Big Plans/Big Risks

"Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably themselves will not be realized."

Monday, January 6, marks the real beginning of 2014 for most people. Schools reconvene (or not, given the weather here in the upper Midwest); schedules reassert themselves. We realize we have a lot of work ahead of us, and that we have slacked off during the holidays. Chorale began rehearsing our March 16 concert (Bruckner, Mass in E Minor) before Christmas break, but today still feels like a significant marker for us, the beginning of a new season, a door into the future. At December’s board meeting, we talked of coming projects, and made significant, forward-looking decisions; today, we begin to turn those programs and decisions into reality. Repertoire choices, venues, and soloists; budgets, fund-raising, governance-- all aspects of Chorale’s operations kick into high gear, and not just for the coming months: we throw our nets, and our hopes, ‘way into the future.

I heard just a snippet of a radio program on NPR last week, about Chicago’s special business climate, and about the strategies various entrepreneurs employ to achieve success here. Over and over I heard the word “risk”: acceptable risk, too much risk, too little risk. All the speakers seemed to feel that Chicago is a volatile, even brutal, market, requiring big vision and a very high level of risk—requiring a significant leap, to bridge the chasm between the cautious “here and now,” and future achievement. They seemed to be saying, in fact, that caution is likely to lead to failure, and that a surprising degree of recklessness is necessary just to stay in the game. I wish I had heard more, had more context within which to weigh what I did hear. It seemed important to me.

Chorale began twelve and a half years ago with no money and no concrete plans. What we had was a mission: we wanted to rehearse and perform the very best choral repertoire available to us, and we wanted to develop an audience which would support us. We defined ourselves as “amateur” in the best sense of the word: we did this for love, not for individual monetary gain. We felt that amateurs had a right, even an obligation, to sing great music, and we expected to sing it well. Initially, we risked nothing: we simply wanted to please ourselves and our friends. But “rehearsing and performing the very best choral repertoire” turns out to be no small thing: it demands energy, talent, persistence, ambition. Success changes us-- not all at once, but over time: it raises our standards, fosters expectations, invites comparison, criticism, and competition. Success engenders risk: can we handle this repertoire at a good level? Do we sing this piece or that one? Can the singers tolerate, and enjoy, being pushed harder and harder? Will they show up in September to sing the music I choose in May? Am I capable of conducting the works that interest us? Will listeners enjoy and appreciate the programming? How many tickets do we need to sell? How many posters/programs/postcards do we print? Can we afford the postage? Will we meet important deadlines? Can we afford an orchestra? How good an orchestra do we need? Can we afford appropriate soloists? Will they work for what we can pay? Do we perform at new and different venues-- will we draw crowds? Will the acoustics work? Brochure copy, press releases, blog, program notes-- is the writing clear? Can I defend the things I have written? Do they help?

And to paraphrase Robert Shaw: once we have worked so hard to prepare his nest, will the dove land? Will we touch hearts and minds?

Each advance, each development, represents a risk, or constellation of risks, we deal with daily. Often enough, indeed, I feel nostalgic for our naïve early days, when we were pleased that anything at all worked out. When a dream, a plan, a scheme begins to take shape inside me, my litany of risks pops up, and I almost wish the dream would just go away… imagining that neither I nor the group have the energy, the talent, the resources to be thinking so largely and boldly. It happens, though, that the dream seldom does go away; it may harden into a knot and subside into an uncomfortable dormancy, but I can’t escape it.

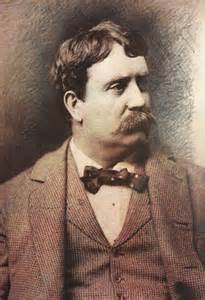

My father admired Chicago architect Daniel Hudson Burnham (1846-1912), and framed a copy of Burnham’s famous creed, which he hung above the toilet in our bathroom. It reads:

Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty. Think big.

Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty. Think big.

My brothers and I memorized this. For good or ill, it has ruled us. Fearful and inadequate though I often feel, I see that it fuels my work and ambitions, regardless of the particular sphere in which I work. Burnham’s words came back to me as I listened to that radio program; and I realized that I ride the horse my father put me on, and have been doing so all along, whether I knew it or not. However humble our building blocks, Chorale “really means it,” is in this for the long haul, and will continue to assert itself, and its vision, with ever-growing insistency.

Lumen de Lumine this Friday and Saturday

As is usual with Chorale, we experience a sudden surge of understanding and competence as we near the concert-- all those weeks seem suddenly to be paying off, and we feel comfortable with, even exhilarated by, the repertoire, and each other.

Only a few days remain, before we present our autumn concert, Lumen de Lumine: Masterpieces of Passion and Faith. As is usual with Chorale, we experience a sudden surge of understanding and competence as we near the concert-- all those weeks seem suddenly to be paying off, and we feel comfortable with, even exhilarated by, the repertoire, and each other. Even those who have sung these works previously—Bach: Jesu, meine Freude; Barber: Agnus Dei; Martin: Mass for Double Chorus—have struggled to relearn them and make sense of them in the context of new voices and new ideas; but we all hear and feel the pieces falling into place, now. By Friday, we will be ready to sing this concert.

I read some novels, especially very difficult and weighty novels, many times. I read Moby Dick about every two years; I have read Bleak House, The Scarlet Letter, Kristen Lavransdatter, Ulysses, The Sound and the Fury, and now Middlemarch, over and over again. I never feel I quite “get” them; I worry about, and mourn, what I have missed, so I go back again, discover how far off the mark I was the previous time, and experience them as new creations. They are, each reading, new stories to me, with new, startling ideas and images. I suspect I don’t have a great memory; I know I don’t have a great intellect. I don’t get bored. I am comfortable hearing the same story over and over again, and letting the discoveries and beauties build up in layers over a long period of time.

I experience music much the same way. If it doesn’t seem worth re-doing, or re-hearing, I don’t give it much time. The more it challenges me, grabbing me with special qualities that stand out and don’t let go, the more intrigued I am—and the more eager I am to give it another try. Really, I have not programmed three “war horses” because I think doing so is good for me, or for Chorale; I program them because they stimulate me, and eat at me, each time I sing or conduct them. I know I am not quite getting them right; I know there is more, just out of reach, but achievable nonetheless; I know that, given another chance, I can do them more justice. And I do have a visceral ache to show them to other people, to share them with other singers—they fill me with a wonder that I am amazingly enthusiastic about sharing.

Yes, each of these works carries with it many personal associations—conductors I have sung them under, singers with whom I have sung them, halls in which I have sung and heard them, singers and students to whom I have taught them, myself. It is undeniably an important aspect of the musical experience, to remember what Robert Shaw looked like at the climax of the Barber, to remember the passion in Helmuth Rilling’s face as he conducted us in the “Weg, weg” section of the Bach, to remember a first, jaw-dropping read-through of the final movement of the Martin with my choir in the loft at Rockefeller Chapel. Such experiences lift the music off the page, and into our very being. More than that, though—I have experienced each of these works as great music, each worthy of that adjective in its own way, but worthy in a lasting, universal sense. The challenges have always been worth the effort; the repetitions have never bored. If I awaken the morning after a concert, wanting to do the whole thing over again and maybe come closer to getting it right, I know I am doing the right thing with the right music.

Jesu, meine Freude

Bach expresses statis, challenge, and growth simultaneously. And he does it with music which pleases and thrills on every level.

