig, Germany. The performance was not a concert; it was a liturgical expansion of the Lutheran Vespers service. The text was in German, the language of its performers and listeners. Some passages were Biblical, in the translation by Martin Luther; some were contemporary devotional poetry. Much of it was the texts of hymns with which the listeners were intimately familiar. With the exception of the hymn tunes, all of the music was “modern”—newly composed, much of it specifically for this event. Bach tinkered with this Passion setting throughout the rest of his life and career —tried different choruses and arias, different poetry, different chorales. He never settled on a definitive version; that which is usually presented today is a thoughtful combination of at least two versions, and was never actually heard during his lifetime.

Bach’s musical setting of the Passion According to St. John, in its day, was immediate and purposeful. Bach focused his art, invention, and craft, not on creating a timeless work of art, but on enhancing the worship life of his community. And it seems clear, from the casual, offhand way he treated most of his manuscripts, that Bach never anticipated the interest shown in this liturgical work after his death. We, who experience this work nearly three hundred years after its first performance, are not Bach’s target listeners and performers. We treat his works with far more reverence, than he did.

I envy those who heard Bach’s works as new compositions. I imagine their anticipation, their pleasure and satisfaction, week by week, as new cantatas appeared, and as Bach performed new works, or improvised on old ones, at the organ or harpsichord. Our experience is so different-- we hear his works completely out of context, largely divorced from the religious and social worlds for which they were composed. We hear them as concert works, as “classical music,” something separate from the music that surrounds us in our daily lives, something that exists in a bell jar, to be appreciated and enjoyed as objects, much as we view paintings and sculptures in museum galleries. We focus on their history, on informed performance practice, on musical gesture and rhetorical language. We try, through exhaustive study and practice, to perform them as Bach imagined them, and to understand Bach’s genius and still-vital appeal, across centuries of change.

But we can never experience Bach as his original listeners did. No matter how hard we work to duplicate the physical conditions of his original performances, we can never be his original audience. We are, at best, successfully costumed and equipped re-enactors. So why put such emphasis and care into our performances of this music? I frequently ask myself this, and related questions, when studying and performing music of earlier times. Were Bach alive now, or Josquin, or Palestrina, or Brahms, or Mozart, what would they compose? and why would they compose it?

It is not healthy to despise the present while worshiping the past—one is left culturally homeless and disconnected, if one cannot embrace ones own world. Chicago Chorale devotes a sizable portion of its energy to the performance of contemporary choral music, by living composers, in an attempt to balance past and present. By focusing on the best and most communicative choral music we encounter, from any historic period, we discover deeper connections, contexts, and meanings, than the particulars of era or circumstance would suggest.

Opening the Door to the St. John Passion

Chorale has embarked on our preparation of J. S. Bach’s St. John Passion. Our performance doesn’t occur until March 27, so we should have plenty of time to learn and polish it; nonetheless, it is a daunting work, requiring our utmost discipline and commitment.

Chorale has embarked on our preparation of J. S. Bach’s St. John Passion. Our performance doesn’t occur until March 27, so we should have plenty of time to learn and polish it; nonetheless, it is a daunting work, requiring our utmost discipline and commitment. First performed in 1724, it is shorter and more streamlined (just shy of two hours) than Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (three hours), and exists in several versions, evidence that Bach was experimenting with the form in composing this particular work. The later Matthew Passion is more complete and balanced in its presentation of all aspects of the Passion narrative, and exists in an autograph form which is indisputably Bach’s final word on the work. Modern audiences often lack the patience to sit through unabridged performances of the Matthew Passion, and prefer the earlier John Passion for its driving, dramatic energy.

In the Christian tradition, the “Passion” is the narrative, common to the four gospels, recounting Jesus’ suffering, physical and spiritual, between the night of the Last Supper, and his crucifixion, the following afternoon. The word itself is based upon the Latin noun passio: suffering, and shares this root with our word “patience.” Christians commemorate the Passion during Holy Week, which begins on Palm Sunday and ends the following Saturday at midnight. Following a tradition dating back to the 4th century, most Christian denominations read one or more narratives of the Passion during Holy Week, especially on Good Friday. In some denominations, these readings are communal, with one person reading the part of Christ, another reading the descriptive narrative, others reading various smaller characters, and either the choir or the congregation reading the parts of crowds and other bystanders.

First movement. “Parte Prima”

The words began to be intoned (rather than just spoken) at least as early as the 8th century. This chanting of the text may have been freely interpretive in the beginning, but within two hundred years manuscripts began to specify exact notes to be sung. By the 13th century different singers performed specific characters in the narrative (as in the communal readings described above), a practice which became fairly universal by the 15th century, when polyphonic settings of the crowd scenes began to appear also. By the 16th century, Passion settings had evolved into a highly developed genre, with a number of different sub-genres, composed by the prominent composers of the time. Martin Luther disapproved of the genre, writing, “The Passion of Christ should not be acted out in words and pretense, but in real life.” Nonetheless, sung Passion performances were common in Lutheran churches right from the beginning of the Reformation period (1517), in both Latin and German, and by the 17th century had evolved into the “oratorio passion” sub-genre, which included instrumental accompaniment, interpolated texts, other Scripture passages, Latin motets, chorales, arias, and recitatives.

J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew and St. John Passions are the best known of this latter type; but passion composition by no means ended with his death. The form continued to be very popular in Germany throughout the 18th century—Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, composed over twenty settings, himself. Interest in Passion composition waned during the 19th century, but took on new life in the 20th, with major settings by Krzysztof Penderecki, Arvo Pärt, Tan Dun, Osvaldo Golijov, Mark Alburger, and Scott King. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar and Stephen Schwartz’s Godspell contain elements of the traditional passion accounts, as well.

Bruce Tammen’s score. A lifelong companion!

Looking ahead to 2020: How We Do It

Chicago Classical Review has honored Chorale’s March 2019 performance of Vigilia, by Einojuhani Rautavaara, with the #2 position on their “Top Ten Performances of 2019” list. Fantastic, that a volunteer group, operating on a shoestring budget, should be recognized in this way.

Chicago Classical Review has honored Chorale’s March 2019 performance of Vigilia, by Einojuhani Rautavaara, with the #2 position on their “Top Ten Performances of 2019” list. Fantastic, that a volunteer group, operating on a shoestring budget, should be recognized in this way. We all know that the CSO, Lyric Opera, Music of the Baroque, Chicago Opera Theater, Bella Voce, and other local, professional ensembles consistently produce world-class performances of great music; to appear on this list with them is something we will always treasure.

Whatever the level we reach in our performances, our work reflects certain core disciplines and procedures; we don’t go at this haphazardly, depending on luck and inspiration. As Robert Shaw often said in rehearsals, the dove won’t land, if you don’t make a good nest for him. What happens in performance reflects an immense, unseen investment. I have been reminding myself, over this midwinter break, of just what those disciplines and procedures are:

1. Auditions: though Chorale does not pay its singers, we audition our singers very carefully. They must have exceptional ears for pitch; they must read music; their tone must be warm, flexible, and easily produced; they must be able to negotiate their vocal registers cleanly. They must demonstrate that they can think musically, learn and perform significant repertoire, and pronounce sounds that do not occur in English. And they have to know when and how to back off and put ensemble values first. I am cautious in considering large, colorful voices, whose owners clearly wish to sing opera or other solo work—not because the voices are not good, but because I want to be sure the singers understand and enjoy choral singing.

