Baltic Tour Concert Details-- maybe you'll be there to here us!

If you happen to be in the neighborhood, please come and hear us!

Wed 8 July KAUNAS Kaunas Basilica 7 PM Thur 9 July VILNIUS St. Kasimir's 7 PM

Sat 11 July RIGA St. Peter's Church 6 PM

Mon 13 July HAPSAALU Hapsaalu Dom 6:30 PM

Tue 14 July TALINN St. John's Church 7 PM

Thur 16 July HELSINKI Church of the Rock 7 PM

Many of our singers have already left, and are travelling through other parts of Europe before gathering in Vilnius. Good for them! They are having a great time, and will be thoroughly over jet lag by the time the rest of us arrive. Excitement is running high, on both sides of the Atlantic. If you happen to be in the neighborhood, please come and hear us!

Excelsior! Onward and Upward

Our musically and emotionally successful Da pacem Domine spring concert now behind us, Chorale faces a busy summer.

Our musically and emotionally successful Da pacem Domine spring concert now behind us, Chorale faces a busy summer. Twenty-seven of our members will travel to the Baltic countries and present performances of the music we sang last week: July 8 in Kaunas, Lithuania

July 9 in Vilnius

July 11 in Riga, Latvia

July 13 in Haapsalu, Estonia

July 14 in Tallinn

July 16 in Helsinki

Few of our number have ever set foot in any of these countries, and anticipation runs high in the group, as well as the prevalence of preparatory study (we are, after all, a group of educated nerds). In the weeks before our departure, we are rehearsing to adapt our sound and interpretation to a smaller group. Then, on Sunday, June 28, at 3 PM, we will present our “kick-off concert” at Monastery of the Holy Cross, 31st and Aberdeen, in Bridgeport. We expect that the leaner sound produced by twenty-seven voices will be particularly beautiful in this acoustically resplendent space, and we urge all of our constituency—friends, our regular audience, current members who are not making the trip, and anyone else who is curious-- to come and cheer us on. Tickets are a very modest $10, available either on line or at the door. Whatever you may have to miss that afternoon, to carve out time to hear us, I promise you won’t be disappointed: the choir, the repertoire, and the space, will blow you away. This concert was made for Monastery of the Holy Cross…

Several of our singers will leave for Europe right after the concert, to do some private travel, visit friends, and overcome jet lag; the rest of us will fly over to meet them on July 6. Most of us will return to Chicago on July 17, and immediately begin preparations for our performance at the Ravinia Festival. This summer, we will sing the choral portion of the musical score to the movie Gladiator, accompanied by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Justin Freer, conductor, on Sunday, August 2, at 7 PM. These events, at which the film is shown, both on a large screen in the pavilion and on other screens around the park’s grounds, while the music is performed live on the pavilion’s stage, have proved to be major draws, attracting enormous, enthusiastic audiences. Chicago Chorale is extremely fortunate to have been chosen, for a fourth time, to participate; it is the summer’s highlight, for many of our singers.

We will announce our 2015-16 season within the next couple of weeks, after all details have been nailed down. As a teaser, I can say now that we will present an Arvo Pärt 80th birthday tribute in late November; Rachmaninoff’s Vespers in mid-March; and music by Joby Talbot and Herbert Howells in early June. Glorious music sung in wonderfully reverberant spaces. Please plan to purchase a subscription this year, if you have not already been in the habit of doing so; you won’t want to miss any of this wonderful music.

The rest of our June 13 program

Chorale has had a good, and rigorous, experience, preparing this concert.

Many American choirs—and their conductors—are head over heels with English choral music, of all historic periods, and with the English choral sound. Much of this music is indeed extraordinarily good, and the English choirs set an enviable performance standard for the rest of the choral world; but beyond an objectively high level of achievement, so very much of the success of this music lies in performance practice, especially in style of pronunciation—the vowels, consonants, whole phrases, are so clearly and characteristically pronounced, with a distinctive public school accent (which is loved by American ears). And this dialect of English then influences the vocal sound produced by its practitioners. Sadly, most American singers have as hard a time with this accent, as they do with French: we can’t quite shake our own version of English—or our own, rather red meat-and-potatoes approach to vocal technique—and end up sounding caricatured, forced, and out of tune, singing in our native language. My own response has been to program English music sparingly, and then only if I like it for something other than its “Englishness.” Chorale’s upcoming concert includes music by four English composers. Two of them, Henry Purcell and Bob Chilcott, I wrote about several weeks ago; that leaves only two others. The first,

Philip Stopford (b.1977), began his musical career as a member of the choir of Westminster Abbey, and is currently the director of the Ecclesium professional choir, which has recorded many CDs of Stopford's original works, and of the smaller Melisma performing ensemble. A church musician by training and experience, he composes primarily settings of traditional Latin and English prayers and hymns. Ave Verum, composed in 2007, was commissioned by St Anne's Cathedral, Belfast , Northern Ireland, while Stopford was serving as choral director there.

The second, John Tavener (1944-2013), was one of the best-known and popular composers of his generation, loosely associated with Henryk Górecki and Arvo Pärt as a “spiritual minimalist. “ He is known primarily for his extensive output of religious choral works, which have been performed all over the world and recorded by hundreds of choirs. Like Pärt, he was an Orthodox Christian,

though he explored other religious traditions, especially Hinduism, Judaism, and Islam. The Lamb, a setting of William Blake’s poem from Songs of Innocence and Experience, was composed for the birthday of his nephew, and premiered by the Choir of King’s College as part of the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols in 1982.

Chorale has had a good, and rigorous, experience, preparing this concert. As expected, they had to sharpen their ears, eyes, and subtler responses, after the preceding two preparations of orchestrally accompanied music by Mozart and Bach; this program of a cappella miniatures requires constant attention to intonation, a more precise calibration of effect, and a more finely-tuned response across the ensemble. There is no accompaniment behind which the singers can hide. Some of the music is more technically accessible than much of what Chorale prepares—but in almost every case, transparency of texture and harmonic straightforwardness requires better vocalism than something painted with a broader brush. We have been challenged! and we look forward to singing for our audience. We hope you’ll join us: Saturday, June 13, 8:00 PM, St. Vincent DePaul Parish, in Lincoln Park.

Eriksson, Olsson, and Rautavaara-- our nod toward the North.

Chorale tends to sing a large amount of music from the Scandinavian and Baltic region of Europe, and really enjoys it.

Chorale will not sing much Scandinavian or Baltic music on its spring concert, nor on its tour of the Baltic countries later in the summer. This is not our norm: we tend to sing a large amount of music from that part of Europe, and really enjoy it. But we assume that audiences in those countries will come to our concerts because they want to hear something new and different, something more typical of an American choir; if they are choral enthusiasts, they are likely to be plenty familiar with music from their own part of the world, already. The choral culture in those countries is highly developed, and tends to express a fierce nationalism-- and I have a feeling it would seem somewhat odd, for us to be singing music which is so personal and political for our listeners. I’d rather listen to them sing it! The regional music we have chosen to sing comes from Sweden and Finland, rather than from the “Baltic countries” of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (with the exception of Arvo Pärt). And the work listed under the authorship of Swede Gunnar Eriksson is not really by him, or even by a Scandinavian. Komm süsser Tod is the result of many minds’ labor, and defies categorization. Originally, it was the first three lines of a song for solo voice and continuo, which J.S. Bach contributed to Georg Christian Schemelli's Musicalisches Gesangbuch (BWV 478) in 1736:

Komm süßer Tod. Komm sel’ge Ruh’. Komm führe mich in Frieden.

Norwegian composer Knut Nystedt (1915-2014) arranged these lines for SATB voices a cappella, as the basis of a larger composition, named Immortal Bach. Gunnar Eriksson, professor of choral conducting at the University of Göteborg, extracted Nystedt’s SATB harmonization, and published it in a collection entitled Kör ad lib, a collection of thirty-three such kernels selected as subjects for choral improvisation. Following Eriksson’s suggestion, Chorale utilizes four principle singers as leaders of their respective sections; the resulting musical experience reflects their individual choices, though the harmonic combinations are anything but predictable.

Otto Olsson (1879-1964) was primarily an organist, and taught counterpoint, harmony, liturgy, and hymnody at the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. Though his preferred idiom was late Romantic, with rich harmonies, wide tessituras, and ardent emotionalism, Olsson’s choral compositions also demonstrate his affinity for Gregorian chant, and an interest in polytonality. Chorale will perform his Latin motet Jesu dulcis memoria, which, though nominally in B flat Major, has alternating sections in D Major, suggesting a modal, folk music background—Edvard Grieg’s footprint in all twentieth century Scandinavian music -- as much as a modern approach to tonality.