J.S. Bach composed all six of his authenticated choral motets between 1723 and 1727, early in his tenure as director of music at St. Thomas’ Church, Leipzig. The majority of his output during these years consisted of church cantatas, composed in a relatively “modern” style, with independent instrumental continuo, obbligato instrumental passages, and movements for solo voice in the operatic style of the period; but he was also required to provide motets (independent choral “anthems” with sacred texts) for ordinary Sunday worship services and special, community events, for which he utilized existing compositions in the sixteenth and seventeenth century style, known as stile antico, as well as his own compositions. These works might have been performed with continuo and doubling instruments, but generally would not have had independent instrumental lines, and indeed could have been (and on occasion may have been) performed with no accompaniment at all. For many years it had been thought that Jesu, meine Freude (BWV 227), the longest and most complex of Bach’s six original motets, was written in 1723 for the funeral of Johanna Maria Käsin, the wife of Leipzig’s postmaster. Recent scholarship discredits this, however, leaving the motet’s purpose and use shrouded in some mystery. Bach scholar Christoph Wolff suggests that it may have been composed for pedagogical purposes, providing Bach with a vehicle for training his students in the vocal techniques and genres required by his extraordinarily demanding cantata repertoire.

Bach composed the first version of his Magnificat, in E-flat major (BWV 243a), for Christmas in 1723. That work utilizes a five-part choral texture, adding a second soprano part to the customary four parts (soprano, alto, tenor, bass), which contributes considerably to the richness of the tonal palette of the work as a whole. It would appear that Bach continued experimenting with this idea in Jesu, meine Freude, augmenting the four-part chorale settings with movements in both five- and three- part textures. This enables him to compose an extended work which maintains the listener’s interest throughout, despite the lack of instruments and solo passages which enriched his more modern cantatas.

Jesu, meine Freude is based on a chorale melody by Johann Crüger (1653), with a text by Johann Franck (c. 1650). The words of the movements 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 are based Romans 8:1–2, 9–11, and speak of Jesus Christ freeing man from sin and death. Franck’s chorale text is written from the believer's point of view, praising the gifts of Jesus Christ and longing for his comfort and strength. Chorale and biblical verses together provide a text rich in stark contrasts between heaven and hell, joy and suffering, frequently within a single section. Bach's brilliant and descriptive word setting heightens these contrasts, resulting in a work with unusually broad dramatic range.

The motet’s structure is wonderfully symmetrical. It utilizes six chorale stanzas, with verses from Romans between each stanza—bringing the total number of movements to eleven. The chorale text by itself doesn’t imply dramatic development; but the biblical interpolations are ordered so that, combined with the chorale texts, they add a certain directional movement: generally, from the general present, to tumult, to the death of earthly concerns, and then to new life and belief, even in the face of continuing strife and sorrow. Movements one and eleven share identical music (a four-part choral setting)—both melodically and harmonically—though their texts differ. Movements two and ten also share similar, though not identical, musical materials; both are five-part, dramatic choruses, utilizing a good deal of dynamic contrast and surprising rhythmic angularity. Movements three and nine return to the chorale melody, but in five-part settings – each, in a different way, elaborating on the melody and harmonic setting familiar to the listener from movement one.

Movements four and eight are scored lightly, for three voices, in the manner of trio sonatas. I suspect that Bach provides a sort of breathing space with each of these, setting contemplative texts set in a manner that allows for calm, thoughtful consideration, without much dramatic coloring. Numbers five and seven, by contrast, are rich, elaborate, highly-charged variations on the chorale melody, set again for five-part chorus; number five in particular sets a very colorful text about standing firm in the face of the very worst that the world can throw at one, and provides the most vivid examples of tone-painting found in the motet. The remaining movement, number six, is a beautifully-structured double fugue, which changes tempo at its climax and concludes with a powerful setting of the text “Now, if any man have not the spirit of Christ, he is none of his.” Movement six, briefly described above, follows immediately on this with the text, “Away! away! Thou art all my delight, Jesus my desire!” as though the speaker, brought to the very brink of hell, pulls himself back just in time, strengthened in his faith and determination. Bach uses a symmetrical, closed structure to describe a developing, strengthening faith—but a faith which comes full circle, back to its source.

Barber's Agnus Dei

Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I'm sure.

At the age of nine, Samuel Barber (1910 –1981) wrote to his mother:

Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don't cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I suppose I will have to tell it now without any nonsense….I was meant to be a composer, and will be I'm sure. I'll ask you one more thing.—Don't ask me to try to forget this unpleasant thing and go play football.—Please—Sometimes I've been worrying about this so much that it makes me mad (not very).

This excerpt tells us two essential things about Barber. First: from early on, he knew himself and what he wanted to accomplish. He had a clear, simple, structurally complete vision of his talent and what he was going to do with it, and was forthright in expressing himself. Second: also from early on, he was prone to melancholy self-reflection, tinged with insecurity and the fear of not being accepted.

Barber was fortunate in his resource-rich childhood. He received the informed encouragement and the backing to follow his intentions. Already by the age of fourteen he was a student at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he studied piano, composition, and voice. The conservatory’s founder, Mary Louise Curtis Bok, took a personal interest in him, and connected him with the Schirmer family, who became his lifelong publishers. At the tender age of eighteen he won the Joseph H. Bearns Prize for his violin sonata, entitled Fortune’s Favorite Child. This seemingly autobiographical work is now lost, perhaps destroyed by Barber himself in later, harder times.

On November 5, 1938, Barber’s Adagio for Strings, arranged from the slow movement of his String Quartet, Opus 11, was performed on a national radio broadcast by the NBC Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Arturo Toscanini, who declared the piece “Semplice e bella” (simple and beautiful). It is difficult for us to imagine, today, the impact this had on Barber’s career. Americans universally regarded Toscanini as the greatest of classical musicians in the European tradition, though exiled from his native Italy by the rise of Fascism, and committed to the United States as his artistic and political home. His public support made Barber an immediate sensation, the most discussed, visible, celebrated composer in America before he was even thirty years old. Toscanini and his orchestra took the work on tour to England and South America, and recorded it in 1942—his first recording of a work by an American. To this day, Adagio for Strings is one of the most recorded works in the classical repertoire.

Toscanini’s support for Barber, and the public’s immediate love of the Adagio for Strings, caused some critical backlash—a backlash which dogged Barber for the rest of his career. Critics faulted Toscanini for promoting a composer whose voice seemed so conservative and so rooted in nineteenth-century European Romanticism, rather than using his influence to champion American composers whose works were more “modern” or more “American.” Ashley Pettis, of the New York Times, wrote that he had “listened in vain for evidence of youthful vigor, freshness or fire, for use of a contemporary idiom (which was characteristic of every composer whose works have withstood the vicissitudes of time). Mr. Barber’s was ‘authentic,’ dull, ‘serious’ music—utterly anachronistic as the utterance of a young man of 28, A.D. 1938!” (November 13, 1938). Barber’s partner, composer Gian Carlo Menotti, responded by wondering if there was room in art for only one way to be modern, and suggested that it might be Barber, not the “modernists,” who was truly progressive by being unafraid to use the models of the tonal masters. He finished his defense of Barber by proclaiming, “It is time for someone to make a reaction against a school of composition that has bored concert audiences for twenty years” (New York Times, November 20, 1938).

The passage of time has demonstrated that Barber refused, as clearly as the most “modern” of his contemporaries, to satisfy expectations. He expressed himself in a personal, direct, inevitable language that happened to be accessible, and based on music from the past. We see in retrospect that he did not choose the easy way, at all; he suffered for his choice, was weakened by depression and alcoholism, and died before critical reappraisal of his works and career caught up with him. Later in the 20th century – in the 1980s and 1990s – a whole wave of composers would turn away from their own “modernist” 20th century idioms to rediscover similar lyrical, spiritual languages. Barber pre-dated them by 50 years; in 1938 he was an avant-garde-anti-avant-gardist (Svend Brown).

Agnus Dei is Barber’s 1967 transcription of the Adagio, for 8-part chorus. The Adagio has from the very beginning been associated in the public imagination with elegiac mourning, nostalgia, love and passion; in transcribing it for voices, with the “Lamb of God” text from the mass, Barber acknowledged and “brought to the surface the work's sense of spirituality”(Graham Olson). His propensity toward melancholy self-reflection, referred to above, is ennobled through this music, and becomes a sort of self-acknowledged cultural melancholia, something we all share and to which we all can relate. Seventy-five years have not in the least dimmed the appeal of this music.