2. Placement within sections: singers must be positioned where they can sing most comfortably and effectively, and contribute most positively. Each section must finally sing as a unit, whatever the contents of the section, voice by voice; I never want us to sound like a collection of individual voices and personalities.

3. Repertoire: first, it must be worthy literature-- we sing it because it is good, reflecting the highest aspirations of great composers, not because it reflects or inspires particular seasonal, ethnic, or religious sentiments. Second, it must be repertoire suited to Chorale—to our size, to our talents, to our available rehearsal time, to our audience. We want to be stretched; we also want to be reasonably sure we will accomplish the stretching. We want to stretch our audience, as well-- but want them to enjoy what they hear. Having chosen to be high-brow, we still want to be within reach.

4. Venues: the spaces in which we sing are a big part of the overall musical experience, both acoustically and visually. We seek venues which enhance our sound, and enhance our understanding—for the singers as well as for the audience. On a practical, and sometimes conflicting, level, we also seek venues we can sell to audiences—there are many beautiful spaces in Chicago to which we cannot attract listeners. We need paying audiences. We have been fortunate in finding spaces which satisfy both requirements, and always have our eyes and ears open.

5. Strong mission: finally, we need to believe powerfully in what we are doing. Singers, workers, board members, donors, will not continue to contribute if they are not committed to what we are doing-- or if they sense that I am not committed. We ask a great deal of our singers, knowing they can go elsewhere, or stop singing altogether, if they are not fed by the Chorale experience. We need to provide a milieu in which they feel supported and stimulated on many fronts. They have to be proud of what they are doing. Similarly, our many volunteers, singers and non-singers, have to be proud of our product and our ethos; and our board members have to feel that their time and energy is profitably spent. And everyone involved needs to be confident that we will not fail to reach and maintain a certain level of performance, and that we will always strive to be better than we currently are. We can’t afford to be less driven, or less idealistic, than we are.

I believe that the best music is made by people who love what they are doing, no matter their day job. And I am convinced that people who make good music as well as they can, must be the happiest people. This conviction underlies all of my work with Chorale. I am glad our work is bearing fruit, and that others are being fed.

Friede auf Erden: Peace on Earth

The largest, most complex and demanding work on Chicago Chorale’s upcoming Christmas concert is Arnold Schoenberg’s Friede auf Erden.

The largest, most complex and demanding work on Chicago Chorale’s upcoming Christmas concert is Arnold Schoenberg’s Friede auf Erden.

Born into a lower middle-class Jewish family in Vienna in 1874, Schoenberg was largely self-taught as a composer, but came to be considered one of the most important and influential composers of the twentieth century. Active also as a music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter, he was associated with the Expressionist movement in German poetry and art. His works were considered degenerate and modernist by the Nazi Party. While vacationing in France with his family, in 1933, he was warned that returning to Germany would be dangerous. He and his family immediately left for the United States, where he lived for the rest of his life, teaching at UCLA.

In 1898 Schoenberg converted to Christianity in the Lutheran church, partly to strengthen his attachment to Western European cultural traditions, and partly as a means of self-defense during a time of resurgent anti-Semitism. In 1933, the same year he moved to the U.S., he returned to Judaism, convinced that his racial and religious heritage was inescapable, and to declare an unmistakable position opposing Nazism.

Schoenberg composed Friede auf Erden, setting a text by Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, in 1907. The first verse describes Jesus’ birth, while the second depicts the reality of war and bloodshed. The third and fourth verses return to hope and peace, and the dramatic conclusion suggests a vision of heavenly possibility. The compositional style reflects the period in Schoenberg’s life when his highly stylized, late-Romantic idiom was being transformed into a more rigidly structured, atonal Expressionism, and powerfully expresses the tumultuous aesthetic change taking place. The piece received its premier performance, by the Vienna Singverein, in 1911, and though he had indicated in the earliest sketches that the music was meant to be performed a cappella, Schoenberg was obliged to create an orchestral accompaniment for the concert, to support the incredibly challenging vocal writing. Chorale will perform the work in the original, unaccompanied version. Though long regarded as among the most difficult works in the choral canon, it is revered as one of the greatest modern works, and is performed frequently. Anton Webern, one of Schoenberg’s most famous and successful students, wrote to him in 1928, “Have you even heard your chorus at all? In that case, do you know how beautiful it is? Unprecedented! What a sound!”

Schoenberg eventually became disillusioned with the concept of universal harmony and peace, and his choral evocation would later elicit a somber remembrance from the composer. He wrote in 1923 that Friede auf Erden was “an illusion created in [my] previous innocence,” one created when he still believed such a unity was possible.

Schoenberg died in Los Angeles in 1951; his ashes were returned to Vienna, and interred there, in 1974.

Self-Portait.

The Rose and the Lamb.

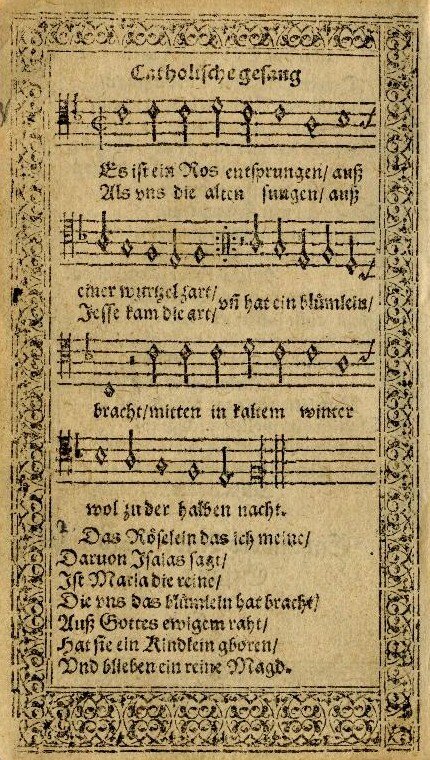

Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming (Es ist ein Ros entsprungen) is one of the best-known of numerous German carols to be adopted whole heartedly by the English-speaking world. The music first appeared in print in the Speyer Hymnbook 1599, and is most commonly sung in the version harmonized by the German composer Michael Praetorius in 1609.

Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming (Es ist ein Ros entsprungen) is one of the best-known of numerous German carols to be adopted whole heartedly by the English-speaking world. The music first appeared in print in the Speyer Hymnbook 1599, and is most commonly sung in the version harmonized by the German composer Michael Praetorius in 1609.

The text has been in use since the 15th century. Based upon Isaiah 11:1, “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots,” it depicts Mary as a rose sprouting from the stem of the Tree of Jesse, a symbolic device that indicates the descent of Jesus from Jesse of Bethlehem, the father of King David. Unlike other German chorales of this period, which were compiled and intended for Protestant worship subsequent to the Lutheran Reformation (1517), this hymn has enjoyed popularity among both Roman Catholics and Protestants.