Chorale will sing just one short movement from the All-Night Vigil of Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara (b. 1928), Herra Armahda II. In the Orthodox tradition, the All-Night Vigil is a liturgy, including both Vespers and Matins, which prepares participants for a major feast day. Rautavaara, perhaps the best- known contemporary Finnish composer, composed his vigil specifically in memory of St. John the Baptist. His music has a raw, visceral, yet euphoric quality, totally unique in twentieth century a cappella repertoire. Rautavaara responds to what he calls the “unbelievable, naively harsh and mystically profound” texts of this vigil, with music which is strikingly active, varied, pulsating with energy and emotion. This particular movement sets only the words “Lord have mercy,” but serves as an introduction to the composer’s style in the rest of the work.

This spring's early music

We are including a few pieces of earlier music, which suit our size, our sound, and our preferences.

When putting our Da pacem, Domine program together, I did not intend to be dogmatic about chronology or style. Circumstances require that all of our selections be unaccompanied; theme dictates that texts, and mood, be of a contemplative, peaceful nature, suggestive both of sadness and of joy. I considered, too, the general preferences of the singers: after a season heavy on major, orchestrated works, I thought they would welcome something smaller, more intimate, more nuanced. All of this had to be passed through the refining filters of available rehearsal time, vocal and musical resources, and some hopeful guesses about what our audience would appreciate. Not surprisingly, we ended up with a program heavy on twentieth century. We are a large group (sixty singers), and half of us are women. Most choral music composed before the eighteenth century is better served by smaller ensembles staffed with early music specialists, especially counter tenors and women who can sound like boys; most choral music composed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is accompanied by keyboard or other instruments. With notable exceptions, important a cappella choral music took a break during this period, to re-emerge in the twentieth century as a vital, center-stage art form.

Nonetheless, we did include a few pieces of earlier music, which suit our size, our sound, and our preferences.

Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672), the greatest German composer before Bach, studied extensively with Giovanni Gabrieli in Venice (1609-1612), and returned to that city in 1628 to meet and work with Claudio Monteverdi. He learned progressive, polychoral techniques from them, and composed a good deal of music in this grand, elaborate style, for multiple choirs of voices and instruments, as court composer to the Elector of Saxony, in Dresden. The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), however, gradually took its toll on his opportunity to produce such works: the longest and most destructive conflict in European history, it devastated, among other things, the musical infrastructure of Germany, and pushed Schütz toward a simpler, more austere style later in his career. In the forward to his 1648 publication, Geistliche Chormusik, he describes the contents as “sacred choir music with 5, 6, and 7 voices to be used both vocally and instrumentally…the general bass can be used at the same time if liked and wanted but it is not necessary.” The twenty-nine pieces in the collection react to the events of the time with traditional Biblical texts, several of them pleas for peace. Chorale will sing the 5-voice motet, Die mit Tränen Säen, a setting of Psalm 126:5-6—

They that sow in tears shall reap in joy. They go out with weeping, bearing precious seed, and come back in joy, bearing their sheaves.

Schütz expresses the text’s contrasting elements—tears/joy, go out/come back, sow/reap—with remarkable economy of means, juxtaposing long and short phrases, dissonant and consonant harmonies, painfully slow passages with quick, joyous ones, all in a strikingly efficient composition, short and simple enough for the reduced forces with which he was working at the time.

One of the “notable exceptions” referred to above is Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824-1896), who put some of his best efforts into composing choral music. Associated with the Roman Catholic Church throughout his life, Bruckner was able to combine elements of his daring, avant garde symphonic style with the conservative, Gregorian-based music required by the church hierarchy, and produce a body of church music, both a cappella and accompanied, unsurpassed by other composers of his century. Chorale will sing one of his Marian motets, Virga Jesse floruit (1885), which sets a Gradual text from the Feast of the Assumption:

The rod of Jesse hath blossomed: a Virgin hath brought forth one who was both God and man: God hath given back peace to man, reconciling the lowest and the highest to Himself.

Like Schütz, Bruckner skillfully expresses the contrasts in his text-- God/man, lowest/highest—through direct, efficient musical means, especially through the careful notation of dynamic change, from ppp to fff, and the use of a very wide vocal range: from the top soprano note to the lowest bass note spans three and a half octaves.

A generation later than Schütz, Henry Purcell (1659-1695) is celebrated as England’s greatest and best-known native composer, at least up to the twentieth century, despite his short life. Nominally organist of Westminster Abbey, he contributed to all the musical genres available to him, both instrumental and vocal, and is as noted for his secular, theatrical compositions, as for his church anthems. Chorale will sing Hear my prayer, O Lord, which exists only as an incomplete fragment in the library of Cambridge University, though it is thought to form the opening movement of a longer anthem. Only two and a half minutes long, the piece consists of the working-out of only two short motives, each set to a particular line of text from Psalm 104: 1) Hear my prayer, O Lord, and 2) and let my crying come unto Thee. The first is a concise, chant-like phrase consisting of only two pitches; the second, contrasting, phrase consists of a longer, rising chromatic motive. Over the course of only thirty-four measures, utilizing only these two motives, Purcell gradually amplifies the vocal texture, and intensifies the harmonic complexity, until all eight voices combine in an overwhelming, dissonant tone cluster, before resolving in the final cadence.

In the latter years of the twentieth century, a number of composers attempted to “complete” Purcell’s fragment, by composing companion movements, using elements of Purcell’s work but expanding them with modern harmonic and rhythmic procedures. Chorale will sing the

completion composed by British composer and conductor Bob Chilcott (b.1955). Published by Oxford university Press in 2002, OUP’s catalogue describes it as “a technical 'tour de force', meticulously sculpted from the distilled essence of Purcell's original and yet always recognizably Chilcott. The music is involved, passionate, and frequently contrapuntal. This is a beautiful and convincing work imbued with an unsettling melancholy.” There you have it.

The Americans

Chorale’s June concert program will include a cappella pieces by American composers Stephen Paulus, Vincent Persichetti, Jean Berger, Morten Lauridsen, and Abba Yosef Weisgal.

Chorale’s June concert program will include a cappella pieces by American composers Stephen Paulus (1949-2014), Vincent Persichetti (1915-1987), Jean Berger (1909-2002), Morten Lauridsen (b.1943), and Abba Yosef Weisgal (1885-1981).

Abba Weisgal was born in Kikl, Poland, and received his musical training—both as a cantor, and as a composer—first in Breslau, then in Vienna. He served as an officer in the Austrian army during World War I, and then took up cantorial duties in Eibeschitz, Bohemia. He immigrated with his family to the United States in 1921, hoping to become an opera composer. Very soon after his arrival, however, he was engaged as full-time cantor by the Chizuk Amuno congregation in Baltimore, where he remained for more than forty years, utilizing his compositional talent and skills to provide music for conservative and reform worship. His son, Hugo Weisgall (1912-1997), did become a noted opera composer. Sim Sholom is typical of Abba Weisgal’s liturgical works: it combines elements of Eastern European, Ashkenazic Judaism with the reform, German-influenced procedures inherited from such nineteenth-century composers as Salomon Sulzer and Louis Lewandowski.

Morton Lauridsen grew up in Portland, Oregon, in a Danish immigrant family. After graduating from Whitman College, he studied composition at the University of Southern California. Following his graduation in 1967, he joined the faculty at U.S.C., later becoming chair of the composition department. In 1994, he became composer-in-residence for the Los Angeles Master Chorale, conducted at that time by Paul Salamunovich; through this collaboration, his choral works have become widely known and performed; today he is America’s most frequently-performed choral composer. “O Nata Lux” is an a cappella movement from Lux Aeterna, one of seven major vocal cycles Lauridsen has composed. After its premier in 1997, a writer for The Times called it “a classic of new American choral writing” and said “old world structures and new world spirit intertwine in a cunningly written score, at once sensuous and spare.” He utilizes a limited, conservative tonal palette, enlivened by lyrical melodic lines and unusual chord spacings. His music owes a debt to the spiritual minimalist movement, represented by Arvo Pärt and John Tavener, but has an unmistakably American sound—influenced by popular music of the earlier twentieth century.

