Knut Nystedt-- an early minimalist?

This is undoubtedly some of the best choral music currently being written, and we are thrilled to be presenting it.

Spiritual minimalism is a term used to describe the musical compositions of a number of late-twentieth-century and early twenty-first century composers of Western classical music. These compositions tend to have simplified musical materials—a strong foundation in functional tonality or modality; simple, repetitive melodies; straightforward, unchanging meters-- compared with the serial, experimental, often extremely complicated styles which had been the prevailing practice in the preceding years. This seeming look backward has been labeled neo-romanticism and post-modernism by some, as it seems to return to the lyricism of the nineteenth century. Most of these composers focus on an explicitly religious orientation, and look to Renaissance and medieval sacred music for inspiration, as well as to the liturgical music of the eastern orthodox churches. Three of these composers-- Arvo Pärt, John Tavener, and Henryk Górecki-- have had remarkable popular success, being featured on CDs which have sold, worldwide, by the millions. Despite being grouped together, these composers work independently and have very distinct styles, and tend to dislike being labeled with the term “spiritual minimalist;” they are by no means a "school" of close-knit associates. Their widely differing nationalities, religious backgrounds, and compositional inspirations make the term problematic; nonetheless, it is in widespread use, perhaps for lack of a better term.

Norwegian composer Knut Nystedt (1915-2014) is the earliest composer to be represented on Chorale’s November concerts. He composed the motet we will sing, Audi, in 1968, as one movement of a larger, orchestrated oratorio, Lucis Creator Optime, and then adapted it for a cappella choir. His name does not usually appear in a listing of minimalist composers—he was very much a regional phenomenon, a Norwegian church musician who listed Aaron Copeland as his principal teacher.

But the evidence at hand—the musical nature of Nystedt’s compositions-- tells an interesting story, and one which for me sheds light on essential characteristics the minimalist composers share. Though predating the seminal figures of this compositional trend by some twenty years, Nystedt clearly pursued many of the same ideals and goals. Like them, he composed primarily choral settings of biblical and liturgical texts, and did so with an ear for sonorous combinations of sounds which would enhance the emotionality of the texts through relatively simple means- short, repeated melodic phrases and motifs, which build and subside through layering techniques which at first glance seem surprisingly simple; cool, traditional harmonic colors; slow-moving and unvarying rhythms. And above all, fidelity to the sacred texts he has chosen-- as a composer for Christian worship, he sought appropriate colors for presenting text to his listeners as emotion and transcendence, rather than as rational explication. He claimed the sacred music of Palestrina as his principle inspiration, but delved deeply into modern techniques of musical expression.

There is something subtly but very clearly “northern” about Nystedt’s music—a plainness, a coolness with interjections of warmth (more cool than warm), a particular combination of light and dark (far more dark than light) which I hear in all of the music we will present in this concert—and which seems an essential characteristic of this minimalist “school,” close-knit or not. In my ears, Audi sounds like the souls of the damned, lost and alone and crying out in space, up with the Northern lights-- a quality I hear as well in Pärt’s music, particularly, and in that of other, far younger composers represented on our program. I hope you will come and hear it—this is undoubtedly some of the best choral music currently being written, and we are thrilled to be presenting it.

Kit Bridges, Chorale's Rehearsal Accompanist

A good rehearsal accompanist can be essential to a choir’s success.

A good rehearsal accompanist can be essential to a choir’s success, especially a larger choir, like Chorale. If the conductor is tied to the piano, constantly giving pitches, playing parts, helping with tricky passages, he cannot focus on his singers—their sound, their vocalism, their ensemble production. And a mediocre to bad accompanist—one that lacks personally artistry, that doesn’t listen to the conductor or the singers, is not attuned to the conductor‘s preferences and needs, does not anticipate the conductor’s ideas and techniques, and does not mirror these things in his playing-- is even worse than no accompanist at all. If an accompanist slows the rehearsal down, it is better for the conductor to struggle at the keyboard himself, bad as that is; at least he can keep the pacing of the rehearsal up.

A good rehearsal accompanist can be essential to a choir’s success, especially a larger choir, like Chorale. If the conductor is tied to the piano, constantly giving pitches, playing parts, helping with tricky passages, he cannot focus on his singers—their sound, their vocalism, their ensemble production. And a mediocre to bad accompanist—one that lacks personally artistry, that doesn’t listen to the conductor or the singers, is not attuned to the conductor‘s preferences and needs, does not anticipate the conductor’s ideas and techniques, and does not mirror these things in his playing-- is even worse than no accompanist at all. If an accompanist slows the rehearsal down, it is better for the conductor to struggle at the keyboard himself, bad as that is; at least he can keep the pacing of the rehearsal up.

A good accompanist is more than a good pianist. He is even more than a good musician. He is completely attuned to the needs of the conductor and the group, and uses his energies and talents to help the choir sound better, and to help the conductor do a better job. His work serves as the rehearsal’s foundation.

Chorale is blessed with such an accompanist.

I first met Kit Bridges when he and I were grad students at Northwestern University. He accompanied the studio of Norman Gulbrandsen, which included most of the best singers at the school—and he played like a god. He brought technique, sensitivity, artistry, to what can be a very boring and perfunctory position, and made his singers sound like polished artists, even if they were too thick to know he was doing it. I started out in a different studio, with a different accompanist; one of the principle reasons I finally switched to Gulbrandsen, was to work with Kit. He exemplified for me the kind of collaborative artistry I heard in the recordings of Dalton Baldwin and Gerald Moore—and I wanted that sort of a musical experience, more than anything else. That was many years ago, now; but I have been privileged to work with Kit in one capacity or another ever since, and was thrilled past my wildest dreams when, three years ago, he agreed to serve as Chorale’s regular accompanist.

It is a little like hitching a thoroughbred to a plow—why should someone with Kit’s abilities, be sitting at a piano bench, giving pitches to a choir? But he even gives pitches artfully! And the grace with which he plays our warm ups, pulls more out of the unwitting choir, than any amount of verbiage from me can. Besides, it fills me with such security and confidence to have him there—he can hear what is going wrong when I can’t, can pinpoint problem areas and fix them, ever so quietly and unobtrusively, while I am struggling with other issues.

Most members of Chorale have little idea of what Kit does during the rest of the week—the classes he teaches, the singers he coaches, the recitals he plays, the major auditions he accompanies. They take him gloriously for granted. But I know that we have the very best, right there in the room with us-- and that he helps Chorale be the very best we can be.

Excelsior! Chicago Chorale begins its 15th Season

The music is simply astounding in its beauty, its range of expression, in its sheer sonic mystery. You won’t want to miss this.

Chorale had an eventful summer. Our concert tour to the Baltic countries was an unqualified success-- we sang in magnificent, acoustically rich venues, for standing room-only audiences; we ate wonderful food, drank exotic local beverages, in great variety and abundance; we stayed in fabulous hotels; we saw and became acquainted with interesting, beautiful countries, each of which had its own compelling story; and we all made it back home, safe and sound.

Less than a week later, we began rehearsals for the screening of the Gladiator movie at Ravinia, music track provided by Chorale and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. We invited singers from throughout the Chicago area to join us in this venture, and had, as always, a wonderful time, in a venue and setting unlike anything else we do.

Since then, the singing aspect of the ensemble has been on hiatus, while the administrative wheels have been turning, preparing for our fifteenth anniversary season, finishing the season brochure, readying music for the singers, completing our roster. Now, rehearsals kick in, new singers find their way into the group’s sound and ethos, and we begin learning our concert program for this fall.

Our autumn concert, entitled Arvo Pärt at Eighty, celebrates the career achievement of one of the most important living composers, Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. How fortunate for Chorale, that we were able to sing on his home turf just this past summer, presenting concerts in both Haapsalu and Tallinn. So much of his music is a reflection of his home country, of the sky, the sea, the forests, the White Nights of summer and the dark days of winter-- and we feel enriched by our experience of these things, as we approach his music. We were fortunate to share a concert with an Estonian choir singing predominantly Pärt’s music, in Tallinn—to hear their vocal color and approach, their articulation style (reflecting the Estonian language), their particular type of expressiveness-- all aspects of musical performance that cannot be notated.

About half of our concert will consist of Pärt’s music; the other half will feature individual pieces by composers contemporaneous with him, influenced by him, perhaps even influential on his compositional development. These composers include the Norwegian composer Knut Nystedt, Swede Jan Sandström, Latvian Rihards Dubra, Lithuanian Vytautis Miskinis, Estonian Urmas Sisask, Pole Henryk Gorecki, and Britisher John Tavener-- a virtual who’s who of the spiritual minimalist movement in choral composition.