In the version of the carol which Chorale will sing, Swedish composer Jan Sandström (b.1954) utilizes Praetorius’s four-part chorale setting (sung in its entirety by choir I) as a slow moving cantus firmus, within a freely composed eight-part accompaniment (choir II, humming or singing on a neutral syllable). The overall effect is that of an “acoustic halo”(Stefan Schmöe), a “timeless, atmospheric, dream-like soundscape of poignantly dissonant polyphonic strands “(John Miller). Effectively, Sandström builds a shimmering, acoustically lively performance space to house Praetorius’s jewel of a piece.

Another jewel on Chorale’s Christmas program is the 1982 setting by John Tavener (1944-2013) 1982 of The Lamb, the third poem in William Blake’s Songs of Innocence, first published in 1789. The words are:

Little lamb, who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee,

Gave thee life, and bid thee feed

By the stream and o’er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing, woolly, bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice?

Little lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

Little lamb, I’ll tell thee;

Little lamb, I’ll tell thee:

He is called by thy name,

For He calls Himself a Lamb.

He is meek, and He is mild,

He became a little child.

I a child, and thou a lamb,

We are called by His name.

Little lamb, God bless thee!

Little lamb, God bless thee!

The lamb in the poem symbolizes Jesus Christ as identified by John the Baptist in John 1:29, “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.” Though not specifically an Advent or Christmas text, Blake’s poem invokes the image of the little child, Jesus, as well as the animals around the manger, and this setting is usually sung at Christmas. Tavener’s music-- simple, poignant, somewhat melancholy—presents both the innocence and joy of the scene, and the tragic loss of that joy and innocence in Blake’s companion volume, Songs of Experience, which inevitably lurks in the background.

"I Wonder as I Wander," an American Classic

In our upcoming Christmas concert, Chorale will sing a number of well-known Christmas songs arranged for 4-part choir. Among these is “I Wonder As I Wander,” written by folklorist John Jacob Niles (1892-1980), and based on a song fragment he heard while traveling in the southern Appalachians.

In our upcoming Christmas concert, Chorale will sing a number of well-known Christmas songs arranged for 4-part choir. Among these is “I Wonder As I Wander,” written by folklorist John Jacob Niles (1892-1980), and based on a song fragment he heard while traveling in the southern Appalachians.

Niles was born in Louisville, Kentucky, into a musical family. As a young man, he traveled through the Appalachian Mountains, working as a surveyor and transcribing folksongs he encountered along the way. After service in World War I, he studied music formally, eventually committing himself to what we now term ethnomusicology, collecting and transcribing folk songs, and researching and building folk instruments. He is also well-known as a composer and performer of music in the folk idiom, informed by what he collected.

In notes for an unfinished autobiography, Niles writes:

“I Wonder As I Wander” grew out of three lines of music sung for me by a girl who called herself Annie Morgan. The place was Murphy, North Carolina, and the time was July 1933. The Morgan family, revivalists all, were about to be ejected by the police, after having camped in the town square for some little time, cooking, washing, hanging their wash from the Confederate monument and generally conducting themselves in such a way as to be classed a public nuisance. Preacher Morgan and his wife pled poverty; they had to hold one more meeting in order to buy enough gas to get out of town. It was then that Annie Morgan came out—a tousled, unwashed blond, and very lovely. She sang the first three lines of the verse of “I Wonder As I Wander.” At twenty-five cents a performance, I tried to get her to sing all the song. After eight tries, all of which are carefully recorded in my notes, I had only three lines of verse, a garbled fragment of melodic material—and a magnificent idea.

Based on this fragment, Niles composed the version of "I Wonder as I Wander" that is known today, extending the melody to four lines and the lyrics to three stanzas. His “folk composition” process caused confusion among listeners and singers, many of whom believed the piece to be an authentic folk song, anonymous in origin. Niles went to court to establish his authorship, and charged other performers royalties to perform it.

Chorale has chosen to sing the piece as arranged by British composer and conductor John Rutter (b. 1945). One of the best-known and most successful composers working today, Rutter is particularly noted for his carols, both his original compositions and his arrangements.

The New Russian Choral School (1900-1917)

Russian Orthodox liturgical music constitutes a regular component of Chicago Chorale’s repertoire. We sing individual motets, or major works, drawn from the rich body of music composed during and after the very fertile period represented by the New Russian Choral School, roughly 1900-1917.

Chesnokov, Rachmaninoff, and Gretchaninoff

Russian Orthodox liturgical music constitutes a regular component of Chicago Chorale’s repertoire. We sing individual motets, or major works, drawn from the rich body of music composed during and after the very fertile period represented by the New Russian Choral School, roughly 1900-1917. Composers of that school, including Pavel Chesnokov (1877-1944), Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943), Alexander Gretchaninoff (1864-1956), drew their inspiration from Old Church Slavonic chant and Russian choral folk song, departing from the preceding century and a half of domination by Italian and German models. Led by musicologist Stepan Smolensky, who headed the Moscow Synodal School of Church Singing and pioneered the historical study of ancient chant, these composers created an entirely Russian choral style marked by an endless array of dynamic nuances and choral timbres.

This liturgical music, for religious reasons, was not accompanied by instruments, and as such adapts well to the needs of choirs who are on tight budgets. The composers, inspired by Russia’s brilliant choral culture, were very creative at combining various voice types and ranges, heard in lively, resonant acoustics, to create a virtual orchestra of voices. And the repertoire is easily adaptable to non-liturgical performance: extensive liturgies can serve as major works for concert presentation, while the smaller, more intimate motets work well combined with other repertoire in church and concert settings. The harmonic idiom, vocal characteristics, and overall romantic, passionate character of the music are easily accessible to American audiences and choral ensembles.

Some of this music was known outside of Russia before the 1917 revolution, and some was smuggled out afterward. Despite the fact that scores were often inaccurate, with stilted English translations, many choirs performed the small number of pieces that were available, and clamored for more. At the end of the Cold War, a flood of music from Russian libraries became available, and has subsequently been released in the United States in good editions, with easy-to-use transliterations of the Old Slavonic texts, mostly due to the conscientious, painstaking work of Vladimir Morosan and his publishing house, Musica Russica, based in California.

Chorale will perform three short examples of this genre on our Christmas concerts. The first, Spaseniye sodelal (Salvation is Created), by Chesnokov, is a communion hymn, based upon a cantus firmus derived from Kievan chant. Chesnokov composed a cycle of ten such hymns, most of them harmonized settings of traditional chant melodies.

The second, Shestopsalmiye (The Six Psalms), is movement 7 of Rachmaninoff’s Vigil, Opus 37. Though part of a major work intended for performance leading up to any major church feast, its text consists primarily of the words proclaimed by the angels to the shepherds, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will to men,” in the second chapter of the Gospel of Luke, verse 14.

The third, Nine otpushchayeshi (Lord, Now Lettest Thou), is Gretchaninoff’s setting of the Song of Simeon, a regular element of the Vespers Service. According to the second chapter of the Gospel of Luke, verses 25-32, Simeon, a righteous old man, has been seated in the doorway of the Temple awaiting the Messiah. Mary and Joseph bring the infant Jesus to the Temple, and Simeon, though blind, senses his presence and import, and declares himself ready to die. Though quite short, Gretchaninoff’s setting packs a wallop, and is generally considered one of his finest works.