Vincent Persichetti, a native of Philadephia, was an extraordinarily prolific composer, and the catalogue of his works astonishes with its breadth-- he wrote for piano, organ, wind ensemble, chamber ensemble, big band, symphony orchestra, solo voice, and chorus. He taught theory and composition first at the Philadelphia Conservatory, and later at the Juilliard School, and was editorial director of the Elkan-Vogel publishing house. He was one of the foremost representatives of what has become known as the American academic school of composition, along with William Schumann and Walter Piston. His compositional “voice” is somewhat eclectic-- it is hard to pin down a specific Persichetti sound; rather, he seems to adapt his materials to the instruments or purposes for which his music is intended. His Mass, Opus 84, for unaccompanied voices, commissioned by New York’s Collegiate Chorale in 1960, is a good example of this: based on a Phrygian mode Gregorian chant, it sounds on many ways like a Renaissance a cappella mass, with a nearly constant imitative counterpoint texture of relying on imitative counterpoint as its chief developmental procedure. Most of the Mass has a dark, somewhat cool, detached, introspective sound; the Agnus Dei movement, which Chorale will sing, is, by contrast, ardent and emotionally expressive.

Unlike Persichetti, Jean Berger focused his creative energies almost entirely on vocal and choral music. Like Weisgal, he was originally European—his original name was Arthur Schlossberg, and he was born into Jewish family and grew up in Alsace-Lorraine. He studied musicology at the universities of Vienna and Heidelberg, and received his Ph.D. in 1931. After the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933, he moved to Paris, where he took the French name Jean Berger, and toured widely as a pianist and accompanist. In 1941, he moved to the United States, joined the U.S. Army, and became a citizen. After the war, he held academic positions in musicology at Middlebury College, the University of Illinois, and the University of Colorado. In 1964 he founded the John Sheppard Music Press in Boulder, Colo., and later Denver. As a musicologist, Berger edited several 17th century works and wrote about the Italian composer Giacomo Perti. His compositional output was not enormous; but several of his choral octavos, including The Eyes of All, are among the best-known and most popular American choral works.

Stephen Paulus lived for most of his life in St. Paul, Minnesota, and received both undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of Minnesota. He composed over 450 works for chorus, orchestra, chamber ensemble, opera, solo voice, piano, guitar, organ, and band; and he held Composer in Residence positions with the orchestras of Atlanta, Minnesota, Tucson and Annapolis. He is best known for his choral music and opera, ranging from elaborate multi-part works and operas with extensive choral scenes, to brief anthems and a cappella motets. Chicago Chorale commissioned a work from him in 2007, entitled And Give Us Peace, which we both premiered and recorded. Pilgrims’ Hymn, which was sung at the funerals of Presidents Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford, is a very successful hybrid: though it functions as a motet, is actually a chorus from his “church opera,“ The Three Hermits. In contrast to the other composers on this “American” list, Paulus never held a “day job”: his entire career was focused on composing and publishing his own music.

Centeno and Pärt, composers

I expect our audience will be as pleased to hear us sing these pieces, as the singers are to perform them.

Da pacem Domine, the title of Chorale’s spring concert preparation, is taken from a sixth century Gregorian hymn :

| Da pacem Domine in diebus nostris Quia non est alius Qui pugnet pro nobis Nisi tu Deus noster. | Give peace, o Lord, in our time Because there is no one else Who will fight for us If not You, our God. |

We chose this theme in response to the constant, tragic strife of which we hear every day—in Syria, in Iraq, in Kenya, in Libya, in Nigeria, in Mexico, all over our globe. No matter what we do with our own lives and careers, day to day, in our relatively safe and stable society, we cannot escape such news, the clamor of war and murder and bloodshed: it dominates most what we see on our television and computer screens, hear about on our radios, read about in our magazines and newspapers. So I have chosen music and texts which respond to this shared situation, providing an island of peace, beauty, and hope. I expect our audience will be as pleased to hear us sing these pieces, as the singers are to perform them.

Chorale will begin and end its concert with settings of the Da pacem text. We will open with a setting by contemporary Spanish composer Javier Centeno, commissioned in 2005 for the First International Meeting of Schola Cantorum in Burgos, Spain. It received its premier performance in the square of Burgos Cathedral, at night, sung by more than 1000 children holding a torch or a lit candle.

I discovered the piece by searching for “Da pacem” on YouTube, and found that it struck just the right tone for our concert. Composed in a straightforward, homophonic style, it has a brooding, emotional tone that I find very appealing—though simple in concept, it manages to evoke deep, complex feeling and reflection. I proceeded to contact Mr. Centeno through an internet search. He very obligingly gave us permission to perform his piece, in what I assume will be its first North American performance.

Mr. Centeno is currently professor on the Teaching Faculty of Burgos University as well as the Department chairman of Didactics of Music Expression. He has performed as a tenor all over Spain as well as in France, Italy and England, principly in oratorio and baroque opera. He performs frequently with such ensembles as the Arianna Ensemble, Grupo de Música Antigua de la Universidad de Valladolid, and Fundación Excelentia. He has conducted the choir of the University of Burgos and has lectured on choral conducting and vocal technique.

Our concert’s final group will include another setting of the Da pacem text, this one by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, composed in 2004. Pärt and his music need little introduction or comment from me-- he is the most performed contemporary composer in the world. This setting, composed in Mr. Pärt’s trademark minimalist style, is quite unlike Mr. Centeno’s—rather than the traditional melody and harmonic accompaniment one finds in the latter, it displays the compositional device Pärt has called tintinnabuli, characterized by simple harmonies and single, unadorned notes suggesting triads and reminiscent of ringing bells. Like Centeno’s piece, it is dark, brooding, evocative of far more feeling and experience than its relatively passive texture would suggest.

Da pacem Domine

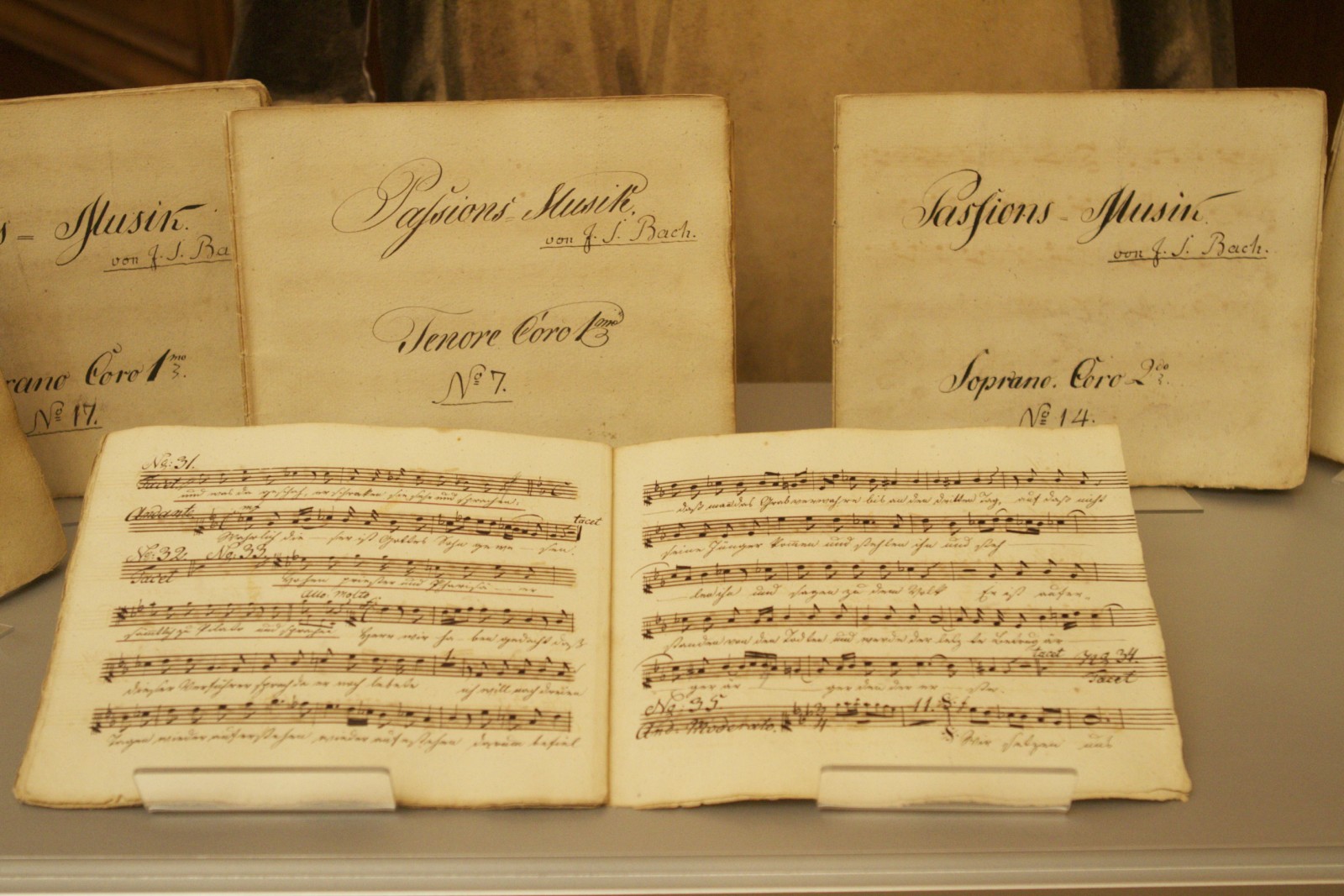

Having laid our St. Matthew Passion to rest, Chorale now moves on to our spring project, Da pacem Domine.