Frank Martin: Mass for Double Chorus

It is amazing to think that Martin refused to let his Mass be published or performed for so long; it is now regarded as one of the masterworks of the twentieth century.

I first encountered Frank Martin’s Mass for Double Chorus in June, 1980. I sang the Kyrie movement with an all-professional church choir here in Chicago, under an ambitious young conductor—and it flopped; fell apart in performance during the church service. I was struck by the music’s beauty and dramatic power, but had no hopes at that time of conducting a choir that could handle it; the failure of these professionals to pull it off deterred further investigation.

Fourteen years later, the Mass appeared on the proposed repertoire list of the Robert Shaw Festival Singers, a group I sang with at the time. Remembering my prior experience with the work, I thought, here is my chance to find out if the work is singable, and worth the effort we would put in to learning it. More than worth it: experience with this piece was one of the top revelations of the years I spent singing for Mr. Shaw. At the end of the festival, following the recording sessions, singers lined up to greet and thank Mr. Shaw; my words were, “Thank you for doing this piece,” to which he responded with a nod, a handshake, and the words, “It is a worthy work, isn’t it.”

Frank Martin was born in Geneva in 1890, and lived until 1974. His ancestors were French Huguenots who left France in the 16th century; his father was a Calvinist minister. Primarily a pianist, he was largely self-taught as a composer, never attending conservatory. After service in World War I, he lived first in Zurich and Rome, later in Paris, where he worked closely on rhythmic theory with Emil Jacques-Dalcroze. At the age of twelve, he was profoundly inspired by a performance of of J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion; years later, he pointed to that concert as the defining musical experience of his life, the cornerstone of his musical foundation. Franck, Ravel, and Debussy also figured prominently in his development.

The years immediately following World War I were a period f extreme ferment and unrest in Western music, and Martin’s own, unusually prolonged development was in fact a synthesis of the many techniques and strains of thought then current. In the early Twenties he composed in a linear, consciously archaic style, reminiscent of fifteenth and sixteenth century sacred vocal music, restricted to modal melodies and perfect triads. Later in the same decade he enriched his harmonic and rhythmic palette through experimentation with Indian and Bulgarian rhythms and folk music. About 1930, he adopted 12-tone serialism as his dominant compositional device, and worked within that framework for the rest of his career.

Martin composed his Mass in 1922, with the exception of the Agnus Dei movement, which he added in 1926, and the work clearly demonstrates the compositional ideas with which he was then grappling. Modeled after the liturgical masses of the Renaissance, with five movements corresponding to the five ordinary sections of the liturgy, it utilizes techniques typical of Josquin and his fifteenth century contemporaries (notice particularly the paired imitation in the Gloria at the words “et in terra pax hominibus,” where the words and melody of one segment of the choir are immediately echoed by another segment of the choir, building toward a grand tutti on the words “glorificamus te”). Large chunks of imitative, almost fugato-like writing, such as that at the very beginning of the Kyrie, suggest the sound and texture characteristic of late sixteenth century composers such as Palestrina and Victoria; the double-choir framework upon which the work is built, particularly in sections such as the Benedictus portion of the Sanctus, and the entire Agnus Dei, where the two choirs are clearly differentiated from and juxtaposed to one anther, hark back to the seventeenth century Venetian style exemplified in the works of Giovanni Gabrieli.

Along with these historically conscious elements, we hear rhythmic and harmonic passages reflecting his interest in more “primitive,” folk, and non-western music. Note particularly, once again in the Benedictus, the percussive effect produced by the second choir, both through an incessant rhythmic pattern and through the use of non-triadic harmonies, particularly open fifths and tritones. Martin demonstrates here his kinship with Stravinsky, whose Rite of Spring was first performed in Paris in 1913.

Traditionally, musical settings of the Mass ordinary were intended for use during worship; through their evolution as a large musical form, mass settings evolved into concert works, typified at their peak of development by such masterpieces as Bach’s Mass in B Minor, which were not suitable for liturgical use. Martin, however, intended his work to function in neither arena; as he wrote in 1970, “I did not at all desire that the work be performed, believing that it would be judged entirely from an aesthetic point of view. I saw it entirely as an affair between God and me…. the expression of religious sentiments, it seems to me, should remain secret and have nothing to do with public opinion.” Martin expresses a Calvinist viewpoint: whereas, for a Roman Catholic, connection with God is achieved through the sacraments, the mass among them, which must be “performed” (in effect, a public act witnessed by more than one person) by a priest (who, through his ordination, is chosen and qualified to intercede between God and humankind), Martin’s relationship with God is private, secret, personal, without intercessor or mediation. A musical setting of the mass, therefore, occupies uneasy territory for Martin: unnecessary as a public liturgical act, its creation, nonetheless, as a product of his own imagination and religious fervor, is a vital act of communication between him and God.

Upon completing his Mass, Martin put it away, never intending that it be heard publicly. He finally allowed it to be performed in 1963, almost forty years after its completion, at the urging of his students. He is on record as considering it a youthful attempt on the way to his mature style; but modern audiences find it richly sonorous and emotionally satisfying.  , and has become a standard work in the repertoires of major choral ensembles.

, and has become a standard work in the repertoires of major choral ensembles.

From Singer to Choral Singer

At Chorale’s most recent rehearsal, our accompanist, Kit Bridges, did something so subtly wonderful during warm-ups that I stopped everything and discussed it with the choir—I wanted them to hear it, pay attention to it, be aware of what he was doing.

At Chorale’s most recent rehearsal, our accompanist, Kit Bridges, did something so subtly wonderful during warm-ups that I stopped everything and discussed it with the choir—I wanted them to hear it, pay attention to it, be aware of what he was doing. It was so small and simple—I asked the choir, in one particular exercise, to begin in the upper register pianissimo, sing down the arpeggio, then crescendo while arpeggiating back to the upper register, ending full forte. They tend to be careless about this, singing the entire exercise about mezzo forte; but Kit, at the piano, played precisely and beautifully what I had asked the choir to sing, and they all copied him. For the first time in twelve years, this exercise worked successfully—because of Kit’s imaginative responsiveness, his understanding of the exercise, and his subtle, behind-the-scenes leadership. I’m not sure even he knew what he was doing—collaboration and responsiveness are second nature to him; I’m not sure the singers even knew they were responding—they simply copied, flexibly and collaboratively. The exercise, which I learned from a former voice teacher of mine, Hermanus Baer, is important, even essential, in building control and flexibility in the upper register—something every singer, and every choir, needs, and something many singers, and choirs, lack. I have no doubt that Chorale will be a better choir, because of Kit’s contribution in this respect, as well as in countless others. As I told the singers at the time: this is why we want Kit to accompany us, rather than just someone who plays the piano. He listens, he responds, he collaborates.

Singers, too, must learn to be more than just singers, if they are to contribute successfully to an ensemble. They have to respect one another, as well as the unity of the ensemble; learn to listen to one another and to the music; they have to adjust their vocal characteristics to the needs of the ensemble, as well as of the music; they have to breathe together, line up their entrances and cut-offs, their vowels and consonants, not only intellectually, but physically, emotionally. They have to live together, musically, to sing together.