O magnum mysterium

This year’s program is built around three pillars—three settings of the O magnum mysterium text: one by the Renaissance composer Tomás Luis de Victoria, one by twentieth century French composer Francis Poulenc, and, finally, one by contemporary Basque composer Javier Busto. The text, from the Liber Usualis, is the responsorial chant for the Matins of Christmas, and has inspired many choral composers with its expressive beauty:

Chorale is four weeks into our Autumn rehearsal period, preparing our Advent/Christmas program. We will perform in Hyde Park, and at the Ravinia Festival, the weekend of December 14-15. We presented such a program last year, for the first time, but only at Ravinia. The audience turnout and enthusiasm thrilled us (both performances sold out!), but we felt badly about excluding many of our regular, Hyde Park-based supporters: the trip from the South Side, to near the Wisconsin line, feels like crossing into another world, and is difficult for some of our supporters even to contemplate. So we’ll present two concerts in Highland Park, Saturday at 5 and 7 PM, and one concert in Hyde Park on Sunday, at 3 PM.

This year’s program is built around three pillars—three settings of the O magnum mysterium text: one by the Renaissance composer Tomás Luis de Victoria, one by twentieth century French composer Francis Poulenc, and, finally, one by contemporary Basque composer Javier Busto. The text, from the Liber Usualis, is the responsorial chant for the Matins of Christmas, and has inspired many choral composers with its expressive beauty:

O great mystery,

and wonderful sacrament,

that animals should see the newborn Lord,

lying in a manger!

Blessed is the virgin whose womb

was worthy to bear

the Lord, Jesus Christ.

Alleluia!

In liturgical performance, the chant text is followed by an Alleluia. Poulenc, alone of our three composers, omits the Alleluia, perhaps because the dark, troubling quality of his setting would be disturbed by the addition of an Alleluia. I have read nothing about this omission from Poulenc’s own pen; we just have to assume he knew what he was doing. By this time in his life (this motet was published in 1952), Poulenc had deeply reconnected with his Christian faith, and was composing numerous settings of Christian texts, large and small. This small piece is undoubtedly one of his finest choral compositions, beloved by choirs the world over.

Francis Poulenc

Victoria’s setting, from 1572, while similar in tempo and contemplative quality to Poulenc’s, has none of the troubled darkness of the later work. Victoria focuses on the humble manger scene, transfused with wonder and mystery, and ends with an exuberant, dance-like series of Alleluias, as though the shepherds and their animals are dancing for joy. One of the greatest composers of the Renaissance period, Victoria, a Spaniard, studied and worked for a time in Rome, before returning to Madrid, where he spent his career in service to the royal family.

Tomás Luis de Victoria

Javier Busto was born in Hondarribia, Basque Country, Spain, in 1949, and attended medical school, becoming a family doctor, a profession he has continued to practice up to the present. He began composing and conducting choral music while in school, and has maintained a dual career, while continuing to live in the same region in which he was born. His setting of the O magnum mysterium text, even more than Victoria’s, expresses the observers’ ardent joy at witnessing Jesus’ birth, progressing from the hushed mystery of the birth itself, through the witness and adoration of the animals, and fairly exploding into a fanfare-like Alleluia at the end.

Occurring at the beginning, middle, and end of our program, this text provides a framework which the balance of our music builds on and decorates, and on which it comments. These inspirational settings give performers and audience a lot to chew on and contemplate, as we explore the beauty of the Christmas season.

Color as Music

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) is one of the 20tth century’s most important composers. He began writing music at the age of seven, and entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1919 at the age of eleven, where he studied organ with Marcel Dupré and composition with Paul Dukas. He was also influenced by the works of Stravinksy and Debussy.

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) is one of the 20th century’s most important composers. He began writing music at the age of seven, and entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1919 at the age of eleven, where he studied organ with Marcel Dupré and composition with Paul Dukas. He was also influenced by the works of Stravinsky and Debussy.

The motet O Sacrum Convivium! was composed in 1937, on the eve of World War II, when Messiaen was twenty-nine years old. Though much of his work is overtly Christian in content, this is his only unaccompanied liturgical work. He later wrote of his belief that plainsong was perfect and unsurpassable as liturgical expression, and repudiated this early work, stating that he had moved on from it, both stylistically and philosophically. The texture of the work shares similarities with parlando style of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, a copy of which he had been given by his earliest harmony teacher. The bottom three voices are somewhat static, accompanying the sopranos, who sing a melody which is chant-like in character, though exhibiting a far more extreme tessitura. The homophonic texture is reminiscent of fauxbourdon, a technique of musical harmonization utilized in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Harmonically, the work alternates between tonal and modal tendencies, and doesn’t shy away from atonality; its static chromaticism lends the work a muted, but fervent, devotional quality, beautifully expressive of its text:

O sacred banquet!

in which Christ is received,

the memory of his Passion is renewed,

the mind is filled with grace,

and a pledge of future glory to us is given.

Alleluia.

Messiaen was a synesthete: he experienced the sounds of music in terms of color. Without attempting to ascribe certain colors to specific emotions, he makes harmonic choices which render his music inexplicably “colorful”—a sensation experienced by anyone who listens to this fascinating and beautiful motet.

That is our concert: Messiaen’s O sacrum convivium!, Requiem by Maurice Duruflé, Ubi caritas, a short motet by the same composer, Komm, Jesu, Komm by J.S. Bach, and Dextera Domine, by César Geoffray. If you are scratching your head, wondering how this group of pieces combines in a single concert, come and hear us! You won’t be disappointed.

Sunday, June 9, 3 PM, at St. Thomas the Apostle Church, 55th Street between Woodlawn and Kimbark Avenues, in Hyde Park. The church has a large parking lot, accessible from Woodlawn Avenue.

An Important Minor Composer

In addition to major works by Duruflé and Bach, Chorale will sing some smaller motets by French composers at our June 9 concert. Among these is Dextera Domini, by César Geoffray (1901-1972).

I first heard Dextera Domini in the late 1980’s, when Rockefeller Chapel sponsored a choir from the University of Minnesota in concert. The group’s conductor, Thomas Lancaster, was noted for his wide-ranging, adventuresome taste in choral repertoire, and this particular concert program was no exception.

In addition to major works by Duruflé and Bach, Chorale will sing some smaller motets by French composers at our June 9 concert. Among these is Dextera Domini, by César Geoffray (1901-1972).

I first heard Dextera Domini in the late 1980’s, when Rockefeller Chapel sponsored a choir from the University of Minnesota in concert. The group’s conductor, Thomas Lancaster, was noted for his wide-ranging, adventuresome taste in choral repertoire, and this particular concert program was no exception. I customarily have a pencil in hand at performances and take notes about the repertoire, and this piece warranted a large star in the margin of the printed program. I later contacted Tom for more information, and found that he had actually visited with Geoffray in France, and had had a long conversation with him, which effectively fills some gaps in published accounts of his life and activities.