Having laid our St. Matthew Passion to rest, Chorale now moves on to our spring project, Da pacem Domine. This will be a radical departure from the other concerts of our 2014-15 season: whereas both of them consisted of single works, with orchestral accompaniment, presented in grand venues, our current preparation consists of sixteen contemplative a cappella motets, sung in the appropriately intimate, live acoustic of St. Vincent DePaul Parish, in the Lincoln Park neighborhood. I have planned this concert as an opportunity for the singers to work on a genre of repertoire which would challenge them to listen and polish in a somewhat more exacting manner, than they do with accompanied music, which requires larger and more theatrical effects. The a cappella discipline is good for us, and we enjoy the subtle, many-faceted beauty of this music. We also need this time to prepare for our July tour of the Baltic countries, which will be undertaken by a smaller subset of the group, and which by definition requires a cappella repertoire. After the tutti forces sing the program in concert, June 13, that subset will reconvene for three weeks, and prepare the same music as a chamber choir. I have been challenged to select repertoire appropriate to both ensembles-- and in some ways it is the larger group that has the harder job. I am also challenged to select music which will be interesting and satisfying to two very different audiences: our Chicago audience, and the audiences we will sing for in Europe.

One of my guiding principles, in selecting the program, has been to showcase contemporary American composers. I assume this music will be of special interest to European audiences, and I have sought a representative sample—not just because it is American, but because I like it, and because the music and texts fit our theme. We will sing pieces by composers Stephen Paulus, Vincent Persichetti, Jean Berger, Morten Lauridsen, and Yosef Weisgal-- pieces which reflect several different strains of American choral composition, but which share in common a skillful approach to writing for unaccompanied voices. I also chose music from the part of the world in which we will be touring-- pieces by Swedes Gunnar Eriksson and Otto Olsson, Finn Einojuhanni Rautavaara, and Estonian Arvo Pärt. I suspect our European listeners will be familiar with their own music, will be happy with the way in which it is performed “at home,” and will not be as interested in hearing us do it, as they will be to hear us perform our own music—so I have been somewhat sparing in those choices.

I also do not want to limit us to contemporary music for this particular preparation. We will sing a concert of music composed within the past fifty years, based upon the ideas and procedures of “spiritual minimalism,” next season, in honor of Arvo Pärt’s 80th birthday; but for this current program I wanted something looser, with more variety and a broader appeal. Something that might be more familiar and appealing to a general audience (assuming that a general audience is interested in listening to an entire concert of sacred a cappella choral music!). So we will sing motets by Heinrich Schütz, Anton Bruckner, and Henry Purcell, and a chorale by J.S. Bach, all of which fit our theme and are appropriate to our forces.

Our remaining pieces, by Javier Centeno Martin, Philip Stopford, John Tavener, and Bob Chilcott, and not exactly random: they are thematically appropriate and fit the overall sound and tone of the concert, providing colors I feel we need to make a unified whole out of a collection of smaller works.

I’ll write more about our actual theme, Da pacem Domine, next week. For now, though, you should put us on your calendar and plan to attend our concert of extraordinarily lovely music. June 13, 8 PM, St. Vincent De Paul Parish.

Ellen Hargis, soprano, will sing with Chicago Chorale

When Ellen sings with Chorale, soprano members of our group inevitably comment, “I wish I could sing just like that. That is what I would sound like, if I could; and that is just the way Bach should be sung.”

Two years ago, Ellen Hargis sang the soprano solos in Chicago Chorale’s performance of Bach’s St. John Passion. Lawrence Johnson, in Chicago Classical Review, wrote, “Sunday’s performance…benefited from some superb vocal soloists…Ellen Hargis’s clear, expressive singing and bell-like tone in her two arias made one wish the soprano had more to do in this work.“ Well, Ellen is back this season, singing the arias in the St. Matthew Passion; and Bach has granted that wish: she sings in no fewer than eight separate numbers. Her artistry and assured presence enliven all who perform with her— conductor, singers, and instrumentalists; and the audience easily senses the authority and appropriateness of her performance. Music of earlier times, becomes the living music of today, through her committed, gracious, engaged singing.

Chicago is incredibly fortunate to have an artist and teacher of Ellen’s stature living and working right in our midst. She is one of America's premier early music singers, specializing in repertoire ranging from ballads to opera and oratorio. She has worked with many of the foremost period music conductors of the world, including Andrew Parrott, Gustav Leonhardt, Daniel Harding, Paul Goodwin, John Scott, Monica Huggett, Jane Glover, Nicholas Kraemer, Harry Bickett, Simon Preston, Paul Hillier, Craig Smith, and Jeffery Thomas. She has performed with The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, The Virginia Symphony, Washington Choral Arts Society, Long Beach Opera, CBC Radio Orchestra, Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Tragicomedia, The Mozartean Players, Fretwork, the Seattle Baroque Orchestra, Emmanuel Music and the Mark Morris Dance Group.

Two years ago, Ellen Hargis sang the soprano solos in Chicago Chorale’s performance of Bach’s St. John Passion. Lawrence Johnson, in Chicago Classical Review, wrote, “Sunday’s performance…benefited from some superb vocal soloists…Ellen Hargis’s clear, expressive singing and bell-like tone in her two arias made one wish the soprano had more to do in this work.“ Well, Ellen is back this season, singing the arias in the St. Matthew Passion; and Bach has granted that wish: she sings in no fewer than eight separate numbers. Her artistry and assured presence enliven all who perform with her— conductor, singers, and instrumentalists; and the audience easily senses the authority and appropriateness of her performance. Music of earlier times, becomes the living music of today, through her committed, gracious, engaged singing.

Chicago is incredibly fortunate to have an artist and teacher of Ellen’s stature living and working right in our midst. She is one of America's premier early music singers, specializing in repertoire ranging from ballads to opera and oratorio. She has worked with many of the foremost period music conductors of the world, including Andrew Parrott, Gustav Leonhardt, Daniel Harding, Paul Goodwin, John Scott, Monica Huggett, Jane Glover, Nicholas Kraemer, Harry Bickett, Simon Preston, Paul Hillier, Craig Smith, and Jeffery Thomas. She has performed with The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, The Virginia Symphony, Washington Choral Arts Society, Long Beach Opera, CBC Radio Orchestra, Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Tragicomedia, The Mozartean Players, Fretwork, the Seattle Baroque Orchestra, Emmanuel Music and the Mark Morris Dance Group.

Ellen performs at many of the world's leading festivals including the Adelaide Festival (Australia), Utrecht Festival (Holland), Resonanzen Festival (Vienna), Tanglewood, the New Music America Festival, Festival Vancouver, the Berkeley Festival (California), and is a frequent guest at the Boston Early Music Festival.

Her discography embraces repertoire from medieval to contemporary music. She has recently recorded the leading role of Aeglé in Lully's Thésée for CPO, nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording in 2008, as well as Conradi's opera Ariadne, also nominated for a Grammy Award. She is featured on a dozen Harmonia Mundi recordings including a critically acclaimed solo recital disc of music by Jacopo Peri, and in Arvo Pärt's Berlin Mass with Theatre of Voices, and two recital discs with Paul O'Dette on Noyse Productions.

Ellen Hargis teaches voice at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, and is Artist-in-Residence with the Newberry Consort at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. Her local performances with the Newberry Consort, in Hyde Park, Evanston, and downtown, are highlights of the Chicago concert season. Follow this link for more information about the her performances this weekend!

When Ellen sings with Chorale, soprano members of our group inevitably comment, “I wish I could sing just like that. That is what I would sound like, if I could; and that is just the way Bach should be sung.” I invite you to come hear what they mean, March 29, 3 PM, at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel.

The Living Bach

The Matthew Passion awes through its brilliance, genius, monumental achievement. Beyond this, though, it speaks of pity, compassion, love and reverence for all creation. Matthew’s story is the human story, reenacted every day in every corner of our globe.