With a college-age choir, in a rigorous choral environment, all of this can be encouraged by rehearsing as often as five times a week; by memorizing music; by holding hands during performance; by living together, eating together, cheering together, praying together, dressing alike-- all habits and behaviors which build uniformity of vision and approach. And I have found, in the successful festivals in which I have participated, with Robert Shaw and Helmuth Rilling, a similar intensity of identification, built through constant interaction. In most cases, though, adults, no matter how well trained, talented, and skilled, who sing together only once a week, and lead widely disparate lives outside of rehearsal, will tend just to show up and “sing”-- to regard themselves as singers, rather than as members of a body. Too easily, and pervasively, they do not listen to one another, do not breathe together, do not move and sound as one. This is likely to be true from the most talented and best-paid singers, to the sketchiest of amateurs. They just sing. They are just singers. Too often one hears singers say, relative to a choral performance, “Well, we managed to pull that off! Way under-rehearsed, but we made it through. Thank goodness we are so good, we can get away with this.” And audiences become accustomed to this standard, do not expect more, often don’t even know how much better things could be.

Talent, skill, training, and rigor in the act of singing are very important; but that is only the beginning. Singers, and conductors, have to be aware of this, and develop the disciplines to promote and encourage the rest. Vocal development is a good start: expressing oneself through the medium of an ensemble, which strives to express the vision of a composer, and of a culture, is hugely more than this. Singers have to learn to approach the choral art with integrity and respect-- have to realize that good choral singing is difficult and demanding, and rewarding; by no means something that one falls back on while waiting for a big solo break.

An ensemble is fortunate when a significant number of its members arrive having experienced the choral art on a high level, having internalized the essential standards and disciplines—bring the training and commitment with them, and lead member singers who have not been so fortunate in their backgrounds. Adults haven’t the time or inclination to do all the things a top college choir does, to inspire excellence; but they do better if they remember those experiences, understand their essential value, and constantly reawaken in themselves the collaborative flexibility and high standards these habits have taught them. Kit Bridges doesn’t have to eat, sleep, and pray with the singers he accompanies; his many years of experience have made him supremely responsive to them, while those same years have also made him confident in the choices he makes. This combination of leadership and responsiveness yields high-level collaboration and expressiveness, the goal of any corporate music-making venture.

Chorogenesis

As Chicago Chorale prepares for its first rehearsal of the 2013-14 season, the day after tomorrow, I find it instructive-- and enjoyable-- to look back on our beginnings.

As Chicago Chorale prepares for its first rehearsal of the 2013-14 season, the day after tomorrow, I find it instructive-- and enjoyable-- to look back on our beginnings.

We held our first rehearsal just twelve years ago, on Tuesday night, October 9, 2001, with twenty-one singers present. By the following June, we had grown to twenty-eight members; of those twenty-eight, only four did not have some affiliation with The University of Chicago, and all but six lived in Hyde Park. Auditions were handled by word of mouth: one heard the word, opened ones mouth, and was in. What we shared in common was a love of great choral repertoire, and a desire to sing this repertoire with a group of like-minded individuals. We had no particular strategy for growth and development into the future; we grew as our appetite, reach, and resources allowed and dictated.

We have grown in size; we have experimented with various subsets of the group for specific repertoires; we have tried music from a wide variety of historical periods. Inevitably, we have narrowed our focus, over time, as we have discovered what we are best at, and what our audiences most appreciate hearing. We struggle with these latter considerations: we want to be free to take risks with repertoire and to pull our audience, perhaps kicking and screaming, along with us; and we want to be able to pay our bills. Our geographic and educational base has also grown: only ten of the original group still sing with us, out of sixty members, and only half of those sixty have any affiliation with The University of Chicago. One-third of the singers live in Hyde Park; others commute from as far away as St. Charles, Naperville, Evanston, Flossmoor, and Northern Indiana.

Critic Lawrence Johnson has written of us, “Chicago Chorale is not a high-profile presence on the local music scene with Bruce Tammen’s ensemble only doing two or three programs a year.” He is right about this; we are somewhat ambivalent about how much work we can do, and do well, while continuing to have lives outside of music. We are amateurs: we sing for love, and we earn our living wages elsewhere. But the context of Johnson’s remark is crucial: four lines later, he writes, “Chicago Chorale delivered a glowing, idiomatically Russian and beautifully sung performance. This revelatory and transcendent evening at Hyde Park Union Church was the top performance of 2012.” Though we don’t put a lot of time and effort into raising our profile, and perhaps don’t care so very much about it, we do care, deeply, about the quality and integrity of our work, and about our personal satisfaction in doing that work.

Earlier on, we often discussed the problem with which this stance presents us: how do we justify ourselves, when we ask for money from private donors and corporations—why should they care to fund a group of highly educated culture nerds who seek primarily to please themselves? We don’t worry about this quite so much, now: we have become convinced that audiences enjoy and profit from our hard work, high standards, and self-satisfaction. We have come to believe that our love of what we do, our pleasure in doing it, and our basic faith in the enterprise, is Good—with a capital G—and that our world is enhanced by it. Through these twelve years we have retained this core raison d’etre: we maintain our right, even obligation, to tackle the most important music our there, with the belief that great music, and great singing, is too important to be left to the professionals.

Autmn is almost upon us!

Chorale’s autumn repertoire could be subtitled “core curriculum.” Frank Martin Mass for Double Chorus; Samuel Barber Agnus Dei; J.S. Bach Jesu meine Freude: few serious choral singers will go through life without singing one or more performances of each of these works.

Chorale’s autumn repertoire could be subtitled “core curriculum.” Frank Martin Mass for Double Chorus; Samuel Barber Agnus Dei; J.S. Bach Jesu meine Freude: few serious choral singers will go through life without singing one or more performances of each of these works. One sings them in college and graduate school; one writes papers about them; one hears them on many a concert program. Most conductors and teachers, if asked to designate a “top ten” or “desert island” list, will include one or more of these. And they appeal to non-academic listeners and audiences, as well: they have emotional and rhetorical qualities which reach far past their mapable, describable qualities.

Chorale’s autumn repertoire could be subtitled “core curriculum.” Frank Martin Mass for Double Chorus; Samuel Barber Agnus Dei; J.S. Bach Jesu meine Freude: few serious choral singers will go through life without singing one or more performances of each of these works. One sings them in college and graduate school; one writes papers about them; one hears them on many a concert program. Most conductors and teachers, if asked to designate a “top ten” or “desert island” list, will include one or more of these. And they appeal to non-academic listeners and audiences, as well: they have emotional and rhetorical qualities which reach far past their mapable, describable qualities.

Each work is quite difficult to perform, in its own way. The Martin Mass is thirty minutes of a cappella singing for double chorus (eight parts, divided four plus four), in five movements; each movement has a distinct character, distinct tempos, distinct key relationships, and requires something very different, expressively, from the other four movements. Martin clearly owes a debt to the clarity, the architecture, and the contrapuntalism, of the Roman Catholic church music tradition represented by Palestrina and his contemporaries; but the range—the pitch range of the individual vocal lines; the tremendous distance between high and low volumes; the emotional expressiveness required to satisfy Martin’s vision—is rooted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; it expresses modern artistic trends, and taxes an ensemble’s physical and emotional resources far more than do those earlier models. I first sang this work under Robert Shaw; and his guiding principle was the necessary embrace of this tension between sixteenth and twentieth century styles, neglecting neither; a tremendous feat for a choir to accomplish, and a spellbinding experience for an audience.

Agnus Dei is Barber’s own transcription of Adagio for Strings, his most famous work, for a cappella choir, which sings the music to the Agnus Dei text from the mass. Undoubtedly the most beloved American musical work of the twentieth century. the Adagio has a haunting, elegiac quality which lends itself to great and tragic events, such as the death of John F. Kennedy, and the collapse of the World Trade Center on September 11; and because it is heard so continuously and ubiquitously over radio and television at such times, it has become almost the music of America-- familiar and evocative to people who have no idea what they are hearing. Barber composed the original, for string quartet, when he was very young; his career subsequent to this work was reasonable, but somehow never reached the heights which the success of this work seemed to predict. A personal style so deeply and obviously rooted in the nineteenth century, especially in the music of Brahms, did not appeal to academics and critics during most of Barber’s active career, and this lack of acceptance depressed him deeply, cutting into his potential productivity. Only since his death, seemingly, has the establishment granted him the position in twentieth century music which he deserves; yes, he drew heavily on the past, but his musical energy, drive, and personal vision transcended his roots, giving voice to his individual genius, rather than smothering it.