Geoffray manifested his musical abilities at an early age, and enrolled at the Lyon Conservatory at the age of thirteen, majoring in violin. He studied with composer Florent Schmitt, who in turn had worked closely with Claude Debussy, and obtained first awards in harmony and counterpoint under him. He later wrote that working with Schmitt formed his compositional and musical technique: clarity of harmony, clarity of melody, polyphony, love of music, "inculcating rigor, accuracy, correctness of writing and a certain elegance of the composition” (In “Cesar Geoffray "by François Jaeger / Editions PIF).

After leaving the Conservatory he lived the demanding life of a jobbing musician—playing, teaching, working as assistant conductor at the Casino de Lyon, and composing light music under a pseudonym for the Casino. He also participated in the founding of a new choir in Lyons, Les Fêtes du Peuple. In 1930, he was invited to join an intentional community of artists, Moly-Sabata, under the leadership of Albert Gleizes, where he remained for ten years. During that time, he was increasingly drawn to choral work, especially for young people. In 1932 he became director of the Lyre Ouvrière Bressane, and in 1936 the assistant director of the Chanteurs de Lyon. In September 1940, he was asked to present some musical entertainment, before and after a talk on Scouting, with forty girls and boys. His success with this performance inspired him to continue with this improvised choir, now called the French Scouting Choir. Geoffray became the National Master of Singing for the Scouts of France from 1942 to 1955. Out of this involvement he founded, at the end of WWII, the popular choral movement, À coeur joie, which became an international movement with more than 450 choirs spread over the French-speaking countries (France, Belgium, Canada, Lebanon, North Africa).

As he states in the preface to one of the collections of music he composed for this organization (over 1,000 original compositions and harmonizations), Geoffray's aim was twofold: pedagogical and social. He wanted to teach children to sing, by a clear and precise method, through a series of choral compositions of graduated difficulty. And he had a sincere social concern: he was convinced that group singing would heal the wounds of the World War by providing children with a positive activity around which they could gather and experience the joy of living.

Dextera Domini is typical of Geoffray’s style at the more sophisticated end of his spectrum. His text:

The right hand of the Lord hath wrought strength; the right hand of the Lord has exalted me. I shall not die, but live, and declare the works of the Lord.

is powerful, positive, and uplifting, and he sets it with very specific vocal and rhythmic gestures which clearly elucidate the words. “Rigor, accuracy, correctness of writing and a certain elegance” aptly describes the experience of this short motet. Geoffray learned Schmitt’s lessons well, and adds his own irrepressible, buoyant spirit to the mix. I am as impressed with this piece now, as when I first heard it.

Life with J.S. Bach

My parents had a record player and a handful of records. One each by Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme. Louis Armstrong, and Judy Garland, plus a couple of Cuban rhumba and cha cha dance albums. Also a boxed set of Guimar Novaes playing Chopin, which had been a Book of the Month Club bonus. When I was in high school, I added a couple of Barbra Streisand records. And that’s it. I listened endlessly to all of these, lying on the living room floor at night, in the dark.

My parents had a record player and a handful of records. One each by Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme, Louis Armstrong, and Judy Garland, plus a couple of Cuban rhumba and cha cha dance albums. Also a boxed set of Guimar Novaes playing Chopin, which had been a Book of the Month Club bonus. When I was in high school, I added a couple of Barbra Streisand records. And that’s it. I listened endlessly to all of these, lying on the living room floor at night, in the dark. I’m sure these performers, and the music they performed, profoundly affected my musical shaping, at least as much as the piano lessons I took and the school and church choirs in which I sang.

My mother helped me to buy my own portable record player when I went to college. I took the family records with me, and started to buy a few of my own at the college book store. Sergio Mendes; Blood, Sweat, and Tears; Simon and Garfunkel. I also ventured into “classical” music-- Kirsten Flagstad, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; and a two-record set of the J.S. Bach motets, sung by an English choir, whose name I never paid attention to and don’t remember. These Bach recordings absolutely blew my mind, as we used to say. I played them repeatedly, for myself, for friends, while I studied, while we sat around my room drinking beer on Friday and Saturday nights. Though I went to a Lutheran College, we did not sing Bach in our choirs-- so these recordings were my formative introduction to Bach’s vocal style and works. Thanks goodness the performances were excellent: they made creases in my brain which I would never be able to erase.

My favorite of the motets was Komm, Jesu, komm, BWV 229. From the very beginning, it appealed to me as a perfectly balanced evocation of world weariness and pain, answered by joyous affirmation, faith and hope. I expect that most college-age students feel a good deal of the former, and it was exaggerated by the events and struggles of that time. The Viet Nam War, the civil rights struggle, the deaths of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, the Kent State killings, formed the matrix of my college years, and I know that I, at least, felt little hope and joy in considering the future. I didn’t know that Bach’s motet was thought to have been composed for a funeral, but I surely felt that my world was preparing to die, and his text, written by Paul Thymich, greatly appealed to me:

Come, Jesus, come,

my body is weary,

my strength wanes more and more,

I long for your peace;

the sour path becomes too difficult for me!

Come, come, I will yield myself to you;

you are the true path, truth and life.

It was quite easy to see, and hear, that each line of text was matched to an appropriate musical idea, and to follow the progression of feeling from the darkness of the opening to the soaring lyricism of the final line. There was nothing abstract or ambiguous about it. This clarity really appealed to me then, and continues to do so, now. The difficulty of the piece is not in understanding it, but in executing it: the writing is so dense and complex, polyphonically, harmonically; the articulation so precise and demanding. The choir really has to be firing on all cylinders, and very sure-footed, to pull this off. Though very short-- the motet lasts about eight and a half minutes—the piece really qualifies as a major work and must be treated so, rehearsed as such, if it is to receive an effective performance.

I count it as my great luck, that I happened upon this piece so early in my life. It has accompanied me, as singer and as conductor, throughout my adult musical career. I have grown through it, and witnessed the impact it has on others. I am grateful to have yet another opportunity to perform it this spring, on Chorale’s June 9 concert.

The Sea We Swim In

As wonderful a piece of music as it is, Duruflé’s Requiem means more to me than the notes on the page would dictate. Music is not just pretty, escapist stuff that exists in a sheltered vacuum; high art, low art, in-between art, it is the very matrix in which we live. It doesn’t just accompany us: it runs in our veins; we swim in it, it sustains us. As I prepare for our coming concert, I relive those events of nine years ago; and I’m sure they live, as well, in the musical choices I will make, this time around.

The two principle works on Chorale’s June 9 concert, Maurice Duruflé’s Requiem and J.S. Bach’s double choir motet, Komm, Jesu, komm, though very different in most respects, are both meditations on death.

The Vichy regime, which governed France during the Nazi occupation during the early 1940’s, commissioned Duruflé to compose a symphonic poem; he chose instead to write a requiem mass, utilizing thematic material from the Gregorian Mass for the Dead. Always a self-critical perfectionist, Duruflé worked on it, very slowly, up to the time of the regime’s collapse, in 1944. After the end of World War II, he once again took it up, completing it in September, 1947. Though not specifically designated as such, it stands as a requiem for the war’s dead, much as Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem memorializes those who died during World War I.