After three week’s medical hiatus, I am back at this. During those three weeks, I listened almost daily to recordings of Bach’s Matthew Passion; during the third week, I was able to follow along in the score, and actually do some private rehearsing. I had many quiet hours to think about the work, to consider its meaning and relevance for today’s listeners, as well as to marvel at the skill of the performers on these recordings, and try to learn from what they were doing. Art works from the early eighteenth century tend to end up in museums-- or as museums, themselves. We walk through museums, marveling at the incredible skill, art, cleverness of the long dead artists, and of the schools or trends which they represent. We read in visitors’ guides about religious or social movements of the period; we discuss and are at least dimly aware of the iconography which indicates deeper meanings than we see on the surface. But it is all long ago and far away; we don’t paint or sculpt or write that way any more, and most aspiring artists, attempting to define a new, personal identity, would not want to learn how.

Music somehow is different. Even with the high-quality recordings available to us, we require that music sound, and that we musicians of today enable that sounding, actually learn to do what musicians did in the eighteenth century. We put on live performances. Audiences want to hear it live; and we want to perform it live. So we work very, very hard, unlike our colleagues in plastic or verbal arts, to produce museum-quality performances. In the process, we must and do ask ourselves-- Why? Does anyone today believe what Bach was attempting to convince his listeners to believe? We now live in a multicultural, multi-religious, even in many respects nonreligious world; few people, if any, subscribe to the homogeneous religious tenets of 1720s Leipzig. Much of the dogma which served as the underpinnings of Bach’s texts has completely disappeared; some aspects of it have been used to justify acts of barbarism and murder, and deeply disturb modern listeners.

Nonetheless, we continue to school ourselves in the performance of Bach’s music, vocal and instrumental. To a great extent, we do this because it is so good, so monumental, and so gratifying to perform and hear. Few composers yield such rewards. It is a commonplace, worth restating, on which listeners and performers from a wide variety of religions and ethnicities agree: Bach is in a class by himself. His music speaks to us all. But what is it, that it speaks? Certainly, it speaks brilliance, genius, monumental achievement. Beyond this, though, it speaks of pity, compassion, love and reverence for all creation. The Matthew Passion, following the words and characterization of Matthew’s Gospel, shows us Jesus the man-- loving, melancholy, impatient, sorrowful, in great pain, finally and horribly alone in his trial and death. As the soprano soloist sings, ”He has done only good for us all; he has returned to the blind their sight, the lame he has made to walk again; he drove the devils out, he has comforted the mourners, took the sinners to himself. Only these things has he done; otherwise, nothing. Out of love, my savior now is dying.” I suspect there is no one who cannot relate to this figure, who does not weep at the horrible calamity of his death. We understand his disciples, from Judas to Peter, who cannot really believe what is coming, and cannot see their own weakness and failing until it is too late. We understand Pilate, intelligent and insightful but helpless, and we understand the fury of the mob. Matthew’s story is the human story, reenacted every day in every corner of our globe.

Each time I read Moby Dick, it possesses me; each time I have sung Winterreise, I have been owned, lock stock and barrel, by Schubert. Bach’s Matthew Passion exerts the same sort of ownership over me. I find myself at the very intersection of the divine and the mortal, where everything on the page and in the air is holy. I hope you will come and share in the fruits of Chorale’s hard work. March 29, Rockefeller Chapel.

An Urban Oasis - Guest post by Megan Balderston

Bruce has been recovering from eye surgery for the last couple of weeks, and has been necessarily absent from the blog. Therefore, a number of us from the choir will be giving our thoughts on the upcoming concert as he recovers. I expect he will have a new post up in the next week or so, himself. As the sometime-singing managing director of this ensemble, I’m sad to say I will not be taking my place amongst the first sopranos during the Passion. The reason is that I am the de-facto producer of this concert, and there are approximately a million moving parts to it. The St. Matthew Passion is a monumental work. We are splitting into double choir, and children’s choir (ably led by Chorale bass Andrew Sons, photo below), and presenting our wonderful period orchestra, and outstanding soloists, some of whom are flying in specifically for the work. We are building a stage to hold everyone in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, and that is an expensive and occasionally nerve-wracking project. Thank goodness for their Dean, Elizabeth Davenport, and her able staff for their thoughtful and methodical approach to fitting everyone on stage.

There are travel arrangements, rehearsals, communicating with everyone… and all the while working on keeping the general business end of things running. No, it’s probably a good thing that I am on hiatus as a singer. Unfortunately, that means that I cannot explain to you, as a singer, why this work speaks to me. But I can give you a few really great reasons to join us on March 29th as we present the work.

Several years ago I was introduced to a gentleman in my neighborhood who, as one does, asked me what I do for a living. As I was explaining Chicago Chorale, he gripped my arm suddenly and said, “Do you perform the St. Matthew Passion?” He then proceeded to get teary-eyed as he told me how profoundly this work touches him, and made me promise to let him know the moment we programmed it again. In all of my life as a musician and arts administrator, I have never had someone break down while chatting casually about a musical work…and at a cocktail party, no less. I was reminded of this several weeks ago when one of our members told me that she makes her children listen to the recording in the car because “It is so beautiful that it makes me weep, and they need to know that kind of music.”

We have had a tough winter here in Chicago. Don’t you owe it to yourself to have a mini-retreat, right here in town? If you have not yet listened to Bach in the glorious space of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, while the afternoon light streams through the windows, you are missing out. Give yourself an afternoon of reflection and beauty.

Finally, as much as I love listening to recordings, music as glorious as this begs for the tension and drama of live performance. When we get excited by something, we also are vulnerable. Singing this work is opening up our singers’ hearts and minds, and they want to share that with you. We hope we see you at our urban oasis: Rockefeller Memorial Chapel on March 29th.

Angela Young Smucker, Alto Soloist in Chorale's Matthew Passion

Bach intended that these solos be sung by members of the chorus; but they are phenomenally demanding—vocally, musically, emotionally—and require highly-skilled singers who specialize in this particular repertoire, to be sung convincingly.

Four of the singers seen and heard in the St. Matthew Passion are not Biblical characters at all. Rather, the dramatic action of the passion narrative halts, and these singers, functioning as spokespeople for the community of believers, step out from the chorus and deliver soliloquies—settings of contemporary, contemplative poetry--reacting to the actions taking place with personal expressions of fear, sorrow, faith. These soliloquies are set as virtuosic recitatives and da capo arias, in the style of eighteenth century baroque opera. Bach intended that these solos be sung by members of the chorus; but they are phenomenally demanding—vocally, musically, emotionally—and require highly-skilled singers who specialize in this particular repertoire, to be sung convincingly.

Four of the singers seen and heard in the St. Matthew Passion are not Biblical characters at all. Rather, the dramatic action of the passion narrative halts, and these singers, functioning as spokespeople for the community of believers, step out from the chorus and deliver soliloquies—settings of contemporary, contemplative poetry--reacting to the actions taking place with personal expressions of fear, sorrow, faith. These soliloquies are set as virtuosic recitatives and da capo arias, in the style of eighteenth century baroque opera. Bach intended that these solos be sung by members of the chorus; but they are phenomenally demanding—vocally, musically, emotionally—and require highly-skilled singers who specialize in this particular repertoire, to be sung convincingly.

Angela Young Smucker will sing the alto solos in Chicago Chorale’s production of the Passion. Chorale audiences will remember her as the alto soloist in our 2011 performance of Bach’s Mass in B minor. Angela is a Chicago-based singer, known to area audiences largely through her performances with the Haymarket Opera Company, Chicago's 17th and 18th century opera troupe. As a founding member, Ms. Smucker has appeared in productions of Handel’s Acis, Galatea e Polifemo (Galatea) and Clori, Tirsi e Fileno (Fileno); Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (Sorceress); and Charpentier’s Actéon (Hyale).

Highlights of her 2014-15 season include a recital featuring the music of Abraham Lincoln’s life; debut performances with the Chicago Bach Ensemble; performances of Handel’s Messiah with Chicago’s Bella Voce and Callipygian Players as well as the Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra; Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (Parts IV-VI) with the Bach Institute of Valparaiso University; a recital collaboration with Baroque cellist Craig Trompeter; and performances of early Polish music with the Newberry Consort.