We will present our concert twice: Friday, November 20, at Hyde Park Union Church, and Saturday November 21, 8 PM, at St. Vincent De Paul Parish, in Lincoln Park. Season subscriptions, as well as individual tickets, will soon be available on our website. We hope to see you at one of these concerts! The music is simply astounding in its beauty, its range of expression, in its sheer sonic mystery. You won’t want to miss this.

Baltic Tour Concert Details-- maybe you'll be there to here us!

If you happen to be in the neighborhood, please come and hear us!

Wed 8 July KAUNAS Kaunas Basilica 7 PM Thur 9 July VILNIUS St. Kasimir's 7 PM

Sat 11 July RIGA St. Peter's Church 6 PM

Mon 13 July HAPSAALU Hapsaalu Dom 6:30 PM

Tue 14 July TALINN St. John's Church 7 PM

Thur 16 July HELSINKI Church of the Rock 7 PM

Many of our singers have already left, and are travelling through other parts of Europe before gathering in Vilnius. Good for them! They are having a great time, and will be thoroughly over jet lag by the time the rest of us arrive. Excitement is running high, on both sides of the Atlantic. If you happen to be in the neighborhood, please come and hear us!

Excelsior! Onward and Upward

Our musically and emotionally successful Da pacem Domine spring concert now behind us, Chorale faces a busy summer.

Our musically and emotionally successful Da pacem Domine spring concert now behind us, Chorale faces a busy summer. Twenty-seven of our members will travel to the Baltic countries and present performances of the music we sang last week: July 8 in Kaunas, Lithuania

July 9 in Vilnius

July 11 in Riga, Latvia

July 13 in Haapsalu, Estonia

July 14 in Tallinn

July 16 in Helsinki

Few of our number have ever set foot in any of these countries, and anticipation runs high in the group, as well as the prevalence of preparatory study (we are, after all, a group of educated nerds). In the weeks before our departure, we are rehearsing to adapt our sound and interpretation to a smaller group. Then, on Sunday, June 28, at 3 PM, we will present our “kick-off concert” at Monastery of the Holy Cross, 31st and Aberdeen, in Bridgeport. We expect that the leaner sound produced by twenty-seven voices will be particularly beautiful in this acoustically resplendent space, and we urge all of our constituency—friends, our regular audience, current members who are not making the trip, and anyone else who is curious-- to come and cheer us on. Tickets are a very modest $10, available either on line or at the door. Whatever you may have to miss that afternoon, to carve out time to hear us, I promise you won’t be disappointed: the choir, the repertoire, and the space, will blow you away. This concert was made for Monastery of the Holy Cross…

Several of our singers will leave for Europe right after the concert, to do some private travel, visit friends, and overcome jet lag; the rest of us will fly over to meet them on July 6. Most of us will return to Chicago on July 17, and immediately begin preparations for our performance at the Ravinia Festival. This summer, we will sing the choral portion of the musical score to the movie Gladiator, accompanied by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Justin Freer, conductor, on Sunday, August 2, at 7 PM. These events, at which the film is shown, both on a large screen in the pavilion and on other screens around the park’s grounds, while the music is performed live on the pavilion’s stage, have proved to be major draws, attracting enormous, enthusiastic audiences. Chicago Chorale is extremely fortunate to have been chosen, for a fourth time, to participate; it is the summer’s highlight, for many of our singers.

We will announce our 2015-16 season within the next couple of weeks, after all details have been nailed down. As a teaser, I can say now that we will present an Arvo Pärt 80th birthday tribute in late November; Rachmaninoff’s Vespers in mid-March; and music by Joby Talbot and Herbert Howells in early June. Glorious music sung in wonderfully reverberant spaces. Please plan to purchase a subscription this year, if you have not already been in the habit of doing so; you won’t want to miss any of this wonderful music.

This spring's early music

We are including a few pieces of earlier music, which suit our size, our sound, and our preferences.

When putting our Da pacem, Domine program together, I did not intend to be dogmatic about chronology or style. Circumstances require that all of our selections be unaccompanied; theme dictates that texts, and mood, be of a contemplative, peaceful nature, suggestive both of sadness and of joy. I considered, too, the general preferences of the singers: after a season heavy on major, orchestrated works, I thought they would welcome something smaller, more intimate, more nuanced. All of this had to be passed through the refining filters of available rehearsal time, vocal and musical resources, and some hopeful guesses about what our audience would appreciate. Not surprisingly, we ended up with a program heavy on twentieth century. We are a large group (sixty singers), and half of us are women. Most choral music composed before the eighteenth century is better served by smaller ensembles staffed with early music specialists, especially counter tenors and women who can sound like boys; most choral music composed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is accompanied by keyboard or other instruments. With notable exceptions, important a cappella choral music took a break during this period, to re-emerge in the twentieth century as a vital, center-stage art form.

Nonetheless, we did include a few pieces of earlier music, which suit our size, our sound, and our preferences.

Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672), the greatest German composer before Bach, studied extensively with Giovanni Gabrieli in Venice (1609-1612), and returned to that city in 1628 to meet and work with Claudio Monteverdi. He learned progressive, polychoral techniques from them, and composed a good deal of music in this grand, elaborate style, for multiple choirs of voices and instruments, as court composer to the Elector of Saxony, in Dresden. The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), however, gradually took its toll on his opportunity to produce such works: the longest and most destructive conflict in European history, it devastated, among other things, the musical infrastructure of Germany, and pushed Schütz toward a simpler, more austere style later in his career. In the forward to his 1648 publication, Geistliche Chormusik, he describes the contents as “sacred choir music with 5, 6, and 7 voices to be used both vocally and instrumentally…the general bass can be used at the same time if liked and wanted but it is not necessary.” The twenty-nine pieces in the collection react to the events of the time with traditional Biblical texts, several of them pleas for peace. Chorale will sing the 5-voice motet, Die mit Tränen Säen, a setting of Psalm 126:5-6—

They that sow in tears shall reap in joy. They go out with weeping, bearing precious seed, and come back in joy, bearing their sheaves.

Schütz expresses the text’s contrasting elements—tears/joy, go out/come back, sow/reap—with remarkable economy of means, juxtaposing long and short phrases, dissonant and consonant harmonies, painfully slow passages with quick, joyous ones, all in a strikingly efficient composition, short and simple enough for the reduced forces with which he was working at the time.

One of the “notable exceptions” referred to above is Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824-1896), who put some of his best efforts into composing choral music. Associated with the Roman Catholic Church throughout his life, Bruckner was able to combine elements of his daring, avant garde symphonic style with the conservative, Gregorian-based music required by the church hierarchy, and produce a body of church music, both a cappella and accompanied, unsurpassed by other composers of his century. Chorale will sing one of his Marian motets, Virga Jesse floruit (1885), which sets a Gradual text from the Feast of the Assumption:

The rod of Jesse hath blossomed: a Virgin hath brought forth one who was both God and man: God hath given back peace to man, reconciling the lowest and the highest to Himself.

Like Schütz, Bruckner skillfully expresses the contrasts in his text-- God/man, lowest/highest—through direct, efficient musical means, especially through the careful notation of dynamic change, from ppp to fff, and the use of a very wide vocal range: from the top soprano note to the lowest bass note spans three and a half octaves.

A generation later than Schütz, Henry Purcell (1659-1695) is celebrated as England’s greatest and best-known native composer, at least up to the twentieth century, despite his short life. Nominally organist of Westminster Abbey, he contributed to all the musical genres available to him, both instrumental and vocal, and is as noted for his secular, theatrical compositions, as for his church anthems. Chorale will sing Hear my prayer, O Lord, which exists only as an incomplete fragment in the library of Cambridge University, though it is thought to form the opening movement of a longer anthem. Only two and a half minutes long, the piece consists of the working-out of only two short motives, each set to a particular line of text from Psalm 104: 1) Hear my prayer, O Lord, and 2) and let my crying come unto Thee. The first is a concise, chant-like phrase consisting of only two pitches; the second, contrasting, phrase consists of a longer, rising chromatic motive. Over the course of only thirty-four measures, utilizing only these two motives, Purcell gradually amplifies the vocal texture, and intensifies the harmonic complexity, until all eight voices combine in an overwhelming, dissonant tone cluster, before resolving in the final cadence.