I first encountered the Requiem when I was bass section leader of the Chamber Singers at Holy Name Cathedral, in Chicago. Cardinal John Cody died on April 25, 1982, and our director, Richard Proulx, programmed Duruflé’s requiem mass for the cardinal’s funeral. Few of us were familiar with the work, and we had to prepare it very quickly—the funeral took place on April 30. So I had little time to reflect upon the piece, beyond noticing that it was warm, comforting, and gentle in character, much like the Fauré Requiem, that the vocal writing was gracious and idiomatic—easy on the voice—and that the organ part was fiendishly difficult. I have had many opportunities to return to it in the years since, as chorister, soloist, and conductor, in many and diverse settings, with several different organs and organists. Each time I perform it, I am struck anew by Duruflé’s skill, and craft, in incorporating the plainchant melodic lines with his dramatic, virtuosic organ style, creating a seamless, wholly integrated work, which combines ancient and modern musical elements in such a fearless, compelling manner. And does so with music of extraordinary sensual beauty.

Chorale last performed this work nine years ago, on March 27, 2010. Three hours before our scheduled Wednesday dress rehearsal, I received a telephone call from the police department in Harrisburg, Illinois, informing me that my daughter and two of her close friends, on a spring break bicycle trip, had been struck by a van on a remote road in southern Illinois, and had been airlifted to trauma centers in Evansville, Indiana. My wife and a friend immediately left, by car, for the hospital; I had to stay and run the rehearsal. I had no cell phone at that time, so I gave my wife the phone number of Jacob Karaca, a member of the choir. Halfway through our rehearsal, his phone rang. One of the girls was dead, the other two severely injured; our daughter was in a coma, her life hanging in the balance. And then I returned to our rehearsal of Duruflé’s Requiem, a work which had suddenly taken on new meaning for me. We worked for another half hour, and then I had to stop, as the situation caught up to me. John Gorder, our pastor, came to the church; members of Chorale kicked in to arrange housing, meals, rides to school for our other children; to find me a plane ticket; to take care of our dogs and cats; to arrange a ride to the airport. I went home, and our phone was ringing, almost non-stop, with calls from reporters, family members, friends-- national news services had picked up the story, and news of the girls’ accident was being broadcast all over the country. I flew to Evansville and rushed to the hospital—my wife met me at the front door, and then we spoke with one of the surgeons, who wept as he told us that our daughter’s face had been broken like an eggshell. I was allowed in to see her—her appearance was one of the most shocking things I had seen in my life.

Our daughter pulled through. So did Julia, the second friend. When I was sure Kaia was going to make it, I flew back to Chicago, in time to conduct our Saturday night concert of Duruflé’s Requiem. Our pastor spoke to the audience before we began, telling them that we were dedicating our performance to the memory of Faith Dremmer, the girl who had died. The next morning I attended Faith’s funeral; afterward, I collected our other three children, and a friend, Bill Bennett, drove us back to Evansville, where we waited as Kaia recovered sufficiently to travel back to Chicago.

As wonderful a piece of music as it is, Duruflé’s Requiem means more to me than the notes on the page would dictate. Music is not just pretty, escapist stuff that exists in a sheltered vacuum; high art, low art, in-between art, it is the very matrix in which we live. It doesn’t just accompany us: it runs in our veins; we swim in it, it sustains us. As I prepare for our coming concert, I relive those events of nine years ago; and I’m sure they live, as well, in the musical choices I will make, this time around.

Domes, Bells, and Icons

The major work on Chorale’s upcoming concert is the Vespers portion of Einojuhani Rautavaara’s All-Night Vigil (Vigilia). In Orthodox tradition, the All-Night Vigil is a liturgy including both Vespers and Matins that prepares participants for a major feast day. Rautavaara (1928-2016), perhaps the best-known contemporary Finnish composer, composed Vigilia specifically in memory of St. John the Baptist, who announced the coming of Christ and then was beheaded by Herod, at the behest of Salome. The work was inspired by his visit, as a young boy, to the island monastery of Valamo, in Finland’s Lake Ladoga—an experience that remained in the composer’s mind as an overwhelming vision of domes, bells, and icons. Rautavaara’s stirring music has a raw, visceral, yet euphoric quality that is totally unique in twentieth-century a cappella repertoire.

Rautavaara composed the two sections of Vigilia for separate events, Vespers in 1971 and Matins in 1972, and later combined them into a single concert work. In his foreword to the published score, he writes:

The major work on Chorale’s upcoming concert is the Vespers portion of Einojuhani Rautavaara’s All-Night Vigil (Vigilia). In Orthodox tradition, the All-Night Vigil is a liturgy including both Vespers and Matins that prepares participants for a major feast day. Rautavaara (1928-2016), perhaps the best-known contemporary Finnish composer, composed Vigilia specifically in memory of St. John the Baptist, who announced the coming of Christ and then was beheaded by Herod, at the behest of Salome. The work was inspired by his visit, as a young boy, to the island monastery of Valamo, in Finland’s Lake Ladoga—an experience that remained in the composer’s mind as an overwhelming vision of domes, bells, and icons. Rautavaara’s stirring music has a raw, visceral, yet euphoric quality that is totally unique in twentieth-century a cappella repertoire.

Rautavaara composed the two sections of Vigilia for separate events, Vespers in 1971 and Matins in 1972, and later combined them into a single concert work. In his foreword to the published score, he writes:

“The All-Night Vigil ultimately stems from a vision-inducing childhood visit to the island monastery of Valamo in the middle of Lake Ladoga just before the Winter War in 1939; after that war Valamo no longer belonged to Finland. It seemed to me that the islands floated on air, and more and more colourful domes and towers appeared between the trees. The bells began to ring, the low tolling booms and the shrill tintinnabulation: the world was full of sound and colour. Then the black-bearded monks in their robes, the high vaulted churches, and the saints, kings and angels in icons…These images dazzled my ten-year-old mind and lodged in my sub-conscious, to re-emerge fifteen years later in the piano cycle Icons (Ikonit) and again three decades later when I was commissioned to set the Orthodox divine service, or All-Night Vigil. The archaic, darkly decorative and somehow merrily melancholy holy texts affected me deeply. By coincidence, the date set for the performance was the Festival of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist. The proper texts for that day had unbelievable, naively harsh and mystically profound passages.

“No instruments are used in divine services in the Orthodox church, not even the organ. Because of this, I wanted to use the choir in as varied a way as possible. There are numerous solos, most importantly the opening basso profondo; there are also tenor, soprano and alto [and baritone] soloists appearing singly and in pairs. The choir not only sings but speaks and whispers too. It sings in clusters and glissandi (a traditional feature of the ancient Byzantine liturgy). There is also a ‘pedal bass’ group that frequently sinks to a subterranean low B flat; the liturgical recitation features microintervals, and so on. In fact, this All-Night Vigil is closer in spirit and expression to the ancient and lost world of Byzantine chant than to the newer Russian chant which was not established as the accepted style until the 19th century.