The Barber, like the Martin, requires extended range, in every respect—pitch, volume, expressivity. The Bach motet, Jesus, meine Freude, requires something very different. One sees, looking at the page, that Bach does not ask so much in these terms: pitch ranges are reasonably narrow, the necessary volume and richness of tone do not exceed anything that can be produced by pre-pubescent boys, and the emotional expression is almost completely communicated through Bach’s writing and text setting. The greatest challenging in singing Bach, is to gracefully sing only what he has written on the page-- intonation, rhythm, melodic line, text presentation; Bach’s genius lies far more in what he has already laid down, than it does in anything the performer adds. His technical requirements are fiendishly difficult—but difficult in small ways: the performer must continually cut back, trimming, narrowing, expressing in a manner that seems almost miniaturist, compared to what one does with the music of Barber and Martin. Intellectual engagement is crucial-- if a performer does not appreciate Bach’s intricacies, his harmonic language, his theology, he cannot present them convincingly. Rodion Shchedrin, the contemporary Russian composer whose Sealed Angel Chorale presented last fall, has said that Bach is 75% mathematics, 25% emotional expressiveness; and all that math can give a performer quite a headache.

So, Chorale has its work cut out. I program these pieces because I am convinced that everyone who ever sings in Chorale, should know them; and that anyone who attends Chorale concerts, should hear them. They are, and should be, our cultural common language—the medium through which we say the best, the most reasonable, the most generous, the most profound things we have to say. The fact that Chorale is a group of amateur singers, gives us all that much more reason to do them-- art this profound should belong to the people, not just to the professionals. It is our patrimony.

The Two Towers at Ravinia, August 15-16

Chorale begins rehearsing tonight, for our performance of The Two Towers with the CSO at Ravinia, August 15 and 16!

Chorale begins rehearsing tonight, for our performance of The Two Towers with the CSO at Ravinia, August 15 and 16! We work two weeks on our own, then join Lakeside Singers and the Chicago Children’s Choir for one joint rehearsal, before getting together with the production’s conductor and mastermind, Ludwig Wicki-- who will put the finishing touches on us, then fit us in with the CSO and the film. The same forces did this two summers ago, for The Fellowship of the Ring-- and we had a great time, attracting the largest audience Ravinia has ever experienced, to view one of the American public’s favorite films.

The musicians fill the pavilion’s stage, as per a usual concert. An enormous movie screen hangs above and behind us; smaller screens hang from trees and poles throughout the park’s grounds. The production team, of which Mr. Wicki is a part, presents all of the film except the music track; the performers on stage perform that live, under Mr. Wicki’s direction. He, in turn, keeps his eyes glued on a laptop which is is right in front of him, on his music stand; he watches a cursor, and exactly matches his gestures to the location of the cursor on his screen, keeping all of us together. Volume levels are controlled from the control booth at the rear of the pavilion, so that the music never overwhelms the dialogue and special effects. The whole thing is an amazing operation. Singers and players must react immediately and confidently to every gesture, though they cannot see the film themselves, or the whole show slides off the road into the ditch. That it never does, is very much to the credit of Mr Wicki’s steel nerves and intense powers of concentration, as well as to the amazing skill and dexterity of the orchestra players, who do not put in anything like the amount of rehearsal, that the singers do.

The singers perform in elvish, orcish, and some kind of early English (at least, it says so in the score instructions!). It all looks like gibberish on the page—written first in some phonetic system particular to the composer, then transliterated into a rough International Phonetic Alphabet, and then tweaked at will throughout the course of rehearsals, according to what we hear on the movie soundtrack—which often follows no rules at all, but sounds good in the given dramatic context. The transliterator/transcriber leaves many questions and issues unresolved—we often plug our noses and jump, during rehearsal, and hope it all turns out OK. Frequently, as well, the singers have to find and sing pitches which may look clear in the piano reduction in our scores, but actually come from the timpani or some other barely pitched or audible instrument, across the orchestra, perhaps while an explosion is occurring on the screen-- and just pray we get it right. I am working from a score used in a previous performance—and frequently see the symbol for a tuning fork, drawn in the score a bar before a choral entrance-- the previous singer was taking no chances.

Many of Chorale’s singers are out of town, or are otherwise unavailable, for this performance; we have filled in our ranks with other singers, drawn from throughout the city, many of them fans of the Tolkien trilogy, who want to have this chance to participate. So the overall experience of learning and performing this score, with a large group of familiar as well as unfamiliar singers, is intensely social, as well as musical, providing a break in routine during the late summer, when it is most needed. And the music isn’t bad, either… Howard Shore, the composer, is skillful both with lyrical beauty, and with large effects, and his music is a surprisingly large part of the movies’ success.

Many of Chorale’s singers are out of town, or are otherwise unavailable, for this performance; we have filled in our ranks with other singers, drawn from throughout the city, many of them fans of the Tolkien trilogy, who want to have this chance to participate. So the overall experience of learning and performing this score, with a large group of familiar as well as unfamiliar singers, is intensely social, as well as musical, providing a break in routine during the late summer, when it is most needed. And the music isn’t bad, either… Howard Shore, the composer, is skillful both with lyrical beauty, and with large effects, and his music is a surprisingly large part of the movies’ success.

Ravinia is a long ways out there. But the trip is doable, by both public and private transportation; and an evening in the park provides a welcome, exhilarating break from the urban routine most of us experience all summer. Bring a picnic! Come see and hear us. August 15 and 16, Ravinia Park, 'way up north near Wisconsin..

Helmuth Rilling retires from position with Oregon Bach Festival

The Oregon Bach Festival, based in Eugene, Oregon, and presented in conjunction with the University of Oregon, recently completed its 44th season-- its final season under founder and artistic director Helmuth Rilling.

The Oregon Bach Festival, based in Eugene, Oregon, and presented in conjunction with the University of Oregon, recently completed its 44th season-- its final season under founder and artistic director Helmuth Rilling. Mr. Rilling’s partner in this amazing undertaking, executive director Royce Saltzman, retired a few years ago, and the Festival has already begun to shift focus and vision under current executive director, John Evans; but this summer marks, effectively, the retirement of their joint stewardship, and the beginning of a new era and direction.

I have participated in the Festival semi-regularly, as a singer, since 1995. Mr. Rilling’s focus on the choral works of J.S. Bach, large and small, was the original impetus for my participation; and I have gained immeasurably through studying and performing these works, some of them repeatedly, over these eighteen years. Helmuth is the real thing: a German Lutheran Kapellmeister, working in a tradition which he inherits from preceding generations, and within which he operates knowledgeably, confidently and imaginatively. On every level, Bach’s church music is Rilling’s native language. English-speaking American musicians, in the thousands, have learned texts, and Bach’s manner of setting them and explicating them, from a man who knows them intimately, and who has deepened his understanding of Bach’s procedures, and genius, through constant study. We learn vocal technique, musicianship, basic performance skills, elsewhere; we learned to put these aspects of our craft at the disposal of Bach’s music, from Helmuth Rilling.