In the latter years of the twentieth century, a number of composers attempted to “complete” Purcell’s fragment, by composing companion movements, using elements of Purcell’s work but expanding them with modern harmonic and rhythmic procedures. Chorale will sing the

completion composed by British composer and conductor Bob Chilcott (b.1955). Published by Oxford university Press in 2002, OUP’s catalogue describes it as “a technical 'tour de force', meticulously sculpted from the distilled essence of Purcell's original and yet always recognizably Chilcott. The music is involved, passionate, and frequently contrapuntal. This is a beautiful and convincing work imbued with an unsettling melancholy.” There you have it.

Ellen Hargis, soprano, will sing with Chicago Chorale

When Ellen sings with Chorale, soprano members of our group inevitably comment, “I wish I could sing just like that. That is what I would sound like, if I could; and that is just the way Bach should be sung.”

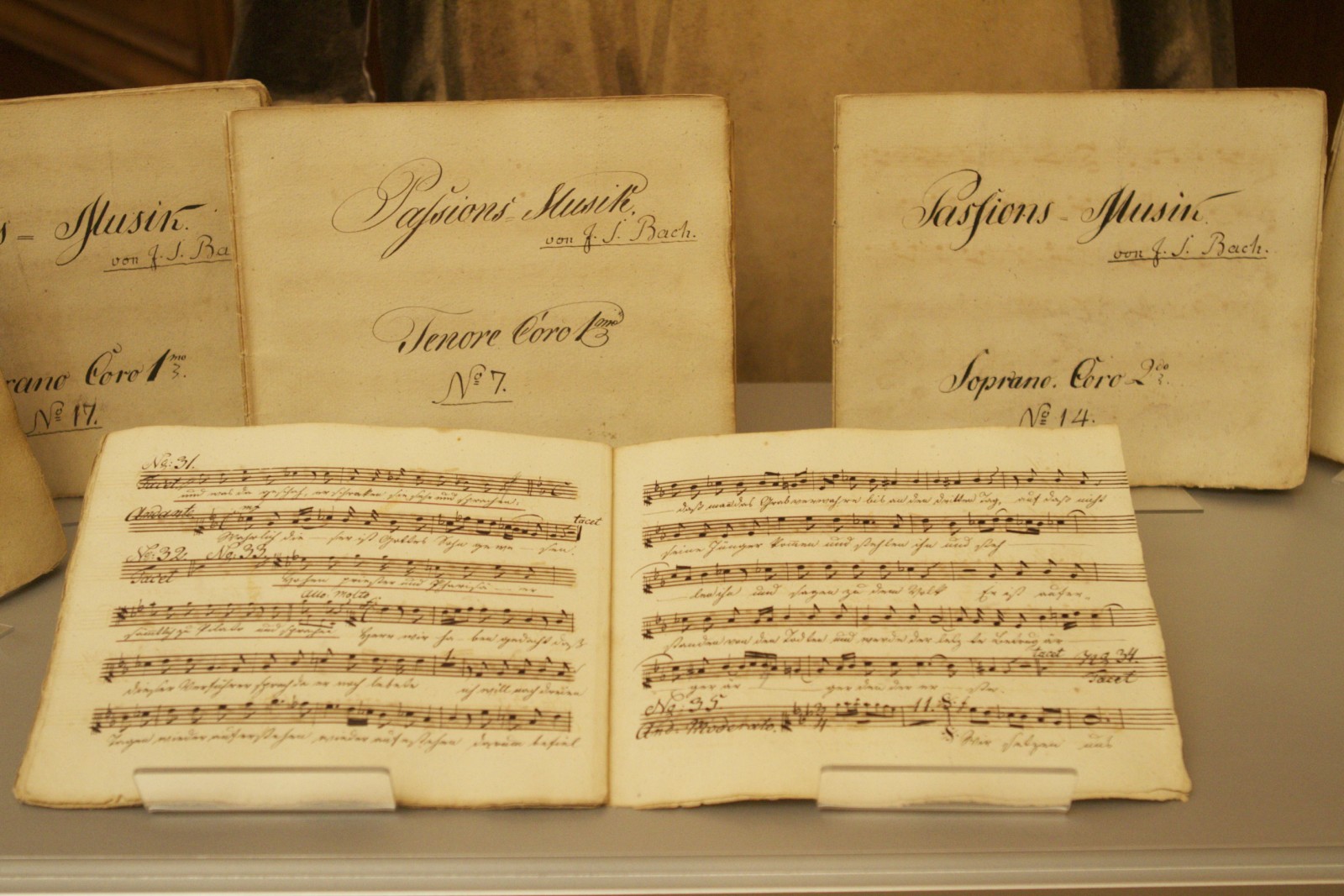

Two years ago, Ellen Hargis sang the soprano solos in Chicago Chorale’s performance of Bach’s St. John Passion. Lawrence Johnson, in Chicago Classical Review, wrote, “Sunday’s performance…benefited from some superb vocal soloists…Ellen Hargis’s clear, expressive singing and bell-like tone in her two arias made one wish the soprano had more to do in this work.“ Well, Ellen is back this season, singing the arias in the St. Matthew Passion; and Bach has granted that wish: she sings in no fewer than eight separate numbers. Her artistry and assured presence enliven all who perform with her— conductor, singers, and instrumentalists; and the audience easily senses the authority and appropriateness of her performance. Music of earlier times, becomes the living music of today, through her committed, gracious, engaged singing.

Chicago is incredibly fortunate to have an artist and teacher of Ellen’s stature living and working right in our midst. She is one of America's premier early music singers, specializing in repertoire ranging from ballads to opera and oratorio. She has worked with many of the foremost period music conductors of the world, including Andrew Parrott, Gustav Leonhardt, Daniel Harding, Paul Goodwin, John Scott, Monica Huggett, Jane Glover, Nicholas Kraemer, Harry Bickett, Simon Preston, Paul Hillier, Craig Smith, and Jeffery Thomas. She has performed with The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, The Virginia Symphony, Washington Choral Arts Society, Long Beach Opera, CBC Radio Orchestra, Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Tragicomedia, The Mozartean Players, Fretwork, the Seattle Baroque Orchestra, Emmanuel Music and the Mark Morris Dance Group.

Two years ago, Ellen Hargis sang the soprano solos in Chicago Chorale’s performance of Bach’s St. John Passion. Lawrence Johnson, in Chicago Classical Review, wrote, “Sunday’s performance…benefited from some superb vocal soloists…Ellen Hargis’s clear, expressive singing and bell-like tone in her two arias made one wish the soprano had more to do in this work.“ Well, Ellen is back this season, singing the arias in the St. Matthew Passion; and Bach has granted that wish: she sings in no fewer than eight separate numbers. Her artistry and assured presence enliven all who perform with her— conductor, singers, and instrumentalists; and the audience easily senses the authority and appropriateness of her performance. Music of earlier times, becomes the living music of today, through her committed, gracious, engaged singing.

Chicago is incredibly fortunate to have an artist and teacher of Ellen’s stature living and working right in our midst. She is one of America's premier early music singers, specializing in repertoire ranging from ballads to opera and oratorio. She has worked with many of the foremost period music conductors of the world, including Andrew Parrott, Gustav Leonhardt, Daniel Harding, Paul Goodwin, John Scott, Monica Huggett, Jane Glover, Nicholas Kraemer, Harry Bickett, Simon Preston, Paul Hillier, Craig Smith, and Jeffery Thomas. She has performed with The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, The Virginia Symphony, Washington Choral Arts Society, Long Beach Opera, CBC Radio Orchestra, Freiburg Baroque Orchestra, Tragicomedia, The Mozartean Players, Fretwork, the Seattle Baroque Orchestra, Emmanuel Music and the Mark Morris Dance Group.

Ellen performs at many of the world's leading festivals including the Adelaide Festival (Australia), Utrecht Festival (Holland), Resonanzen Festival (Vienna), Tanglewood, the New Music America Festival, Festival Vancouver, the Berkeley Festival (California), and is a frequent guest at the Boston Early Music Festival.

Her discography embraces repertoire from medieval to contemporary music. She has recently recorded the leading role of Aeglé in Lully's Thésée for CPO, nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording in 2008, as well as Conradi's opera Ariadne, also nominated for a Grammy Award. She is featured on a dozen Harmonia Mundi recordings including a critically acclaimed solo recital disc of music by Jacopo Peri, and in Arvo Pärt's Berlin Mass with Theatre of Voices, and two recital discs with Paul O'Dette on Noyse Productions.

Ellen Hargis teaches voice at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, and is Artist-in-Residence with the Newberry Consort at the University of Chicago and Northwestern University. Her local performances with the Newberry Consort, in Hyde Park, Evanston, and downtown, are highlights of the Chicago concert season. Follow this link for more information about the her performances this weekend!