“The patron saint of this All-Night Vigil, St. John the Baptist, is specifically referred to in the dramatic bass solos 0f the Sticheron of Invocation and the Irmosses. The variation technique I have used binds and structures all sections and songs of the work together into a vast mosaic. In the midst stand two figures: St. John the Baptist and the Virgin, Mother of God. They are surrounded by the apostolic congregation and on the periphery—through the mystery of ecumenical unity—by all of Christendom and all of Western culture.”

Chicago Chorale is now in its tenth week of rehearsing this extraordinary, electrifying work. It presents several daunting tasks. First: we work with a Finnish language coach, Johanna Hauki, to learn the Finnish pronunciation, as well as to discover and rehearse the word and phrase accents which determine the piece’s constantly shifting metrical structure. We also have to become familiar with Rautavaara’s wholly personal, compelling harmonic language; and the soloists have to learn to sing in the cracks between the half and whole steps to which they are accustomed. Along the way, we have discovered that the All-Night Vigil is not some difficult oddity, intended to stump performers and listeners alike; rather, it is a strikingly original and unusual piece—I have never heard or sung anything else like it. Rautavaara’s descriptive notes come closer than anything I can conjure up, to suggest the emotional, musical impact of this work on the listener. This dramatically engaging work, in constant motion, achieves, through passages of tender beauty as well as great, tragic power, a grandeur and universality seldom encountered in a purely a cappella work.

The contrast between this work and the others on our program could not be more striking. Each composer has a distinctive, compelling voice—from Arvo Pärt’s eerily motionless tintinabula, to Gunnar Eriksson’s whimsical folksong setting, to the lush neo-romanticism of Ola Gjeilo and Peteris Vasks, to the New Age improvisation of Tõnis Kaumann. One cannot escape the impression that the Baltic region is currently the cradle of some of the most important choral music being composed and performed. You owe it to yourself, to hear this music! Seriously sublime.

The Estonian Influence

Two of the shorter works in our upcoming concert are composed by Estonians: Arvo Pärt (b.1935) and Tõnis Kaumann (b.1971).

One of the most performed and celebrated composers currently working in the field of classical music, Pärt was born during the brief window before World War II, during which Estonia and the other Baltic countries were sovereign nations, before being taken over, first, by the Nazis, and then by the Soviet Union. The Soviet occupation profoundly impacted his musical development—little news and influence from outside the Soviet Union were allowed into Estonia, and Pärt had to make a lot up as he went along, with the help of illegally obtained tapes and scores, and under constant threat of harassment from the Soviet authorities.

Two of the shorter works in our upcoming concert are composed by Estonians: Arvo Pärt (b.1935) and Tõnis Kaumann (b.1971).

One of the most performed and celebrated composers currently working in the field of classical music, Pärt was born during the brief window before World War II, during which Estonia and the other Baltic countries were sovereign nations, before being taken over, first, by the Nazis, and then by the Soviet Union. The Soviet occupation profoundly impacted his musical development—little news and influence from outside the Soviet Union were allowed into Estonia, and Pärt had to make a lot up as he went along, with the help of illegally obtained tapes and scores, and under constant threat of harassment from the Soviet authorities.

His compositions are generally divided into two periods. His early works demonstrate the influence of Russian composers such as Shostakovich and Prokofiev, but he quickly became interested in Schoenberg and serialism, planting himself firmly in the modernist camp. This brought him to the attention of the Soviet establishment, which banned his works; it also proved to be a creative dead-end for him. Shut down by the authorities, Pärt entered a period of compositional silence, having "reached a position of complete despair in which the composition of music appeared to be the most futile of gestures, and he lacked the musical faith and willpower to write even a single note (Paul Hillier)." During this period he immersed himself in early European music, from Gregorian chant through the development of polyphony in the Renaissance. The music that began to emerge after this period—a date generally set at 1976-- was radically different from what had preceded it. Pärt himself describes the music of this period as tintinnabuli —like the ringing of bells. It is characterized by simple harmonies, outlined triads, and pedal tones, with simple rhythms which tend not to change tempo over the course of a composition. The work Chorale will present, Nunc dimittis (2001), is an outstanding example of Pärt’s later, tintinnabuli style. He converted from Lutheranism to Russian Orthodoxy, and became immersed in the mysticism of the latter faith. and began to set Biblical and liturgical texts, with an obvious faith and fervor which once again brought him into conflict with the Soviet regime.

In 1980, after years of struggle over his overt religious and political views, the Soviet regime allowed him to emigrate with his family. He lived first in Vienna, where he took Austrian citizenship, and then relocated to Berlin, in 1981. He returned to Estonia after that country regained its independence, in 1991, and now lives alternately in Berlin and Tallinn.

Pärt’s colleague, Tõnis Kaumann, is one of the best-known of Estonia’s younger composers. Active in several musical genres, Kaumann is also a baritone singer in the professional choral ensemble Vox Clamantis, which has performed and recorded much of Pärt ‘s work. Kaumann’s compositional style is classified as post-modern, and is characterized by a high degree of improvisation, humour and a keen sense of the absurd, while being deeply rooted in Gregorian chant and early polyphony. His musical tastes range from the medieval to post-bebop jazz and Abba. The work Chorale will perform, Ave Maria, displays this broad variety of influences, alternating between fauxbourdon-like passage for the choir, chant sung by tenor and bass soloists, and improvisation by three soprano and alto singers.

Darkness and Light

In planning repertoire for Chorale’s concert of Baltic music, I found the program becoming darker and heavier with each piece I considered. This seems inevitable, when dealing with music from the Scandinavian and Baltic regions: this is the nature of art that is born in a harsh climate of long, cold, dark winters; even music for happy events sounds sad and mournful.

Kaia Gjendine Slålien (1871-1972), a rural Norwegian woman noted for her encyclopedic knowledge of Norway’s native folk music

Two of the pieces on Chorale’s upcoming program have Norwegian roots.

In planning repertoire for Chorale’s concert of Baltic music, I found the program becoming darker and heavier with each piece I considered. This seems inevitable, when dealing with music from the Scandinavian and Baltic regions: this is the nature of art that is born in a harsh climate of long, cold, dark winters; even music for happy events sounds sad and mournful. I thought I needed something to lighten the program’s specific gravity, but nothing presented itself; so I declared my planning done, and put the program away, to concentrate on Christmas music. The repertoire continued to bother me, however, and over Christmas break I replaced one of the darker pieces with something more upbeat.

I chose to program Gjendines bådnlåt, a traditional Norwegian lullaby arranged by Gunnar Eriksson (b.1936), professor of choral conducting at the University of Göteborg, noted for his folksong arrangements and experimentation with choral improvisation. He writes: “This arrangement of Norwegian Lullaby(Gjendines Bådnlåt) was created in 1993, I think, in response to a request from Oslo Kammarkör and their fabulous conductor Grete Pedersen. At this time the choir was turning their attention to the treasure of the great Norwegian folk music. Their vision was for various composers to find a more contemporary approach to the music in new arrangements—to give the song a new costume, so to speak—which would bring the song out in the lime light. I was lucky enough to be one of several chosen composers who answered to the challenge. Soon it became clear to me that it takes courage to approach this wonderful lullaby—so I did the “unthinkable” and dressed my arrangement of this Scandinavian jewel with a bit of a Cuban touch, creating a new perspective on the song. To my delight the choir liked it a lot—and a new turn on an old folk tune was born.”