As a concert artist, Angela has been recognized for her artistry in the repertoire of J.S. Bach: “Her discerning interpretation of the texts matched her creamy alto sonority and perceptive traversal of Bach’s serpentine vocal lines… Smucker demonstrated how astutely Bach fused such rhetoric into his music” (SanDiego.com). She has performed all of his major works, as well as numerous cantatas, and is a regular soloist with the Bach Collegium San Diego and the Bach Cantata series at Grace Lutheran Church. She has been a featured soloist under the direction of Bach scholars Helmuth Rilling and Hermann Max, and has performed at Leipzig’s St. Thomaskirche with the Leipzig Baroque Orchestra. She was also a Virginia Best Adams Master Class Fellow at the Carmel Bach Festival, has been the alto soloist for the Oregon Bach Festival Discovery Series.

Concert work from past seasons includes Mozart’s Coronation Mass (Music of the Baroque), Mendelssohn’s Elijah (Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Oregon Bach Festival), Haydn’s Creation (Oregon Bach Festival), Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience under the baton of Philip Brunelle, Mozart’s Requiem, Vivaldi’s Gloria, Handel’s Israel in Egypt and Messiah, Duruflé’s Requiem. She has been a featured artist in the U.S. premieres of Robert Kyr’s O Word of Light and Thunder (Evangelist), Francis Grier’s The Passion (Herod), and Siegfried Matthus’ Te Deum (Mezzo Soloist). Angela has also been featured on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion and WFMT’s Impromptu.

Angela’s work as a chamber artist has also earned high praise. Her debut performances with French Baroque ensemble Les Délices were chosen as a 2013 “Cleveland Favorite” by The Plain Dealer. In addition to the Bach Collegium San Diego, Newberry Consort, and Bella Voce, she has worked with Grammy-nominated ensemble Seraphic Fire, as well as the Grammy-winning Conspirare, Chicago Symphony Chorus and Oregon Bach Festival Chorus. Other choral work includes the Grant Park Music Festival Chorus, Chicago A Cappella, VocalEssence Ensemble Singers, Santa Fe Desert Chorale, Heartland Chamber Chorale, and Festival Ensemble Stuttgart.

Where do all those words come from?

A worship community could simply mount a reading of the biblical text, add a few hymns and a couple of meditations spoken by a worship leader, and be done with it. That Bach went so very much further, is his great gift to us.

Bach’s setting of the Passion According to St. Matthew was first heard on Good Friday, April 11, 1727, in Leipzig’s Thomaskirche. We twenty-first century listeners and performers must always remind ourselves that this presentation was not a concert: it was a liturgical expansion of the Vespers service, designed to recount the story of the final days of Jesus’ life, as told in chapters 26 and 27 of the Gospel of Matthew the Evangelist (in the 200-year old German translation by Martin Luther), in a manner which would make it comprehensible and meaningful to the Lutheran citizens of Leipzig. Besides the Biblical narrative, Bach set contemporary German poetry, written, adapted, and arranged by his friend and contemporary Picander (pseudonym of poet Christian Friedrich Henrici, 1700-

1764), which functioned as meditations on the Biblical text, and was intended to clarify the meaning of the story, and the motivations and reactions of the characters in the narrative, for the listeners. Presumably these meditations were to guide the understanding and private devotions of the listeners—and in this light, both Picander and Bach served the community as theologians and worship leaders. A third category of text utilized by Bach and Picander is the large number of chorale verses from the Lutheran hymnal, already well known to the listeners.

Bach sets the Biblical text largely in recitative, both secco and accompanied, in a style already familiar to his listeners from opera, especially the operas of Georg Philipp Telemann, who served as musical director for the short-lived Leipzig Opera, 1703-05. The most prominent presenter of this text, of course, is the Evangelist himself, sung by a tenor soloist; but other characters are featured as well, including Pilate, Pilate’s wife, Peter, Judas, the High Priest, a couple of maids, some witnesses testifying at Jesus’ trial—all of them sung by soloists from the ranks of the choir. The choir, sometimes as a single unit, sometimes in two opposed and conversing groups, presents the words of the disciples, the Roman centurions, the priests, and the angry crowd. These crowd scenes, called turba choruses, are not set as recitative, but rather as complex, difficult choral interjections, composed and performed with a character and style suggestive of the scene they portray.

The settings of contemporary poetry are also composed in operatic style, often as paired recitatives and arias, and usually featuring virtuosic writing for principle instruments from both orchestras. Though the actual performers are often the same singers who portray named characters in the biblical sections-- in Bach’s original conception, for instance, the tenor who sings the arias also sings the Evangelist-- these recitatives and arias are meant to be heard as the thoughts and feelings of community members, of observers, in response to

the Biblical narrative. It seems that, in Bach’s own performances, chorus members stepped forward and sang these texts, whereas the words of Peter, Judas, and, perhaps, some others, were sung by singers who were not “community members.” This practice has not, however, been followed since Bach’s own time; the arias are so demanding that specially trained soloists are engaged to sing them. Bach also composes “choral arias”: major movements which set contemplative poetry, sung by the combined vocal forces rather than by soloists.

The chorales, both music and texts, were very familiar to Bach’s listeners. Bach and Picander selected both melodies and verses carefully, to reflect the actions and attitudes being presented in their telling of the story-- so these movements have the dual role of providing comfort and familiarity to the listeners, and introducing yet more reinforcement for the overall themes of the Passion presentation. I have participated in Passion performances in which these movements were actually sung by the audience; but there is no evidence that Bach actually intended this. In some movements, Bach combines chorales, sung by the choir, with arias, sung by soloists—a hybrid procedure which functions on several interlocking levels in the telling of the story.

Odd to think about the words being more important than in the music, especially the music of Bach; but this seems to have been Bach’s own attitude and intent, in his liturgical works: to use music as a means for presenting essential text in the most immediate, dramatic, and comprehensible manner. A worship community could simply mount a reading of the biblical text, add a few hymns and a couple of meditations spoken by a worship leader, and be done with it. This is common practice in many Christian churches on Good Friday, even today. That Bach went so very much further, is his great gift to us.

Why did Bach compose his Passion According to St. Matthew?

The scope of Bach's contributions to the genre was, and is, exceptional, but the fact that he composed and mounted these productions is not: he was expected to organize some version of a passion reading, in his position as cantor of Leipzig.

In the Christian tradition, the “Passion” is the narrative, common to the four gospels, recounting Jesus’ suffering – physical and spiritual-- between the night of the Last Supper, and his crucifixion, the following day. The word itself is based upon the Latin noun passio: suffering; and shares this root with our word “patience.” Christians commemorate the Passion during Holy Week, which begins on Palm Sunday and ends the following Saturday at midnight. Following a tradition dating back to the 4th century, most Christian denominations read one or more narratives of the Passion during Holy Week, especially on Good Friday. In some congregations, these readings are communal, with one person reading the part of Christ, another reading the descriptive narrative, others reading various smaller characters, and either the choir or the congregation reading the parts of crowds and other bystanders. People began to intone (rather than simply speak) the Biblical Passion texts at least as early as the 8th century. This chanting of the text may have been freely interpretive in the beginning, but within two hundred years manuscripts began to specify exact notes to be sung. By the 13th century different singers performed specific characters in the narrative (as in the communal readings described above), a practice which became fairly universal by the 15th century, when polyphonic settings of the crowd scenes began to appear, also. By the 16th century, Passion settings had evolved into a highly developed genre, with a number of different sub-genres, composed by the prominent composers of the time. Martin Luther disapproved of the entire genre, writing, “The Passion of Christ should not be acted out in words and pretense, but in real life.” Nonetheless, sung Passion performances were common in Lutheran churches right from the beginning of the Reformation period (1517), in both Latin and German, and by the 17th century had evolved into the “oratorio passion” sub-genre, heavily influenced by the development of opera, which included instrumental accompaniment, interpolated texts, other Scripture passages, Latin motets, chorales, arias, and recitatives.

J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew and St. John Passions are the best known of this latter type. The incredible scope of his contributions to the genre was, and is, exceptional, but the fact that he composed and mounted these productions is not: certainly he was expected to organize some version of a passion reading, in his position as cantor of Leipzig. The form continued to be very popular in Germany throughout the 18th century—Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, composed over twenty settings. Interest in Passion composition waned during the 19th century, but took on new life in the 20th, with major settings by Krzysztof Penderecki, Arvo Pärt, Tan Dun, Osvaldo Golijov, Mark Alburger, and Scott King. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar and Stephen Schwartz’s Godspell contain elements of the traditional passion accounts, as well.