Many of the musicians I know through the festival regularly find themselves in an awkward middle ground with their non-festival colleagues: we are a little too interested in musicology, in why things happen, for our performer colleagues; and we are a little too concerned with practical performance matters, for our musicologist friends. This festival has seemed tailor-made for us. I have been particularly interested in the festival’s pedagogical basis. Originally founded as a series of master classes, organized by Mr. Saltzman and taught by Mr. Rilling, for music students at the University of Oregon, the festival has grown to be far larger than this, with a multitude of concerts and programs running simultaneously; but it has continued to revolve around these master classes, attended by an international group of conductors of many levels and backgrounds. The classes have continued, up to this summer, to be the philosophical core of the festival. Conducting students study works in depth, and conduct them repeatedly, with professional instrumentalists, choristers, and soloists-- and the performers have the opportunity to watch them work, come to understand the issues they confront, and learn the works in greater depth, ourselves. These master classes have unquestionably been the center of the festival for me, and I have volunteered to participate in them at every possible opportunity, at all levels. I feel that we saw Mr. Rilling at his very finest, in this more intimate forum. The major, public concerts were very important, of course, bringing in audiences and participants to experience the large, concerted works; but I lived for the master classes.

Royce Saltzman had the vision, the energy, the administrative ability, the local connections, to found this festival in an out-of–the-way place, and make it thrive, against all logic; Helmuth had the personal charisma, the ingratiating personality, the talent, and the unflagging will, to occupy the space Royce created for him, and to fill it completely. Both men have my undying admiration and gratitude. The festival’s new artistic director, Matthew Halls, along with executive director John Evans, are well on their way to building a new and very valuable program on this original basis, and I look forward to seeing what they do in the future; but I regard myself as very fortunate to have participated so fully in the Rilling/Saltzman creation.

Royce Saltzman had the vision, the energy, the administrative ability, the local connections, to found this festival in an out-of–the-way place, and make it thrive, against all logic; Helmuth had the personal charisma, the ingratiating personality, the talent, and the unflagging will, to occupy the space Royce created for him, and to fill it completely. Both men have my undying admiration and gratitude. The festival’s new artistic director, Matthew Halls, along with executive director John Evans, are well on their way to building a new and very valuable program on this original basis, and I look forward to seeing what they do in the future; but I regard myself as very fortunate to have participated so fully in the Rilling/Saltzman creation.

Announcing Chorale's 2013-14 season

Chorale’s concert programs for the 2013-14 season will begin with the canonic, high-art, sacred repertoire our audiences expect from us, and end with our first-ever concert of entirely secular music. It’ll be a wild ride!

Chorale’s concert programs for the 2013-14 season will begin with the canonic, high-art, sacred repertoire our audiences expect from us, and end with our first-ever concert of entirely secular music. It’ll be a wild ride!

Friday, November 22, 8:00 p.m., will find us in a new concert venue: Augustana Chapel at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, in Hyde Park. Our program will pair two of the twentieth century’s most celebrated works, Frank Martin’s Mass for Double Chorus and Samuel Barber’s Agnus Dei, with an appropriately Lutheran motet, J.S. Bach’s Jesu, meine Freude. These compositions appear frequently enough on the programs of Chicago-area choral ensembles, that they should not be surprising or unexpected; Chorale’s challenge is to breathe new life into them, to conquer the mountains, valleys, and deserts of their technical challenges and then explore the special aspects of each, the extraordinary emotional and dramatic qualities, the structural perfections, which have earned them their positions at the very top of the choral canon. We feel strongly that everyone should know these works, hear them again and again with increasing recognition and appreciation.

We will present this concert twice; the second performance will take place Saturday, November 23, 8:00 p.m., at St. Vincent De Paul Parish, in Lincoln Park.

Each December, a small group of singers from Chorale participates in an Advent Vespers service at the Benetictine Monastery of the Holy Cross, in Bridgeport. We prepare specifically liturgical music, composed for the Office of Vespers by great composers of the Renaissance period, which we alternate with the chanting of the monastery’s monks. This year, on Sunday, December 8, at 5 p,m., we will sing music by Orlando di Lasso. This is an unusual and very beautiful celebration of the Advent season, and one which has been important and meaningful to Chorale’s singers and constituency since we began doing it, twelve years ago.

Chorale’s March 16 concert, 3:00 p.m., at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, will focus exclusively on German music of the Romantic period. The centerpiece of the program will be Anton Bruckner’s monumental Mass #2 in E Minor, for eight-voiced choir and wind orchestra. A massive work, featuring some of Bruckner’s most lyrical, as well as most dramatic, music, it presents challenges which prevent it’s being heard as often as it deserves. Chorale’s presentation of this work will be preceded by performances of a cappella motets by Felix Mendelssohn (Heilig; Herr, nun lässest Du Deinen Diener), Johannes Brahms (Es ist das Heil, Ich aber bin elend), and Bruckner himself (Os justi, Christus factus est). Each motet is a small masterpiece on its own, displaying its composer’s genius as much as any of the larger works for which these masters are revered; presented in conjunction with the Mass, they should contribute to a concert experience of unmatched beauty, in a venue suited to the lofty ideals of German Romanticism.

Our May 18, 2:00 p.m. concert will break ground in many respects. This will be Chorale’s first appearance in The University of Chicago’s Logan Center—and first performance on a concert stage, rather than in a church chancel. In honor of this secular space and its outstanding pianos, and of the freshness of the season, we will present both sets of Johannes Brahms’ Liebeslieder Waltzes, along with other works celebrating spring and love: Francs Poulenc’s Les Chemins de l’Amour, with soprano Tambra Black; Edvard Grieg’s Våren (sung in Nynorsk, no less); Ralph Vaughan Williams’ arrangement of the Scottish folksong Ca’ the Yowes; and Jerome Kern’s All the Things You Are, performed in the original version from his musical Very Warm for May. The many solos in all these pieces will provide Chorale’s fine singers with opportunities to show what they can do outside of a choral context; Kit Bridges will be featured as pianist.

2013-14 will be a reach for Chorale—but a happy reach, featuring music of unimpeachable quality, presented in outstanding venues, performed to Chorale’s usual high standards, with outstanding soloists and instrumental ensembles. How about purchasing a subscription this year, and joining us for all three concerts? I'm sure you’ll be glad you did!

Gardening Notes

I am as passionate about my garden, as I am about anything else in my life and experience.

I garden in Hyde Park, Chicago’s shady South Side enclave. I believe that the impulse—need—to grow things and care for them, is an inherited trait; and I inherit powerfully on both sides. Both of my families grow flowers, vegetables, and fruits, back in Minnesota, my home state, and I grew up in a strongly agricultural milieu; so I brought quite a lot of gardening experience with me when I moved here.

Chicago soil is nothing like the soils back home. Those soils were “natural”: whether beneath the tall grass prairie of my father’s home in west-central Minnesota, or left after the clearing of the deciduous forests in the eastern portion of the state, where my mother’s family lived, they had predictable characteristics, and were uniform over wide areas. One knew what grew well in them, and what did not; one dealt with a somewhat standard growing season, normal precipitation, predictable weather events, common pests; one suffered along with ones neighbors, when disasters occurred. Minnesota is by no means the best place in the country to garden; many other regions have richer soil, better weather, longer growing seasons. But it is gardenable, if one knows the rules. Chicago soil, on the other hand, is anything but natural: with a base of marsh and sand dune, it has endured 150 years of soil, water, and air pollution of the most egregious kind, which has left us with soil conditions that are detrimental, even toxic, to many plants. It fosters the growth of organisms we do not want, and stunts, even kills, plants we would prefer to have. Industrial waste, construction refuse, automobile exhaust, acid rain-- you name it, we have it. Widely spread, and in intensely toxic pockets. The fact that anything at all grows, is testament to nature’s regenerative powers. I suspect one could accurately describe almost any garden soil in the world, as being one of two types: urban, and non-urban.