When Ellen sings with Chorale, soprano members of our group inevitably comment, “I wish I could sing just like that. That is what I would sound like, if I could; and that is just the way Bach should be sung.” I invite you to come hear what they mean, March 29, 3 PM, at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel.

The Living Bach

The Matthew Passion awes through its brilliance, genius, monumental achievement. Beyond this, though, it speaks of pity, compassion, love and reverence for all creation. Matthew’s story is the human story, reenacted every day in every corner of our globe.

After three week’s medical hiatus, I am back at this. During those three weeks, I listened almost daily to recordings of Bach’s Matthew Passion; during the third week, I was able to follow along in the score, and actually do some private rehearsing. I had many quiet hours to think about the work, to consider its meaning and relevance for today’s listeners, as well as to marvel at the skill of the performers on these recordings, and try to learn from what they were doing. Art works from the early eighteenth century tend to end up in museums-- or as museums, themselves. We walk through museums, marveling at the incredible skill, art, cleverness of the long dead artists, and of the schools or trends which they represent. We read in visitors’ guides about religious or social movements of the period; we discuss and are at least dimly aware of the iconography which indicates deeper meanings than we see on the surface. But it is all long ago and far away; we don’t paint or sculpt or write that way any more, and most aspiring artists, attempting to define a new, personal identity, would not want to learn how.

Music somehow is different. Even with the high-quality recordings available to us, we require that music sound, and that we musicians of today enable that sounding, actually learn to do what musicians did in the eighteenth century. We put on live performances. Audiences want to hear it live; and we want to perform it live. So we work very, very hard, unlike our colleagues in plastic or verbal arts, to produce museum-quality performances. In the process, we must and do ask ourselves-- Why? Does anyone today believe what Bach was attempting to convince his listeners to believe? We now live in a multicultural, multi-religious, even in many respects nonreligious world; few people, if any, subscribe to the homogeneous religious tenets of 1720s Leipzig. Much of the dogma which served as the underpinnings of Bach’s texts has completely disappeared; some aspects of it have been used to justify acts of barbarism and murder, and deeply disturb modern listeners.

Nonetheless, we continue to school ourselves in the performance of Bach’s music, vocal and instrumental. To a great extent, we do this because it is so good, so monumental, and so gratifying to perform and hear. Few composers yield such rewards. It is a commonplace, worth restating, on which listeners and performers from a wide variety of religions and ethnicities agree: Bach is in a class by himself. His music speaks to us all. But what is it, that it speaks? Certainly, it speaks brilliance, genius, monumental achievement. Beyond this, though, it speaks of pity, compassion, love and reverence for all creation. The Matthew Passion, following the words and characterization of Matthew’s Gospel, shows us Jesus the man-- loving, melancholy, impatient, sorrowful, in great pain, finally and horribly alone in his trial and death. As the soprano soloist sings, ”He has done only good for us all; he has returned to the blind their sight, the lame he has made to walk again; he drove the devils out, he has comforted the mourners, took the sinners to himself. Only these things has he done; otherwise, nothing. Out of love, my savior now is dying.” I suspect there is no one who cannot relate to this figure, who does not weep at the horrible calamity of his death. We understand his disciples, from Judas to Peter, who cannot really believe what is coming, and cannot see their own weakness and failing until it is too late. We understand Pilate, intelligent and insightful but helpless, and we understand the fury of the mob. Matthew’s story is the human story, reenacted every day in every corner of our globe.

Each time I read Moby Dick, it possesses me; each time I have sung Winterreise, I have been owned, lock stock and barrel, by Schubert. Bach’s Matthew Passion exerts the same sort of ownership over me. I find myself at the very intersection of the divine and the mortal, where everything on the page and in the air is holy. I hope you will come and share in the fruits of Chorale’s hard work. March 29, Rockefeller Chapel.

An Urban Oasis - Guest post by Megan Balderston

Bruce has been recovering from eye surgery for the last couple of weeks, and has been necessarily absent from the blog. Therefore, a number of us from the choir will be giving our thoughts on the upcoming concert as he recovers. I expect he will have a new post up in the next week or so, himself. As the sometime-singing managing director of this ensemble, I’m sad to say I will not be taking my place amongst the first sopranos during the Passion. The reason is that I am the de-facto producer of this concert, and there are approximately a million moving parts to it. The St. Matthew Passion is a monumental work. We are splitting into double choir, and children’s choir (ably led by Chorale bass Andrew Sons, photo below), and presenting our wonderful period orchestra, and outstanding soloists, some of whom are flying in specifically for the work. We are building a stage to hold everyone in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, and that is an expensive and occasionally nerve-wracking project. Thank goodness for their Dean, Elizabeth Davenport, and her able staff for their thoughtful and methodical approach to fitting everyone on stage.

There are travel arrangements, rehearsals, communicating with everyone… and all the while working on keeping the general business end of things running. No, it’s probably a good thing that I am on hiatus as a singer. Unfortunately, that means that I cannot explain to you, as a singer, why this work speaks to me. But I can give you a few really great reasons to join us on March 29th as we present the work.

Several years ago I was introduced to a gentleman in my neighborhood who, as one does, asked me what I do for a living. As I was explaining Chicago Chorale, he gripped my arm suddenly and said, “Do you perform the St. Matthew Passion?” He then proceeded to get teary-eyed as he told me how profoundly this work touches him, and made me promise to let him know the moment we programmed it again. In all of my life as a musician and arts administrator, I have never had someone break down while chatting casually about a musical work…and at a cocktail party, no less. I was reminded of this several weeks ago when one of our members told me that she makes her children listen to the recording in the car because “It is so beautiful that it makes me weep, and they need to know that kind of music.”

We have had a tough winter here in Chicago. Don’t you owe it to yourself to have a mini-retreat, right here in town? If you have not yet listened to Bach in the glorious space of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, while the afternoon light streams through the windows, you are missing out. Give yourself an afternoon of reflection and beauty.

Finally, as much as I love listening to recordings, music as glorious as this begs for the tension and drama of live performance. When we get excited by something, we also are vulnerable. Singing this work is opening up our singers’ hearts and minds, and they want to share that with you. We hope we see you at our urban oasis: Rockefeller Memorial Chapel on March 29th.

Angela Young Smucker, Alto Soloist in Chorale's Matthew Passion

Bach intended that these solos be sung by members of the chorus; but they are phenomenally demanding—vocally, musically, emotionally—and require highly-skilled singers who specialize in this particular repertoire, to be sung convincingly.

Four of the singers seen and heard in the St. Matthew Passion are not Biblical characters at all. Rather, the dramatic action of the passion narrative halts, and these singers, functioning as spokespeople for the community of believers, step out from the chorus and deliver soliloquies—settings of contemporary, contemplative poetry--reacting to the actions taking place with personal expressions of fear, sorrow, faith. These soliloquies are set as virtuosic recitatives and da capo arias, in the style of eighteenth century baroque opera. Bach intended that these solos be sung by members of the chorus; but they are phenomenally demanding—vocally, musically, emotionally—and require highly-skilled singers who specialize in this particular repertoire, to be sung convincingly.

Four of the singers seen and heard in the St. Matthew Passion are not Biblical characters at all. Rather, the dramatic action of the passion narrative halts, and these singers, functioning as spokespeople for the community of believers, step out from the chorus and deliver soliloquies—settings of contemporary, contemplative poetry--reacting to the actions taking place with personal expressions of fear, sorrow, faith. These soliloquies are set as virtuosic recitatives and da capo arias, in the style of eighteenth century baroque opera. Bach intended that these solos be sung by members of the chorus; but they are phenomenally demanding—vocally, musically, emotionally—and require highly-skilled singers who specialize in this particular repertoire, to be sung convincingly.

Angela Young Smucker will sing the alto solos in Chicago Chorale’s production of the Passion. Chorale audiences will remember her as the alto soloist in our 2011 performance of Bach’s Mass in B minor. Angela is a Chicago-based singer, known to area audiences largely through her performances with the Haymarket Opera Company, Chicago's 17th and 18th century opera troupe. As a founding member, Ms. Smucker has appeared in productions of Handel’s Acis, Galatea e Polifemo (Galatea) and Clori, Tirsi e Fileno (Fileno); Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (Sorceress); and Charpentier’s Actéon (Hyale).