Oratorio’s close relative, opera, perhaps the major formal contribution of the baroque period, was well known in Lutheran Germany. Handel and Telemann, Bach’s contemporaries, were celebrated opera composers, and many German courts and cities had opera houses. The Leipzig town council, in hiring Bach, made their feelings about this modern form clear: he was instructed to “produce such compositions as are not theatrical in nature.” He was not to compose operas, and his music for divine service was not to bear any trace of operatic influence. Opera had briefly appeared in Leipzig shortly before Bach’s arrival, and the city’s response to it had ranged from skepticism to open hostility. It is clear that Bach understood the possibilities inherent in operatic styles and procedures, and that his church music compositions, especially his cantatas, had already begun to absorb characteristics of this art form; it is also clear that in composing his St. John Passion, first presented only ten months after his arrival in town, he chose to disregard the instructions he had been given, and to produce a powerfully dramatic work. Rather than just recite the words of the narrator and characters, he imbued their music with profound expressiveness, in effect creating an imaginary stage for his listeners on which the story unfolds. His later St. Matthew Passion, in which the Biblical narrative is interrupted frequently with lyrical, contemplative passages, seems to be a response to criticism from his employers that his St. John was too operatic and theatrical.

Hearing Bach's Passions

Every year, there are thousands of performances of this work. Musicians and listeners, alike, keep it alive, in expensive, imaginative, carefully researched and rehearsed presentations—and it shows no signs of wear, no signs of diminished impact or declining reputation.

Daniel Melamed begins his 2005 book, Hearing Bach’s Passions, by paraphrasing Helmuth Rilling, “who reportedly once said that it was all very well that we have original instruments and original performance practices but unfortunate that we have no original listeners.” Melamed goes on to ask, “Is it ever possible for us to hear a centuries-old piece of music as it was heard when it was composed? To put it another way, when we listen to a Bach passion, is it really the same piece Bach wrote in the early eighteenth century?” He then explores and describes the religious, social, musical facts on the ground in Leipzig and the rest of the Lutheran, German-speaking world during Bach’s time, effectively making his case that Bach’s “Great” Passion According to St. Matthew, in its original context, nearly 300 years ago, is indeed not at all the work we hear in concerts today, and that no amount of care for “authenticity” in our preparations for such a performance can change that fact. Bach’s listeners were intimately familiar with much of what they heard in the Passion’s three hours of music. The wealth of hymn tunes (and texts) which serve as the musical and theological foundation of the work, also served as the foundation of German Lutheran religious practice; almost surely, every person in attendance on Good Friday knew each note and word, by heart, and felt “at home” and comfortable when these hymns were sung. Bach’s musical language, though somewhat more complex and difficult than that of his contemporaries, did not come as a bewildering surprise to his parishioners—they experienced it every Sunday, year in and year out, in the cantatas he regularly presented during weekly worship. His performers played, and sang, on instruments, and in a style, which were the everyday norm; no one had to accept sounds or expressions which were outside their normal experience. Though the words of the Evangelist and the chorales were in a somewhat archaic German, it was still a German which the listeners understood; and the arias were settings of contemporary German poetry. All of the listeners were officially and legally Lutheran, and subscribed to the theology Bach presented; I suspect they participated in annual presentations of the Passion narrative worshipfully and unquestioningly. Twenty-first century listeners might find the work’s length daunting, but this was nothing to his original hearers: they also sat through a two hour sermon inserted between parts one and two, plus a number of motets and prayers, and endured all of this in an unheated church.

Modern audiences, on the other hand, approach these inescapable aspects of Bach’s work from a tremendous distance, and would seemingly face an impossible task in overcoming this distance; to properly appreciate Bach’s accomplishment, one would think, they would need to take on a special, informed persona, an impossible task. Altogether, our current experience of Bach’s Matthew Passion is, as Melamed and Rilling suggest, irrevocably removed from the experience of Bach’s original listeners.

So why present it?

Well, the fact is, we do. People want to hear it. Every year, throughout the world, there are thousands of performances of this work-- and these performances are far more than dutiful recitations of a hoary museum piece of which we are all told to be in awe. Musicians and listeners, alike, keep it alive, year after year, in expensive, imaginative, carefully researched and rehearsed presentations—and it shows no signs of wear, no signs of diminished impact or declining reputation. Despite changing musical tastes, religious constructs, linguistic traditions, technological developments, performance styles—aspects of our material and intellectual culture which come and go with increasing rapidity-- Bach’s Great Passion shines like a beacon over all, strikes fire in some universal human heart, touches and releases some universal soul.

Chicago Chorale’s production will reflect our own “realities on the ground”: the membership of our ensemble, our performance venue, the soloists and instrumentalists available to us, the amount of money we have to spend on our production, the expectations we have of our audience. On the most basic, material level, it will be Chorale’s take on Bach’s Great Passion, not Leipzig’s. But I am confident that the core value of the work will shine through for us and for our audience, as it did for Bach and his listeners. This music is that big.

Onward and upward

Every musician I know, who has lived with Bach's Matthew Passion, has in some respect been broken, shattered, and remade through the experience.

I fervently wish a happy new year for all of us, an increase in joy and prosperity, a lessening of pain, sorrow, and hardship. Here’s hoping that the coming year brings with it the compassion, the expanded understanding, the mercy, joy, and peace, about which we sing in so much of our music. Next Wednesday, Chicago Chorale begins rehearsing J.S. Bach’s Passion According to St. Matthew, which we will present on Sunday, March 29, at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel. This work is not new to Chorale: we performed it in March, 2008, at Chicago’s Church of the Holy Family; and I have sung it, personally, on several occasions. But it will be new to many of our singers and instrumentalists; and, effectively, it is new each time one performs it-- a piece so large, so rich and multi-faceted, yields new secrets, new complications, new insights, each time one approaches it. The sheer size and scope of it guarantees that any production of it will challenge us and require our utmost concentration and commitment.

I last sang in a production of the Matthew Passion six years ago, just months after conducting it myself, at the Oregon Bach Festival, under the leadership of Helmuth Rilling. Mr. Rilling knows the work, as scholar and as performer, as well as anyone on the planet; he has written and lectured extensively on it, and has conducted it hundreds of time, which he does entirely from memory—an incredible feat. In this particular performance, we had nearly reached the end, when his memory and concentration slipped, and he miscued the tenor singing the Evangelist role, and the continuo players supporting him. It was a small thing, almost surely unnoticed by the audience; to the Evangelist and the continuo players, however, as well as to the rest of us on stage who were following in our scores, it seemed enormous; after nearly three hours of the most intense concentration and involvement, we were living every note, every word, every gesture, along with Mr. Rilling. It felt as though he, and the rest of us, had approached the holy of holies, and had stumbled at the last moment, on the top step. After the applause and curtain calls, he retreated to his favorite place, outside the stage door, and lit up his accustomed cigar; it was clear he did not want to be approached by anyone except his family and closest friends. I walked by, keeping my distance, when he called out to me—“You—you know the mountains and valleys of this piece.” That was all. I was embarrassed; I thanked him for enabling me, and us, to be owned once again by this incredible work, then moved out of range.

This experience illustrates, for me, the essential, terrifying, humbling truth about this work: Bach’s Matthew Passion is indeed the holy of holies, the most comprehensive and influential single work of musical and dramatic art, reaching past the Western musical canon and the particulars of the Christian faith to describe, through music of unbearable beauty and power, the essentially tragic nature of our human condition. None of us can know it, can encompass it, can claim it as our exclusive property, can in any respect conquer it. Every musician I know, who has lived with this work, has in some respect been broken, shattered, and remade through the experience. Its mountains and valleys are the human condition, the life we lead on this earth. How this incredible vision, in all its complexity, can have been transmitted to us through the medium of the Cantor of Leipzig, has been the subject of countless books, articles, sermons, lectures, pronouncements; Bach’s legacy, indeed, “boggles the mind.” Chorale will endeavor, over the coming months, to come to an informed grip on both this legacy, and on the music which inspires it. I hope you will join us—both in exploring this legacy, and in experiencing our performance, on March 29.

Solemn Vespers for the Third Sunday in Advent—on Saturday!

The monastery’s beautiful chapel is an acoustic gem—one of the really sublime spaces to hear choral music in the city.

Almost since our founding, back in 2001, Chicago Chorale has sung in various liturgies and concerts at Monastery of the Holy Cross, at the corner of 31st Street and Aberdeen, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. The monastery’s beautiful chapel is an acoustic gem—one of the really sublime spaces to hear choral music in the city. The Benedictine monks who live there, take full advantage of this beauty, chanting appropriate psalms and liturgies several times a day, day in, day out, throughout the church year. Their prior, Father Peter, was, in a former life, a University of Chicago undergrad, who majored in music and participated fully in the musical opportunities the University had to offer; and he has carried his love of good music, his erudition in selecting and performing it, and his skill in teaching others to perform it, into his life in the Monastery.