The “Gjendine” of the title refers to Kaia Gjendine Slålien (1871-1972), a rural Norwegian woman noted for her encyclopedic knowledge of Norway’s native folk music. She is remembered primarily for her relationship with Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg, who adapted many of the songs she sang in his piano music.

Ola Gjeilo (b.1978) is one of the most frequently-performed composers in today’s choral world. Born and raised in Norway, he moved to New York in 2001 to attend the Juilliard School, receiving a master’s degree in composition in 2006. His choral works are frequently compared with those of fellow composers Eric Whitaker and Morten Lauridsen, who share with him a crossover, New Age sensibility based on a melding of classical choral tradition with a love of film scores, popular song, and improvisation. He has said that his primary sources of inspiration are nature and cities; and though many of his texts are conventional, straightforward passages taken from the mass or other liturgical and biblical sources, he often names his works after cities or natural phenomenon which inspired or influenced his composition in the first place.

Chorale will perform SANCTUS: London (2009) on our next concert. Gjeilo writes, “London was composed on a cheap keyboard, for kids basically, that I had borrowed when I lived in London back in 2004. I was studying at the Royal College of music at the time, and was writing the piece on the side, following a commission from the Norwegian choir Uranienborg Vokalensemble. Somehow, that atrocious string pad really inspired me, and I’ve used it ever since, even after I got much more advanced equipment. I guess it’s not always about the quality of the gear.”

Gjeilo’s music is lush, harmonically rich, neo-romantic, large and theatrical in conception; he is no “holy minimalist,” following in the path laid out by Arvo Pärt and John Tavener. Yet one hears echoes of his countryman of a previous generation, Knut Nystedt (1915-2014)-- an inescapable solemnity and seriousness of tone, and a dark, emotionally evocative coloration, which are lacking in the music of his American colleagues, Whitaker and Lauridsen. Nystedt’s most famous motet, O crux, could easily have served as a model for much of London. Gjeilo’s music is easy on the ear, but surprisingly rigorous in form and scope. I become more and more drawn to it as we rehearse the piece. And Chorale enjoys singing it.

Saturday, March 30, 2019 at 8:00 PM

Covenant Presbyterian Church

2012 W. Dickens Avenue, Chicago

Sunday, March 31, 2019 at 3:00 PM

Hyde Park Union Church

5600 S. Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago

Music for the Polar Vortex

Chorale’s current preparation (to be performed March 30 and 31) features a cappella music that spans northern Europe from Norway to Finland and south into the Baltic states—a region which provides a rich treasure trove of repertoire for lovers of modern, progressive choral composition. We will sing the Vespers portion of Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara’s Vigilia; Gjendines bådnlåt, a Norwegian folk song arranged by Swedish composer Gunnar Eriksson; Sanctus, by Ola Gjeilo, a Norwegian composer now residing in the United States; Ave Maria, by Tonis Kaumann, and Nunc dimittis, by Arvo Pärt, both Estonians; and Pater noster, by Latvian composer Pēteris Vasks . With the sole exception of Rautavaara, who died in 2016, these composers are currently active and productive. It is a unique and thrilling experience for Chorale to be involved with music which is so much a part of our own time, and composers who are currently developing their own distinctive styles and voices while influencing one another and setting the course for the future of our art form.

Pēteris Vasks (born 1946), Latvia's most prominent composer, is the son of a Baptist minister, and grew up while Latvia was controlled by the Soviet regime. He studied composition at the State Conservatory in Vilnius in neighboring Lithuania, as he was prevented from doing this in Latvia due to Soviet repressive policy toward Baptists. He started to become known outside Latvia in the 1990s, and now is one of the most influential European contemporary composers.

Chorale’s current preparation (to be performed March 30 and 31) features a cappella music that spans northern Europe from Norway to Finland and south into the Baltic states—a region which provides a rich treasure trove of repertoire for lovers of modern, progressive choral composition. We will sing the Vespers portion of Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara’s Vigilia; Gjendines bådnlåt, a Norwegian folk song arranged by Swedish composer Gunnar Eriksson; Sanctus, by Ola Gjeilo, a Norwegian composer now residing in the United States; Ave Maria, by Tonis Kaumann, and Nunc dimittis, by Arvo Pärt, both Estonians; and Pater noster, by Latvian composer Pēteris Vasks . With the sole exception of Rautavaara, who died in 2016, these composers are currently active and productive. It is a unique and thrilling experience for Chorale to be involved with music which is so much a part of our own time, and composers who are currently developing their own distinctive styles and voices while influencing one another and setting the course for the future of our art form.

Peteris Vasks

Pēteris Vasks (born 1946), Latvia's most prominent composer, is the son of a Baptist minister, and grew up while Latvia was controlled by the Soviet regime. He studied composition at the State Conservatory in Vilnius in neighboring Lithuania, as he was prevented from doing this in Latvia due to Soviet repressive policy toward Baptists. He started to become known outside Latvia in the 1990s, and now is one of the most influential European contemporary composers. While he always felt a strong affinity for sacred music, he didn't feel free to express it through vocal music since it would never have been allowed to be performed under the Communist regime. Since the restoration of Latvian independence in 1991, he has turned his attention more and more to religious texts. Pater noster (1991) is his first sacred piece written in his mature style. Vasks' choral writing links him to the composers who have been described as "holy minimalists," a group whose music, while stylistically diverse, tends to rely on tonal and modal harmonies, is frequently harmonically static or slow-moving and is often linked to plainchant and ancient liturgical traditions.

In an interview reproduced on Youtube, Vasks was asked: “When did you compose the Pater noster and what meaning does its title hold for people today? “

Pēteris Vasks: It was in the eighties when my father, who was a minister, often asked – son, when will you compose „The Lord’s Prayer”? …I answered that I hadn’t matured enough to write it. And so the idea kept being postponed; my father passed away, and only after many years did I finally write Pater noster. That’s why for me the piece has a kind of duality – it is for my own father, and for our common Father. Pater noster is a prayer, and I have always thought that prayer is a spiritual concentration, an act of faith, asking for some guidance in this world where we all are lost. Sacred music and sacred texts were the first musical impressions of my childhood. When I began to study composition I quickly understood a fundamental thing. Namely, that in order to be spiritually free you must write instrumental music or at least something with folkloric texts, because in that political regime sacred music was simply forbidden. It was clear to everyone that if you write sacred music, it will end up at the bottom of your desk drawer and never see the light of day. But at that time for me it was more important to hear a live performance, to gain musical experience. For this reason I wrote almost no vocal music and, of course, even less sacred music. In my opinion writing sacred music is the highest responsibility… If true, deeply felt faith is not inherent in sacred music, if it lacks genuine conviction, then it is especially amoral. When my father encouraged me to do it, I wasn’t capable of experiencing it, for to me many other things seemed far more interesting... And then came the nineties, the regime fell, and an interesting metamorphosis occurred wherein many „court” composers of the previous regime stopped praising the (communist) party and suddenly became believers. Again, in the context where new rules came into play and new conditions encouraged writing of sacred works to the point of being almost a trend, I felt no desire to write something like that...