Highlights of her 2014-15 season include a recital featuring the music of Abraham Lincoln’s life; debut performances with the Chicago Bach Ensemble; performances of Handel’s Messiah with Chicago’s Bella Voce and Callipygian Players as well as the Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra; Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (Parts IV-VI) with the Bach Institute of Valparaiso University; a recital collaboration with Baroque cellist Craig Trompeter; and performances of early Polish music with the Newberry Consort.

As a concert artist, Angela has been recognized for her artistry in the repertoire of J.S. Bach: “Her discerning interpretation of the texts matched her creamy alto sonority and perceptive traversal of Bach’s serpentine vocal lines… Smucker demonstrated how astutely Bach fused such rhetoric into his music” (SanDiego.com). She has performed all of his major works, as well as numerous cantatas, and is a regular soloist with the Bach Collegium San Diego and the Bach Cantata series at Grace Lutheran Church. She has been a featured soloist under the direction of Bach scholars Helmuth Rilling and Hermann Max, and has performed at Leipzig’s St. Thomaskirche with the Leipzig Baroque Orchestra. She was also a Virginia Best Adams Master Class Fellow at the Carmel Bach Festival, has been the alto soloist for the Oregon Bach Festival Discovery Series.

Concert work from past seasons includes Mozart’s Coronation Mass (Music of the Baroque), Mendelssohn’s Elijah (Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Oregon Bach Festival), Haydn’s Creation (Oregon Bach Festival), Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience under the baton of Philip Brunelle, Mozart’s Requiem, Vivaldi’s Gloria, Handel’s Israel in Egypt and Messiah, Duruflé’s Requiem. She has been a featured artist in the U.S. premieres of Robert Kyr’s O Word of Light and Thunder (Evangelist), Francis Grier’s The Passion (Herod), and Siegfried Matthus’ Te Deum (Mezzo Soloist). Angela has also been featured on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion and WFMT’s Impromptu.

Angela’s work as a chamber artist has also earned high praise. Her debut performances with French Baroque ensemble Les Délices were chosen as a 2013 “Cleveland Favorite” by The Plain Dealer. In addition to the Bach Collegium San Diego, Newberry Consort, and Bella Voce, she has worked with Grammy-nominated ensemble Seraphic Fire, as well as the Grammy-winning Conspirare, Chicago Symphony Chorus and Oregon Bach Festival Chorus. Other choral work includes the Grant Park Music Festival Chorus, Chicago A Cappella, VocalEssence Ensemble Singers, Santa Fe Desert Chorale, Heartland Chamber Chorale, and Festival Ensemble Stuttgart.

Where do all those words come from?

A worship community could simply mount a reading of the biblical text, add a few hymns and a couple of meditations spoken by a worship leader, and be done with it. That Bach went so very much further, is his great gift to us.

Bach’s setting of the Passion According to St. Matthew was first heard on Good Friday, April 11, 1727, in Leipzig’s Thomaskirche. We twenty-first century listeners and performers must always remind ourselves that this presentation was not a concert: it was a liturgical expansion of the Vespers service, designed to recount the story of the final days of Jesus’ life, as told in chapters 26 and 27 of the Gospel of Matthew the Evangelist (in the 200-year old German translation by Martin Luther), in a manner which would make it comprehensible and meaningful to the Lutheran citizens of Leipzig. Besides the Biblical narrative, Bach set contemporary German poetry, written, adapted, and arranged by his friend and contemporary Picander (pseudonym of poet Christian Friedrich Henrici, 1700-

1764), which functioned as meditations on the Biblical text, and was intended to clarify the meaning of the story, and the motivations and reactions of the characters in the narrative, for the listeners. Presumably these meditations were to guide the understanding and private devotions of the listeners—and in this light, both Picander and Bach served the community as theologians and worship leaders. A third category of text utilized by Bach and Picander is the large number of chorale verses from the Lutheran hymnal, already well known to the listeners.

Bach sets the Biblical text largely in recitative, both secco and accompanied, in a style already familiar to his listeners from opera, especially the operas of Georg Philipp Telemann, who served as musical director for the short-lived Leipzig Opera, 1703-05. The most prominent presenter of this text, of course, is the Evangelist himself, sung by a tenor soloist; but other characters are featured as well, including Pilate, Pilate’s wife, Peter, Judas, the High Priest, a couple of maids, some witnesses testifying at Jesus’ trial—all of them sung by soloists from the ranks of the choir. The choir, sometimes as a single unit, sometimes in two opposed and conversing groups, presents the words of the disciples, the Roman centurions, the priests, and the angry crowd. These crowd scenes, called turba choruses, are not set as recitative, but rather as complex, difficult choral interjections, composed and performed with a character and style suggestive of the scene they portray.

The settings of contemporary poetry are also composed in operatic style, often as paired recitatives and arias, and usually featuring virtuosic writing for principle instruments from both orchestras. Though the actual performers are often the same singers who portray named characters in the biblical sections-- in Bach’s original conception, for instance, the tenor who sings the arias also sings the Evangelist-- these recitatives and arias are meant to be heard as the thoughts and feelings of community members, of observers, in response to

the Biblical narrative. It seems that, in Bach’s own performances, chorus members stepped forward and sang these texts, whereas the words of Peter, Judas, and, perhaps, some others, were sung by singers who were not “community members.” This practice has not, however, been followed since Bach’s own time; the arias are so demanding that specially trained soloists are engaged to sing them. Bach also composes “choral arias”: major movements which set contemplative poetry, sung by the combined vocal forces rather than by soloists.

The chorales, both music and texts, were very familiar to Bach’s listeners. Bach and Picander selected both melodies and verses carefully, to reflect the actions and attitudes being presented in their telling of the story-- so these movements have the dual role of providing comfort and familiarity to the listeners, and introducing yet more reinforcement for the overall themes of the Passion presentation. I have participated in Passion performances in which these movements were actually sung by the audience; but there is no evidence that Bach actually intended this. In some movements, Bach combines chorales, sung by the choir, with arias, sung by soloists—a hybrid procedure which functions on several interlocking levels in the telling of the story.

Odd to think about the words being more important than in the music, especially the music of Bach; but this seems to have been Bach’s own attitude and intent, in his liturgical works: to use music as a means for presenting essential text in the most immediate, dramatic, and comprehensible manner. A worship community could simply mount a reading of the biblical text, add a few hymns and a couple of meditations spoken by a worship leader, and be done with it. This is common practice in many Christian churches on Good Friday, even today. That Bach went so very much further, is his great gift to us.

Why did Bach compose his Passion According to St. Matthew?

The scope of Bach's contributions to the genre was, and is, exceptional, but the fact that he composed and mounted these productions is not: he was expected to organize some version of a passion reading, in his position as cantor of Leipzig.

In the Christian tradition, the “Passion” is the narrative, common to the four gospels, recounting Jesus’ suffering – physical and spiritual-- between the night of the Last Supper, and his crucifixion, the following day. The word itself is based upon the Latin noun passio: suffering; and shares this root with our word “patience.” Christians commemorate the Passion during Holy Week, which begins on Palm Sunday and ends the following Saturday at midnight. Following a tradition dating back to the 4th century, most Christian denominations read one or more narratives of the Passion during Holy Week, especially on Good Friday. In some congregations, these readings are communal, with one person reading the part of Christ, another reading the descriptive narrative, others reading various smaller characters, and either the choir or the congregation reading the parts of crowds and other bystanders. People began to intone (rather than simply speak) the Biblical Passion texts at least as early as the 8th century. This chanting of the text may have been freely interpretive in the beginning, but within two hundred years manuscripts began to specify exact notes to be sung. By the 13th century different singers performed specific characters in the narrative (as in the communal readings described above), a practice which became fairly universal by the 15th century, when polyphonic settings of the crowd scenes began to appear, also. By the 16th century, Passion settings had evolved into a highly developed genre, with a number of different sub-genres, composed by the prominent composers of the time. Martin Luther disapproved of the entire genre, writing, “The Passion of Christ should not be acted out in words and pretense, but in real life.” Nonetheless, sung Passion performances were common in Lutheran churches right from the beginning of the Reformation period (1517), in both Latin and German, and by the 17th century had evolved into the “oratorio passion” sub-genre, heavily influenced by the development of opera, which included instrumental accompaniment, interpolated texts, other Scripture passages, Latin motets, chorales, arias, and recitatives.

J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew and St. John Passions are the best known of this latter type. The incredible scope of his contributions to the genre was, and is, exceptional, but the fact that he composed and mounted these productions is not: certainly he was expected to organize some version of a passion reading, in his position as cantor of Leipzig. The form continued to be very popular in Germany throughout the 18th century—Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, composed over twenty settings. Interest in Passion composition waned during the 19th century, but took on new life in the 20th, with major settings by Krzysztof Penderecki, Arvo Pärt, Tan Dun, Osvaldo Golijov, Mark Alburger, and Scott King. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar and Stephen Schwartz’s Godspell contain elements of the traditional passion accounts, as well.