Some years ago, Father Peter and I settled upon a model for a choral advent service, very different from most such services in the city. Completely eschewing the warm, somewhat sentimental approach of most such services (which tend to focus more on the actual Christmas event, the birth of Jesus, rather than upon the period leading up to the birth), Father Peter strictly follows the texts and rubrics for the season, acknowledging the historical character of Advent as “a little Lent”—a time for reflection and self-examination, for acknowledgment of our darkness and of our yearning for enlightenment and salvation. He adapts the Solemn Vespers liturgy to the season, retaining the elements that are part of every Vespers service, every day—the Magnificat, the Pater noster, the chanting of psalms-- and then enriches this framework with the addition of polyphonic settings of such hymns as Alma Redemptoris Mater and Conditor alme siderum, and appropriate motets ( this year, Ecce Domins veniet).

Almost since our founding, back in 2001, Chicago Chorale has sung in various liturgies and concerts at Monastery of the Holy Cross, at the corner of 31st Street and Aberdeen, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. The monastery’s beautiful chapel is an acoustic gem—one of the really sublime spaces to hear choral music in the city. The Benedictine monks who live there, take full advantage of this beauty, chanting appropriate psalms and liturgies several times a day, day in, day out, throughout the church year. Their prior, Father Peter, was, in a former life, a University of Chicago undergrad, who majored in music and participated fully in the musical opportunities the University had to offer; and he has carried his love of good music, his erudition in selecting and performing it, and his skill in teaching others to perform it, into his life in the Monastery.

Some years ago, Father Peter and I settled upon a model for a choral advent service, very different from most such services in the city. Completely eschewing the warm, somewhat sentimental approach of most such services (which tend to focus more on the actual Christmas event, the birth of Jesus, rather than upon the period leading up to the birth), Father Peter strictly follows the texts and rubrics for the season, acknowledging the historical character of Advent as “a little Lent”—a time for reflection and self-examination, for acknowledgment of our darkness and of our yearning for enlightenment and salvation. He adapts the Solemn Vespers liturgy to the season, retaining the elements that are part of every Vespers service, every day—the Magnificat, the Pater noster, the chanting of psalms-- and then enriches this framework with the addition of polyphonic settings of such hymns as Alma Redemptoris Mater and Conditor alme siderum, and appropriate motets ( this year, Ecce Domins veniet).

The monastery’s chapel is particularly suited to polyphonic, unaccompanied music, performed by a smaller group of light, clear voices—so each year I choose a subset of Chorale’s singers who are particularly adept at this repertoire, and enthusiastic about the disciplines that go into performing it. Father Peter is interested in the historic background of Roman Catholic music, and in experiencing it in its appropriate role as liturgical, rather than concert, music. Each year, we explore the liturgical music of a particular composer—music one would usually hear in concerts by groups which specialize in renaissance music, but less and less in actual liturgical practice. This year’s composer, Tomás Luis de Victoria, was the most famous composer in 16th-century Spain, and one of the most important composers of his era. He studied in Rome with Palestrina; but his music has a brooding, emotional quality very different from that of his teacher, and appeals viscerally to modern listeners in a way Palestrina’s sometimes doesn’t. Many singers claim Victoria as their favorite renaissance composer: not only does he write beautiful lines which combine in beautiful harmonies, but he appeals to the heart and the feelings.

If you are free at 5 PM this Saturday afternoon, December 13, come and experience this beautiful service in this beautiful space. We request a donation of $15, but are happy for anything you can give; mostly, we want to you come and hear us, to step into a world of peace, quiet, and stillness and let all the elements of this Vespers service have their way with you.

Saturday, December 13, 5 PM, Monastery of the Holy Cross, 3111 South Aberdeen Street.

Mozart wrap up

Chorale’s rousing success with Mozart’s Mass in C minor says many things about our group.

Chorale’s rousing success with Mozart’s Mass in C minor says many things about our group. First: our unwavering faith in our ability to handle the finest music available to us, though it seems at times preposterous, actually enables us to rise to the occasion, accomplish the musical and linguistic requirements presented by the task before us, at a level few of us would be able to accomplish on our own. We have learned, over the years, that organized hard work toward a worthy goal is a powerful motivator. Chorale’s singers start out expecting, even demanding, the right to learn and present great music; but that can be a pretty nebulous goal, until put to the test. Our singers tend not to waver and fold when truth smacks them in the face; rather, they are energized by the demands of the task before them, and expand, joyfully, to fill whatever shoes need filling. This is simply the character of the singers who constitute our ensemble; every conductor should be as lucky as I am, to have such personalities in his choir.

Second: there really is an audience out there, for the sort of music Chorale chooses to present. Chicago is a big city, and the task of contacting, and attracting, those who love great music, can be daunting; but the size, and palpable enthusiasm, of the audience who heard us in Orchestra Hall—the place was packed!-- convinces us that we are on to something, in our repertoire focus. These people love Mozart. It is so important to me, and to the group, to know that we are on the right track, in programming such repertoire. Chorale has to learn better how to market ourselves, in order to get these same music lovers to come again and again to hear us; but we have now seen about 2,500 of them, we know they are out there, and they have heard us.

Third: our demanding, never-ending search for appropriate collaborators pays off. We thoroughly enjoyed working with Civic Orchestra of Chicago, and felt pushed by their standard, to raise our own; and in Nicholas Kraemer we found a conductor who could really appreciate our musical values and ideals, guide us in making sense of the music on the page, and help us put it all together in a finished performance. His musical ideas, honed by many years of working with first class chamber and period ensembles, both as player and as conductor, matched very well with Chorale’s disciplines and goals; effectively, he spoke a language we had already studied, and he hastened our learning. We were never confused by him; he wanted what we wanted, and he taught us to want it at a higher level.

Finally: we had so much fun! Doing great music to the best of our ability is fun. The tension and stress of getting to that level, though palpable in rehearsals, melts away once we get in front of an audience. The greater the challenge, the higher the level of our performance, surely; but also, the higher the level of our enjoyment! Doing great music well, is a sublime joy.

Iron fist in a velvet glove

Our Mozart Mass in C minor now belongs to Nicholas Kraemer. Please come and hear what he does with it!

Chorale’s first rehearsal with Nicholas Kraemer was very exhilarating and exciting. The singers were prepared, and on their best behavior: they arrived on time, they uncrossed their legs and sat up straight, they watched the conductor, they shone with enthusiasm. This must have been very gratifying for Mr. Kraemer—he had just arrived from London, and announced his jet lag, apologizing in advance for any shortness of temper he might display (there was none). Throughout the afternoon, watching and listening to Mr. Kraemer rehearse, I repeatedly thought of a phrase I first heard in a master class with soprano Elly Ameling and pianist Dalton Baldwin, more than thirty years ago: “iron fist in a velvet glove.” Referring specifically to a song by Gabriel Fauré, Ms. Ameling warned a singer not to give into his feelings, to his romantic impulses, but to submit them to the rule of the tempo, the pulse. She told us that the truth of Fauré’s musical language lies in the tension between these two poles: the unwavering firmness of his forward movement, and the emotion expressed through his harmonies and melodies.

I often use this phrase, and principle, when rehearsing Chorale. We all feel the beauty and emotional satisfaction inherent in the music we perform; but we can’t afford to skip, or even skimp on, establishing what I call “the grid”: the pitches, up and down, and the rhythms, from here to there. Chorale members spend an amazing amount of time nailing down pitches and rhythms, both on their own time and in group rehearsal. I do my best to let nothing slide, to correct every error, to clarify each rhythmic subdivision—I always imagine some bright music student taking dictation, and try to produce something he can hear and transcribe. I remember very well a phrase Harry Keuper used in describing Robert Shaw’s nagging perfectionism: “toilet trained at the point of a gun;” and I wonder if my singers say something similar, of me.

To some extent, I have become this way out of a desire to overcome my own unbridled feelings and impulses when enjoying music. Elly Ameling was speaking to me; and years of studying and performing with Dalton Baldwin, Robert Shaw, and Helmuth Rilling have developed a hyper-awareness in me of the many ways there are to indulge oneself and get off track. But I also realize on my own, that when a large group of singers gets together, they can very easily become an amoeba, spreading formlessly all over the place and leaving structure and coherence behind, no matter how much they love what they are doing, no matter how good they feel about themselves. Yet I am on guard that I not suppress the wit, style, and life of the music-- the velvet glove-- in order to keep the amoeba corralled. Fauré’s music needs work with a metronome; it also needs acknowledgement and nurturing of its silk and velvet soul.