The major portion of my garden is a strip of land about four feet wide and ninety feet long, bordering an east-west alley, facing south. It has nearly full sun, all day, and easy water access. When I first tackled it, nine years ago, it was a dumping site for refuse from construction of a nearby building—full of concrete chunks, rebar, old bricks, broken glass, sand and gravel; with volunteer trees and weeds—Chinese elm, mulberry, ailanthus, nightshade, poke weed, the usual urban volunteers—growing wherever they could put down roots. Cars and trucks had driven and parked repeatedly on portions of it, packing it hard as rock. I cleared about twenty feet of this plot per year, grubbing out the trees and concrete, disposing of the refuse, loosening as well as I could what was left. I have collected and composted untold amounts of grass clippings and leaves from the neighborhood; horse manure from the nearby police stables; kitchen scraps; used coffee grounds from local coffee shops; shredded paper: anything at all with which I could build the soil. And the job is never done: I still collect all of these items, every season of every year, and am amazed at how rapidly they disappear. The poor, sandy soil at the base of the garden is very hungry, and so are the plants that grow there. A commonly practiced technique is—build raised beds, with a barrier on the bottom, and fill them with new, fresh soil, separate from that which is local. I haven’t done this; I have been committed, from the very beginning, to building the soil that is already present, amending it with local materials; I have never discarded any of the soil, nor replaced it with bags, or truckloads, of imported topsoil.

The garden is basically successful—and is so much better than the alternative. The flowers, from early spring to late fall, are beautiful, and attract pollinators for the fruits and the vegetables. The raspberries and sour cherries are disease-free and bear loads of fruit; we get plenty of tomatoes, beans, peas, potatoes, garlic, onions. Peppers and eggplant have a difficult time: in some locations more than others, they are chlorotic, cannot absorb sufficient nitrogen for good growth, and are stunted. Each urban garden I have planted, has had this problem—as though pockets of past abuse persist in the soil. None of our produce tastes or looks as good as I think it should, is as sweet or colorful or large, as the same stuff grown in rural America: somehow, the soil is not rich and clean and lively enough, the air not pure enough, the beneficial insects not numerous enough. Our neighbors and random passersby, though, are always impressed and complimentary. It is obvious that I work very hard, and have skill and experience; I am gratified by their interest, and grateful for their praise. But I could not sell my produce to high-end restaurants.

So—what if a person, or an agency, offered me a million dollars to upgrade-- to get a backhoe in there, dig out the old sandy soil full of toxins and mysterious objects, build segregated raised beds, bring in truckload after truckload of great soil—effectively, turn professional, adopting the best practices of the successful organic fruit and vegetable producers who sell to places like Whole Foods. It would not have to be on a larger scale than what I do now; but it would be so much easier! and the produce, theoretically, would be tastier, better-looking and more uniform, predictable, competitive. I do wonder about this—often. Are my loving idealism and hard work, largely wasted effort? Fueled by poverty and stubbornness? Is there anything intrinsically or particularly good about this garden, and the process behind it—or do I fool myself, only to be slapped in the face when I am reminded of the real thing.

The thing is-- and this is paramount-- I love my garden. It is the fruit of my best efforts, of my energy and imagination and passion. Often enough, I make mistakes, and the garden saves me-- soil wants to produce, in the worst way, and it finds its own solutions, when I am stuck. We are partners, this garden and I-- in some fundamental though inexpressible way, our relationship models salvation, regeneration, a path through the trouble and turmoil that each of us experiences. To rip it all out and plant new, isolated, unrelated soil, would undo what we learn from one another.

In the meantime—no such money or opportunity appears, so I will continue as I have been doing. Like the garden itself—it is so much better than the alternative.

Auditions for Season 2013-14!

What sort of singer does Chorale want?

Chorale is currently in the thick of new singer auditions for the 2013-14 season. As usual, we have openings in all four sections; also as usual, we have fewer openings for tenors and sopranos, than we have for lowers voices. Chorale tends to have outstanding, and stable, tenor and soprano sections; we have more turnover in alto and bass. Numerous explanations come to mind, none of them really believable or sufficient, for this imbalance; it probably has something to do with the way I behave toward these sections. Weston Noble once told me—when you don’t understand why something is happening/going wrong, look at yourself, first. He was usually right.

What sort of singer does Chorale want?

We want singers with excellent pitch memory and interval recognition, and sufficient technique to sing consistently in tune, without distortion or uncontrolled vibrato. We want singers with innate, comfortable rhythmic sense, who feel the rise and fall of the musical phrase and know, confidently, naturally, when to get in, when to get out.

We want singers who are confident enough that they are free to listen to the rest of the choir, rather than focus solely on their own singing. We want them to be able to “listen louder than they sing.”

We want singers who read music fluently—or, lacking that, read it well enough that they can, and will, work out problems on their own, and arrive at rehearsal far enough along that they can keep up with better readers.

Chorale wants singers who have facility with languages—or who, at the very least, will prepare foreign languages painstakingly, on their own, and be able to contribute to the choir’s efforts, rather than be in need of constant correction. Language is the singer’s greatest single gift , the thing that sets the singer apart from the instrumentalist and makes the vocal art special and irreplaceable. Chorale cares a great deal about language.

Chorale wants singers who commit themselves to regular, prompt attendance. Tardiness and spotty attendance really drag a group down, inject an element of disrespect for the music, for the group, for the conductor. Along with this—Chorale wants singers who respect and admire one another, who are happy to work together, to face the same direction, listen to one another, and produce a unified product.

We want singers who are drawn to the music we program—who are moved, challenged, stimulated by great musical literature.

I purposefully leave vocal quality to last. Yes, Chorale want good voices, with interesting color and dynamic possibilities. But we care more about the musician, than about the singer—we want our singers to place their voices at the service of the music, of the composer, of the ensemble, rather than at the service of some abstract standard of vocal production. We want our singers to love their voices; we want them to love music even more.

A Tour Through Our Coming Concert

Chorale’s current a cappella concert preparation features repertoire from diverse sources, reflecting numerous genres.

Chorale’s current a cappella concert preparation features repertoire from diverse sources, reflecting numerous genres. We have chosen pieces composed in the twentieth century, and appropriate to the Monastery of the Holy Cross’s visual and acoustic qualities; beyond this, though, we have exercised considerable latitude in our choices. I attempt to choose pieces which complement one another and build an effective arc for concert performance; I also have chosen pieces which represent Chorale’s history and personal preferences.

Two of our pieces, Poulenc’s Ave Maria, and Pilgrims’ Chorus by Stephen Paulus, started out as opera choruses. Paulus based his 1997 “church opera,” The Three Hermits, on a Tolstoy story about a bishop and the three saintly hermits who enlighten him. Modest in scope and resource requirements, it is notable largely for it’s choral writing. Pilgrims’ Hymn, excerpted from the opera and published separately, has gone viral in the choral world—it was even performed at the funeral of President Ronald Reagan, in 2004. Ave Maria comes to us by a somewhat more complicated route. It was originally sung by soloists and chorus, with minimal orchestral accompaniment, in Act II, scene II of Dialogues of the Carmelites, Poulenc’s 1956 opera about the seizure of a Carmelite monastery in Compiègne in 1794, and the executions of the nuns who lived there. It has subsequently been arranged as an SSAA chorus with piano accompaniment; in Chorale’s version, men’s voices sing the piano part.

Music for the Orthodox rite figures prominently in Chorale’s repertoire. We are singing two settings of Bogoroditse Devo, (Hail, Mary), one by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, one excerpted from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s setting of the All-Night Vigil, a lengthy liturgy intended to be performed during the night prior to a major feast. Igor Stravinsky, though not widely known for his church music, also composed for the Russian Orthodox Church; we will sing his Otche Nash (Our Father). Finnish Othodox composer Einojuhani Rautavaara has also composed a setting of the All-Night Vigil, entitled Vigilia; we will sing a short excerpt from this work, entitled Litanian Ektena.