Oratorio’s close relative, opera, perhaps the major formal contribution of the baroque period, was well known in Lutheran Germany. Handel and Telemann, Bach’s contemporaries, were celebrated opera composers, and many German courts and cities had opera houses. The Leipzig town council, in hiring Bach, made their feelings about this modern form clear: he was instructed to “produce such compositions as are not theatrical in nature.” He was not to compose operas, and his music for divine service was not to bear any trace of operatic influence. Opera had briefly appeared in Leipzig shortly before Bach’s arrival, and the city’s response to it had ranged from skepticism to open hostility. It is clear that Bach understood the possibilities inherent in operatic styles and procedures, and that his church music compositions, especially his cantatas, had already begun to absorb characteristics of this art form; it is also clear that in composing his St. John Passion, first presented only ten months after his arrival in town, he chose to disregard the instructions he had been given, and to produce a powerfully dramatic work. Rather than just recite the words of the narrator and characters, he imbued their music with profound expressiveness, in effect creating an imaginary stage for his listeners on which the story unfolds. His later St. Matthew Passion, in which the Biblical narrative is interrupted frequently with lyrical, contemplative passages, seems to be a response to criticism from his employers that his St. John was too operatic and theatrical.

Hearing Bach's Passions

Every year, there are thousands of performances of this work. Musicians and listeners, alike, keep it alive, in expensive, imaginative, carefully researched and rehearsed presentations—and it shows no signs of wear, no signs of diminished impact or declining reputation.

Daniel Melamed begins his 2005 book, Hearing Bach’s Passions, by paraphrasing Helmuth Rilling, “who reportedly once said that it was all very well that we have original instruments and original performance practices but unfortunate that we have no original listeners.” Melamed goes on to ask, “Is it ever possible for us to hear a centuries-old piece of music as it was heard when it was composed? To put it another way, when we listen to a Bach passion, is it really the same piece Bach wrote in the early eighteenth century?” He then explores and describes the religious, social, musical facts on the ground in Leipzig and the rest of the Lutheran, German-speaking world during Bach’s time, effectively making his case that Bach’s “Great” Passion According to St. Matthew, in its original context, nearly 300 years ago, is indeed not at all the work we hear in concerts today, and that no amount of care for “authenticity” in our preparations for such a performance can change that fact. Bach’s listeners were intimately familiar with much of what they heard in the Passion’s three hours of music. The wealth of hymn tunes (and texts) which serve as the musical and theological foundation of the work, also served as the foundation of German Lutheran religious practice; almost surely, every person in attendance on Good Friday knew each note and word, by heart, and felt “at home” and comfortable when these hymns were sung. Bach’s musical language, though somewhat more complex and difficult than that of his contemporaries, did not come as a bewildering surprise to his parishioners—they experienced it every Sunday, year in and year out, in the cantatas he regularly presented during weekly worship. His performers played, and sang, on instruments, and in a style, which were the everyday norm; no one had to accept sounds or expressions which were outside their normal experience. Though the words of the Evangelist and the chorales were in a somewhat archaic German, it was still a German which the listeners understood; and the arias were settings of contemporary German poetry. All of the listeners were officially and legally Lutheran, and subscribed to the theology Bach presented; I suspect they participated in annual presentations of the Passion narrative worshipfully and unquestioningly. Twenty-first century listeners might find the work’s length daunting, but this was nothing to his original hearers: they also sat through a two hour sermon inserted between parts one and two, plus a number of motets and prayers, and endured all of this in an unheated church.

Modern audiences, on the other hand, approach these inescapable aspects of Bach’s work from a tremendous distance, and would seemingly face an impossible task in overcoming this distance; to properly appreciate Bach’s accomplishment, one would think, they would need to take on a special, informed persona, an impossible task. Altogether, our current experience of Bach’s Matthew Passion is, as Melamed and Rilling suggest, irrevocably removed from the experience of Bach’s original listeners.

So why present it?

Well, the fact is, we do. People want to hear it. Every year, throughout the world, there are thousands of performances of this work-- and these performances are far more than dutiful recitations of a hoary museum piece of which we are all told to be in awe. Musicians and listeners, alike, keep it alive, year after year, in expensive, imaginative, carefully researched and rehearsed presentations—and it shows no signs of wear, no signs of diminished impact or declining reputation. Despite changing musical tastes, religious constructs, linguistic traditions, technological developments, performance styles—aspects of our material and intellectual culture which come and go with increasing rapidity-- Bach’s Great Passion shines like a beacon over all, strikes fire in some universal human heart, touches and releases some universal soul.

Chicago Chorale’s production will reflect our own “realities on the ground”: the membership of our ensemble, our performance venue, the soloists and instrumentalists available to us, the amount of money we have to spend on our production, the expectations we have of our audience. On the most basic, material level, it will be Chorale’s take on Bach’s Great Passion, not Leipzig’s. But I am confident that the core value of the work will shine through for us and for our audience, as it did for Bach and his listeners. This music is that big.

Onward and upward

Every musician I know, who has lived with Bach's Matthew Passion, has in some respect been broken, shattered, and remade through the experience.

I fervently wish a happy new year for all of us, an increase in joy and prosperity, a lessening of pain, sorrow, and hardship. Here’s hoping that the coming year brings with it the compassion, the expanded understanding, the mercy, joy, and peace, about which we sing in so much of our music. Next Wednesday, Chicago Chorale begins rehearsing J.S. Bach’s Passion According to St. Matthew, which we will present on Sunday, March 29, at Rockefeller Memorial Chapel. This work is not new to Chorale: we performed it in March, 2008, at Chicago’s Church of the Holy Family; and I have sung it, personally, on several occasions. But it will be new to many of our singers and instrumentalists; and, effectively, it is new each time one performs it-- a piece so large, so rich and multi-faceted, yields new secrets, new complications, new insights, each time one approaches it. The sheer size and scope of it guarantees that any production of it will challenge us and require our utmost concentration and commitment.

I last sang in a production of the Matthew Passion six years ago, just months after conducting it myself, at the Oregon Bach Festival, under the leadership of Helmuth Rilling. Mr. Rilling knows the work, as scholar and as performer, as well as anyone on the planet; he has written and lectured extensively on it, and has conducted it hundreds of time, which he does entirely from memory—an incredible feat. In this particular performance, we had nearly reached the end, when his memory and concentration slipped, and he miscued the tenor singing the Evangelist role, and the continuo players supporting him. It was a small thing, almost surely unnoticed by the audience; to the Evangelist and the continuo players, however, as well as to the rest of us on stage who were following in our scores, it seemed enormous; after nearly three hours of the most intense concentration and involvement, we were living every note, every word, every gesture, along with Mr. Rilling. It felt as though he, and the rest of us, had approached the holy of holies, and had stumbled at the last moment, on the top step. After the applause and curtain calls, he retreated to his favorite place, outside the stage door, and lit up his accustomed cigar; it was clear he did not want to be approached by anyone except his family and closest friends. I walked by, keeping my distance, when he called out to me—“You—you know the mountains and valleys of this piece.” That was all. I was embarrassed; I thanked him for enabling me, and us, to be owned once again by this incredible work, then moved out of range.

This experience illustrates, for me, the essential, terrifying, humbling truth about this work: Bach’s Matthew Passion is indeed the holy of holies, the most comprehensive and influential single work of musical and dramatic art, reaching past the Western musical canon and the particulars of the Christian faith to describe, through music of unbearable beauty and power, the essentially tragic nature of our human condition. None of us can know it, can encompass it, can claim it as our exclusive property, can in any respect conquer it. Every musician I know, who has lived with this work, has in some respect been broken, shattered, and remade through the experience. Its mountains and valleys are the human condition, the life we lead on this earth. How this incredible vision, in all its complexity, can have been transmitted to us through the medium of the Cantor of Leipzig, has been the subject of countless books, articles, sermons, lectures, pronouncements; Bach’s legacy, indeed, “boggles the mind.” Chorale will endeavor, over the coming months, to come to an informed grip on both this legacy, and on the music which inspires it. I hope you will join us—both in exploring this legacy, and in experiencing our performance, on March 29.

Solemn Vespers for the Third Sunday in Advent—on Saturday!

The monastery’s beautiful chapel is an acoustic gem—one of the really sublime spaces to hear choral music in the city.

Almost since our founding, back in 2001, Chicago Chorale has sung in various liturgies and concerts at Monastery of the Holy Cross, at the corner of 31st Street and Aberdeen, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. The monastery’s beautiful chapel is an acoustic gem—one of the really sublime spaces to hear choral music in the city. The Benedictine monks who live there, take full advantage of this beauty, chanting appropriate psalms and liturgies several times a day, day in, day out, throughout the church year. Their prior, Father Peter, was, in a former life, a University of Chicago undergrad, who majored in music and participated fully in the musical opportunities the University had to offer; and he has carried his love of good music, his erudition in selecting and performing it, and his skill in teaching others to perform it, into his life in the Monastery.

Some years ago, Father Peter and I settled upon a model for a choral advent service, very different from most such services in the city. Completely eschewing the warm, somewhat sentimental approach of most such services (which tend to focus more on the actual Christmas event, the birth of Jesus, rather than upon the period leading up to the birth), Father Peter strictly follows the texts and rubrics for the season, acknowledging the historical character of Advent as “a little Lent”—a time for reflection and self-examination, for acknowledgment of our darkness and of our yearning for enlightenment and salvation. He adapts the Solemn Vespers liturgy to the season, retaining the elements that are part of every Vespers service, every day—the Magnificat, the Pater noster, the chanting of psalms-- and then enriches this framework with the addition of polyphonic settings of such hymns as Alma Redemptoris Mater and Conditor alme siderum, and appropriate motets ( this year, Ecce Domins veniet).

Almost since our founding, back in 2001, Chicago Chorale has sung in various liturgies and concerts at Monastery of the Holy Cross, at the corner of 31st Street and Aberdeen, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. The monastery’s beautiful chapel is an acoustic gem—one of the really sublime spaces to hear choral music in the city. The Benedictine monks who live there, take full advantage of this beauty, chanting appropriate psalms and liturgies several times a day, day in, day out, throughout the church year. Their prior, Father Peter, was, in a former life, a University of Chicago undergrad, who majored in music and participated fully in the musical opportunities the University had to offer; and he has carried his love of good music, his erudition in selecting and performing it, and his skill in teaching others to perform it, into his life in the Monastery.

Some years ago, Father Peter and I settled upon a model for a choral advent service, very different from most such services in the city. Completely eschewing the warm, somewhat sentimental approach of most such services (which tend to focus more on the actual Christmas event, the birth of Jesus, rather than upon the period leading up to the birth), Father Peter strictly follows the texts and rubrics for the season, acknowledging the historical character of Advent as “a little Lent”—a time for reflection and self-examination, for acknowledgment of our darkness and of our yearning for enlightenment and salvation. He adapts the Solemn Vespers liturgy to the season, retaining the elements that are part of every Vespers service, every day—the Magnificat, the Pater noster, the chanting of psalms-- and then enriches this framework with the addition of polyphonic settings of such hymns as Alma Redemptoris Mater and Conditor alme siderum, and appropriate motets ( this year, Ecce Domins veniet).

The monastery’s chapel is particularly suited to polyphonic, unaccompanied music, performed by a smaller group of light, clear voices—so each year I choose a subset of Chorale’s singers who are particularly adept at this repertoire, and enthusiastic about the disciplines that go into performing it. Father Peter is interested in the historic background of Roman Catholic music, and in experiencing it in its appropriate role as liturgical, rather than concert, music. Each year, we explore the liturgical music of a particular composer—music one would usually hear in concerts by groups which specialize in renaissance music, but less and less in actual liturgical practice. This year’s composer, Tomás Luis de Victoria, was the most famous composer in 16th-century Spain, and one of the most important composers of his era. He studied in Rome with Palestrina; but his music has a brooding, emotional quality very different from that of his teacher, and appeals viscerally to modern listeners in a way Palestrina’s sometimes doesn’t. Many singers claim Victoria as their favorite renaissance composer: not only does he write beautiful lines which combine in beautiful harmonies, but he appeals to the heart and the feelings.

If you are free at 5 PM this Saturday afternoon, December 13, come and experience this beautiful service in this beautiful space. We request a donation of $15, but are happy for anything you can give; mostly, we want to you come and hear us, to step into a world of peace, quiet, and stillness and let all the elements of this Vespers service have their way with you.

Saturday, December 13, 5 PM, Monastery of the Holy Cross, 3111 South Aberdeen Street.

Mozart wrap up

Chorale’s rousing success with Mozart’s Mass in C minor says many things about our group.

Chorale’s rousing success with Mozart’s Mass in C minor says many things about our group. First: our unwavering faith in our ability to handle the finest music available to us, though it seems at times preposterous, actually enables us to rise to the occasion, accomplish the musical and linguistic requirements presented by the task before us, at a level few of us would be able to accomplish on our own. We have learned, over the years, that organized hard work toward a worthy goal is a powerful motivator. Chorale’s singers start out expecting, even demanding, the right to learn and present great music; but that can be a pretty nebulous goal, until put to the test. Our singers tend not to waver and fold when truth smacks them in the face; rather, they are energized by the demands of the task before them, and expand, joyfully, to fill whatever shoes need filling. This is simply the character of the singers who constitute our ensemble; every conductor should be as lucky as I am, to have such personalities in his choir.

Second: there really is an audience out there, for the sort of music Chorale chooses to present. Chicago is a big city, and the task of contacting, and attracting, those who love great music, can be daunting; but the size, and palpable enthusiasm, of the audience who heard us in Orchestra Hall—the place was packed!-- convinces us that we are on to something, in our repertoire focus. These people love Mozart. It is so important to me, and to the group, to know that we are on the right track, in programming such repertoire. Chorale has to learn better how to market ourselves, in order to get these same music lovers to come again and again to hear us; but we have now seen about 2,500 of them, we know they are out there, and they have heard us.

Third: our demanding, never-ending search for appropriate collaborators pays off. We thoroughly enjoyed working with Civic Orchestra of Chicago, and felt pushed by their standard, to raise our own; and in Nicholas Kraemer we found a conductor who could really appreciate our musical values and ideals, guide us in making sense of the music on the page, and help us put it all together in a finished performance. His musical ideas, honed by many years of working with first class chamber and period ensembles, both as player and as conductor, matched very well with Chorale’s disciplines and goals; effectively, he spoke a language we had already studied, and he hastened our learning. We were never confused by him; he wanted what we wanted, and he taught us to want it at a higher level.

Finally: we had so much fun! Doing great music to the best of our ability is fun. The tension and stress of getting to that level, though palpable in rehearsals, melts away once we get in front of an audience. The greater the challenge, the higher the level of our performance, surely; but also, the higher the level of our enjoyment! Doing great music well, is a sublime joy.

Iron fist in a velvet glove

Our Mozart Mass in C minor now belongs to Nicholas Kraemer. Please come and hear what he does with it!

Chorale’s first rehearsal with Nicholas Kraemer was very exhilarating and exciting. The singers were prepared, and on their best behavior: they arrived on time, they uncrossed their legs and sat up straight, they watched the conductor, they shone with enthusiasm. This must have been very gratifying for Mr. Kraemer—he had just arrived from London, and announced his jet lag, apologizing in advance for any shortness of temper he might display (there was none). Throughout the afternoon, watching and listening to Mr. Kraemer rehearse, I repeatedly thought of a phrase I first heard in a master class with soprano Elly Ameling and pianist Dalton Baldwin, more than thirty years ago: “iron fist in a velvet glove.” Referring specifically to a song by Gabriel Fauré, Ms. Ameling warned a singer not to give into his feelings, to his romantic impulses, but to submit them to the rule of the tempo, the pulse. She told us that the truth of Fauré’s musical language lies in the tension between these two poles: the unwavering firmness of his forward movement, and the emotion expressed through his harmonies and melodies.

I often use this phrase, and principle, when rehearsing Chorale. We all feel the beauty and emotional satisfaction inherent in the music we perform; but we can’t afford to skip, or even skimp on, establishing what I call “the grid”: the pitches, up and down, and the rhythms, from here to there. Chorale members spend an amazing amount of time nailing down pitches and rhythms, both on their own time and in group rehearsal. I do my best to let nothing slide, to correct every error, to clarify each rhythmic subdivision—I always imagine some bright music student taking dictation, and try to produce something he can hear and transcribe. I remember very well a phrase Harry Keuper used in describing Robert Shaw’s nagging perfectionism: “toilet trained at the point of a gun;” and I wonder if my singers say something similar, of me.