Chorale performs German music nearly every season, from both the Lutheran and the Roman Catholic traditions. In fact, singers wishing to sing with us are required to sing one piece in German as part of their audition. On this concert we will present music by two World War II-era Lutheran composers: Hugo Distler’s haunting motet Fürwahr, er trug unsere Krankheit auf, and two movements from Johann Nepomuk David’s Deutsche Messe, Sanctus and Agnus Dei. The tenors and basses of the choir will sing the Ave Maria as set by Austrian Catholic composer Franz Biebl—along with Stephen Paulus’ Pilgrims’ Chorus, one of the most celebrated a cappella works of the entire century.

The third “most celebrated” piece on our program is Alleluia, by American composer Randall Thompson. I vividly remember the day Thompson died: Grant Park Chorus was scheduled to sing a concert that evening, and right before show time, our conductor passed out copies of the Alleluia; we sang it, without rehearsal, for the usual Grant Park audience of thousands. Most of us sang from memory, and nearly everyone in the audience knew it, as well; it was that famous a piece. Rounding out our American group, Chorale will sing the Alice Parker/Robert Shaw arrangement of the Sacred Harp hymn, Hark, I Hear the Harps Eternal, both in recognition of these two giants of American choral music, and in acknowledgement of the vast musical resources we have in these collections of early hymnody.

Only three pieces remain to be listed. The first is a real oddity: Komm, süßer Tod. The original is a song for solo voice and continuo by J.S. Bach. Norwegian composer Knut Nystedt has harmonized it for four voices; Chorale’s presentation, utilizing Nystedt’s harmonization, is organized as an exercise in choral improvisation by Swedish composer and arranger Gunnar Eriksson. It requires five conductors, and comes off differently each time it is performed. The second, Benedictio, by Estonian composer Urmas Sisask, is so popular in the Baltic countries that it is sung at outdoor festivals by thousands of singers, as a statement of national identity and pride. The third, the only English piece on our program, is the fifth movement of the Requiem by Herbert Howells, composed in memory of his son Michael. Chorale does not sing much English music; I find the style to be very particular, and difficult for American choirs to achieve. But this Requiem is a great favorite of mine, and of the choir, and we have performed it in its entirety twice.

Often, Chorale presents new and unfamiliar works, with the goal of surprising and edifying our listeners—as well as our singers. There is a lot of worthy music out there, and we look hard for it. But this particular concert is not about that. We expect that nearly everyone in the audience will be familiar with one or more of the works we are presenting, and that some listeners will know almost all of them. We want to give these well-loved works a hearing in an extraordinary acoustic space, where they can sound in their full glory, and where we can experience, again, the reasons they are so well-loved, and so persistent in the repertoire. Please join us! Sunday, May 19, 3 p.m., Monastery of the Holy Cross.

One Hundred Years of A Cappella Choral Music

What IS a cappella music, anyhow?

What IS a cappella music, anyhow?

The term itself is Italian, and means "in the manner of the church," or "in the manner of the chapel." But Google lists many articles which assert that it means “for voices only,” and this is certainly the definition I learned growing up. Musicologists assumed, based upon what they saw in musical scores from the Renaissance period, that church choirs sang without instrumental accompaniment. An implied value judgment accompanied this assumption—pure vocal music, unadorned by the sensual colors and textures of instruments, pleased God more than concerted music did. The college choral program in which I sang, and others like it, accepted this assumption and made the most of it; choirs travel more easily and inexpensively if a tour’s success does not depend upon the quality of the keyboards in the venues along the way, and if choirs do not have to bring their own instruments and people to play them.

When I came to the University of Chicago as a graduate student, and began singing in Howard Mayer Brown’s motet choir, I discovered that a cappella probably had little or nothing to do with accompaniment; instruments doubled, or even selectively replaced, vocal lines in church music by such great a cappella composers as Josquin, Lasso, Palestrina, and Victoria. Howard’s early music performance program included viols, recorders, and other, earlier instruments -- even an early organ. And the performances he organized through the music department, mostly for the benefit of his graduate students and interested antiquarians in the university community, featured these instruments. I was fascinated by the contribution they made to the overall sound and impact of the Renaissance polyphony we performed. This was nothing whatsoever like performances of similar repertoire presented by my college choir.

Howard and other musicologists discovered that the developing, retrospective discipline of musicology in nineteenth century Europe, while fostering a renewed interest in Renaissance polyphony, also fostered ignorance of the manner in which this music had originally been performed. Nineteenth century composers, such as Mendelssohn, Brahms, Reger, and Bruckner, accepted the prevailing belief, and, inspired by the beauty and appeal of the early repertoire, proceeded to compose their own a cappella choral music with the intent that it be performed without instrumental accompaniment. These composers in turn inspired composers throughout Europe and the United States to write in what was actually a new idiom -- an idiom based upon historical misunderstanding. By the twentieth century we have a new musical genre: the a cappella choir, performing a cappella music. Texts, venues, and audience expectations have in many instances left the realm of “church” music, but the term itself persists, denoting simply “for voices only.”

The subgenre of a cappella music which Chorale will present in its spring concerts—settings of sacred Christian texts, sometimes but not necessarily intended for use in worship -- has inspired composers to scale sublime heights, while challenging singers and conductors to develop an ever more exacting degree of technical precision, vocally and chorally. The twentieth century could almost be termed “the era of the a cappella choir”—many composers made their reputations almost exclusively through composing relatively short pieces for virtuosic choirs, often presented in concerts which would survey the wealth of unaccompanied choral music available to singers and listeners. I recall concerts featuring twenty-five to thirty different compositions, and almost as many composers. Audiences would sit through an entire evening, with one intermission, listening knowledgeably and appreciatively. The composers whose music Chorale will perform demand exquisite control of intonation, of vocal color, of verbal diction, rhythmic articulation, and section-wide homogeneity. Singers not only have to sing well, they have to listen well, agree closely with one another, and embrace a corporate artistic vision. The personal latitude allowed an opera singer, for instance, is unthinkable in a good choir; expressivity and vocal idiosyncracy must be uniform across the ensemble. The composers clearly expect no less. Their music is far too difficult to allow for any “freestyle” singing; and it would make little sense to the listener, were harmonic and rhythmic architecture not clearly delineated, and text clearly projected.

Chorale will present music by composers as generally celebrated as Stravinsky, Rachmaninoff, and Poulenc, as well as by composers known only to choral afficionados, such as Distler, Howells, Sandström, and Biebl. We will make reference to a number of different national styles, as well as to a number of distinct religious traditions. All of the music, however, shares an important commonality: it is written by composers of great skill and integrity, who work hard to share the very best they have to offer. We are challenged to do this glorious music justice.

Time's Tyranny

“But wait,” you say, “the concert isn’t until March 24. You still have three weeks!”

“But wait,” you say, “the concert isn’t until March 24. You still have three weeks!”

Yeah, right. We had already chosen to perform the St. John, secured our venue, and begun lining up soloists, by a year ago. Our orchestra contractor, Craig Trompeter, had gotten commitments from key players. Megan Balderston, our managing director, had already fleshed out her grant proposals; choral scores and orchestra parts had been ordered. I was already studying and marking my score; I had ordered representative CDs from Amazon. Three weeks is nothing, in the world of concert preparation.

Three weeks out, we have already sent postcards, done a couple of email blasts, and arranged for radio ads. Our posters are up; we are reposting, in those locations where they have already been covered, or taken down. Stacks of business cards with our concert information on them are appearing in offices, restaurants, stores, and coffee shops. We sent press releases to newspapers and radio stations long ago, to get them into the queue in time for our concert. We have been selling tickets since September; currently, selling tickets is a high priority, for singers and management, both, and consumes us. But we need also to build and set the stage! Write program notes! Lay out, type and duplicate the program booklet. We have presented a public rehearsal/walk-through of the work for our more immediate supporters, and a listening guide is in the works. I have a couple more such talks scheduled in the coming three weeks. We have already been arranged travel and housing for vocal soloists and instrumentalists who are coming in from out of town; inevitably, though, something will go wrong, something will need attention, between now and March 24.