To some extent, I have become this way out of a desire to overcome my own unbridled feelings and impulses when enjoying music. Elly Ameling was speaking to me; and years of studying and performing with Dalton Baldwin, Robert Shaw, and Helmuth Rilling have developed a hyper-awareness in me of the many ways there are to indulge oneself and get off track. But I also realize on my own, that when a large group of singers gets together, they can very easily become an amoeba, spreading formlessly all over the place and leaving structure and coherence behind, no matter how much they love what they are doing, no matter how good they feel about themselves. Yet I am on guard that I not suppress the wit, style, and life of the music-- the velvet glove-- in order to keep the amoeba corralled. Fauré’s music needs work with a metronome; it also needs acknowledgement and nurturing of its silk and velvet soul.

As does Mozart's. Just a couple of weeks ago, I said to Chorale, “I am trying hard to balance the iron fist with the velvet glove, trying to make the most efficient choices, in preparing you for what Mr. Kraemer will bring to this performance.” And when push came to shove, I chose the fist. The grid. During our conductor’s piano rehearsal, I witnessed Mr. Kraemer slide his velvet glove onto the fist I had prepared, listened to him smooth the rougher edges, sand down the sharper articulations, enliven the gnarlier passages over which we had slaved in establishing clarity—and I was envious. I wanted to enjoy, myself, breathing life and style into this music, stroking its velvet surface. So much like losing control of your child as she goes off into the world, hoping you have chosen to emphasize the right lessons, established the iron fist within but at least hinted at the promise, the beauty, of that velvet glove.

Our Mozart Mass in C minor now belongs to Nicholas Kraemer. Please come and hear what he does with it!

Mozart's Unfinished Mass

Two important questions hang over any consideration of Mozart’s Mass in C minor: how did it come to have so huge a design—so very different from his other masses; and why didn’t he finish it?

Two important questions hang over any consideration of Mozart’s Mass in C minor: how did it come to have so huge a design—so very different from his other masses; and why didn’t he finish it? Prior to 1781, Mozart had been court organist and concertmaster, assisting his father Leopold, who served as deputy Kapellmeister for the Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, Hieronymous Colloredo. In this capacity, Mozart composed a number of settings of the mass for liturgical performance at the Salzburg Cathedral. The Austro-Hungarian Emperor Joseph II sought to reform the Catholic mass service, and called for sacred music with short and relatively unadorned choral passages, no aria-like solos, and no choral fugues. Colloredo followed the emperor’s lead, requiring that a mass not exceed forty-five minutes in length; as a result, Mozart's mass settings for Salzburg are relatively short, and most are not awfully interesting. For this and many other reasons, Mozart felt exploited and imprisoned, and sought every opportunity to leave Salzburg. Finally, in May of 1781, he left the archbishop’s service and moved permanently to Vienna, embarking on a career as a freelance composer. His rejection of the secure life of Kapellmeister chosen for him by his father, together with his courtship of the young soprano Constanze Weber, of whom his father disapproved, caused a rift between father and son which was never really healed; when Wolfgang and Constanze were married, in August 1782, it was without Leopold’s presence or blessing.

Shortly after Mozart's arrival in Vienna in 1781, he met Baron Gottfried van Swieten, a patron of the arts who actively promoted the music of past masters such as Handel and J.S. Bach. He owned a copy of the complete score of Bach's Mass in B minor, probably obtained from Bach's son Carl Philip Emmanuel. It is suggested that Mozart composed his Mass in C minor in reaction to his exposure to this work, and to Bach and Handel in general. He adopts the Italian, “cantata-style” structure of Bach’s Mass, dividing the texts of the five mass sections into smaller movements, each of which stands on its own, as opposed to the "through-composed" style where the entire text is sung from start to finish, without a break. Movements often alternate between elaborate contrapuntal choral settings and operatic arias for one or more soloists. The style was more operatic and theatrical than that allowed by the Emperor and the Prince-Archbishop, and resulted in a far longer mass than was allowed. Mozart imitates Handel's dotted, French overture rhythms (the signal in Baroque France for the arrival of the king) in texts addressing the King of Kings. Mozart's Mass in C minor and Bach's Mass in B minor both have an impractical combination of choral voicings, with five-part choir for modern-style choral writing, four-part choir for fugal movements, and double choir for the Osanna The orchestral layout is similarly impractical, each work containing a solo instrument that sits quietly for an hour before accompanying a single aria. Mozart's setting has a number of movements where the bass section descends, half step by half step, over the distance of a fourth, as does the Credo movement in Bach’s Mass. And the fugues are among Mozart's first efforts to compose counterpoint with anything like Bachian complexity. In discovering and reacting to Bach and Handel, Mozart adopts the grandness of their conception, leaving behind forever the relative modesty and self-effacement previously forced upon him by circumstances in Salzburg.

There is no evidence that Mozart received a commission to compose his Mass, and it is not clear why he decided to do so. He mentions the work once in a letter to his father, in which he promises a mass if he can bring his wife Constanze home to Salzburg to meet her husband’s family. It has been suggested that this Mass may have been intended as a peace offering to Mozart’s father, as an act of thanksgiving for the birth of his first child, and as an opportunity to show off his wife’s talent (she sang one of the soprano solos at the work's one and only performance). Constanze herself recalled that he promised to write a mass after her recovery from the birth of their first child.

Wolfgang and Constanze arrived in Salzburg at the end of July, 1783, with only half of the work completed: the Kyrie and Gloria movements. Once in Salzburg, he worked on the first half of the Credo and the Sanctus. Some movements are not complete in copies that have come down to us, but a number of scholars have reconstructed them. Mozart never composed music for the second half of the Credo or any of the Agnus Dei. The Mass in C minor was performed in St. Peter’s Benedictine Abbey, just outside of Salzburg (and marginally outside the jurisdiction of the Prince-Archbishop) on Sunday, October 26, 1783, in a liturgical setting; presumably the missing movements were replaced with movements from Mozart’s earlier masses, or with plainchant.

And that was the end. Mozart never returned to his Mass, except to adapt some of its music for another work, Davide Penitente, in later years. Like Bach’s Mass in B minor, which preceded it, and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, which followed it, the Mass in C minor would, if completed, have been far too long for practical liturgical use; one has to assume that Mozart was too busy and pressed to devote time to completing a work which stood little chance of being performed. Unlike the other two composers, Mozart became more and more committed to opera, which took up much of his time and attention for the remaining years of his career.

Great music, done well-- by and for whom?

Last night‘s Mass in C minor rehearsal was absolutely thrilling for me-- Chorale’s singers get it, and I know our audience will get it, too, when they hear our November 24 concert.

When Chicago Chorale first sang together, in October 2001, all of its members were University of Chicago students or alums. And I am fairly certain that the audiences who first heard us were composed entirely of Hyde Parkers, most with U of C connections. Though we continue to rehearse in Hyde Park, U of C’s home turf, the actual percentage of those with University affiliation has slipped since then; currently, about sixty percent have some formal connection with U of C. And we now present at least half of our concerts outside of Hyde Park, attracting a regional, rather than purely local, audience. But I think Chorale’s style, habits, expectations, continue to reflect its roots. From the beginning, our singers have tended to be highly intelligent and educated; they have experience with a broad range of musical styles, and prefer the rigorous, erudite programming which has become our trademark; they attend concerts, listen to recordings, read reviews and scholarship, and are generally very informed, about music and about arts culture in general. They read extensively, write well, think critically, and question nearly everything. Not a week goes by, that I am not stopped after rehearsal, or do not receive at least one email, with a comment, suggestion, question, clarification, about something I have said or done during rehearsal. The singers pay close attention to my verbal communications, oral and written, and on occasion correct me, pick at my grammar, argue with me. I am continually reminded that they really listen to me, that I must be careful, be on top of things, mean what I say, have supporting information, avoid platitudes and generalities. And I often need a thicker skin to face their probing, informed questions and remarks, than l expect.

Chorale singers expect to perform on a high level. They are in general confident, disciplined, and determined to succeed. They demonstrate little fear or hesitation when tackling really challenging repertoire—rather, they revel in being challenged. Their general, incoming level of vocalism and music-making is respectable and competitive; what sets them, and Chorale, apart, thought, is the richness of understanding and experience with which they approach their craft, and the high level of appreciation they experience in practicing it. It is the general character of choral performance, that the sum is greater than the parts; with Chorale, this characteristic takes on new and urgent meaning. Altogether, Chorale is a very different group than I have ever sung with or conducted in other places, at other times. New singers are either drawn specifically to this character of the group, or they learn to appreciate and value it.