The Second Time Around

I find great pleasure in returning to Shchedrin’s work, which we studied so intensely, as a previously unknown composition, back in 2012.

The Second Time Around—I remember that phrase as a song title from the 1960’s—“Love is lovelier the second time around…” Frank Sinatra and other singers of that era recorded it, and it seemed to be on the radio constantly—at least, on the stations my parents listened to. It has become an occasional ear worm as Chorale rehearses Shchedrin’s The Sealed Angel, not because it sounds like Shchedrin’s music, but because of the pleasure I find in returning to Shchedrin’s work, which we studied so intensely, as a previously unknown composition, back in 2012. In general, my feeling about repeating a work is, if it isn’t worth repeating, it wasn’t worth doing in the first place. If I don’t grow, and feel differently the second time around, either I am becoming stale, or the piece is akin to the shallow soil in the parable of the sower—the seeds come up quickly, but can’t withstand the heat or the drought. The Sealed Angel is good soil. Back then, it was really daunting for me to make sense of it—to find structure, guideposts, and to find the best way to conduct it. The score is bewildering—as I wrote last week, Shchedrin cares little for regularity or consistency; he writes down what he likes, and then may write something different in what one would expect to be a parallel place, the next time around, because he feels differently, and wants something else instead. I struggled to “get inside his head,” to feel and understand the motivation behind the changes and the nuances which constantly tripped me up when I first approached the work, to discover the overall sweep and direction of the piece. I find now, six years later, that I have internalized what I learned back then, and am far more comfortable with the work, and with Shchedrin’s idiom. My score—the same one I used then—is full of markings, of rhythmic groupings, of “eyeglasses” and other warning signs; and most of these are still “right”: I feel now as I felt then, and can make use of many of the decisions I made then. Some groupings and phrases change, and my understanding of dynamics has been somewhat refined, as I work with a different group of singers (one size really does not fit all)—but mostly I feel right at home. I am comfortable enough to feel less constrained by some of what he has written—his instructions are vague, even contradictory, and I agonized over this six years ago, fearful of doing the work injustice. I feel less constrained now. Numerous recordings which have come out since testify to the need for each conductor, each ensemble, to take its own stance relative to what Shchedrin calls “ 50 percent stupidity”—to find, and go with, what works. Steeped as I am in the tradition of J.S. Bach, I found it very difficult to just take off and do as I felt (exactly as Shchedrin himself does)—but I feel bolder, now.

Chorale has sung a lot of Old Church Slavonic since 2012—major works by Rachmaninoff and Steinberg, plus a number of smaller pieces by Chesnokov, Grechaninov, and Golovanov. Our singers are more familiar and comfortable with the sounds of the language than they were in 2012; and though the transliteration system used in the Shchedrin score is far different than that used by the editors of those other works, we recognize the equivalents, and learn quickly. Our language coach, Drew Boshardy, has become adept at working with us, at anticipating our difficulties and focusing on them, which is also a big help. And the singers are more familiar with the overall vocal approach required by the music-- so different from the lighter sound required by much of what we sing.

This relative comfort—on my part, on the choir’s part—allows, even invites, more freedom, and more enjoyment, in preparing the music. Time seems to fly by, in our rehearsals. We hope you’ll come to hear us, whether you heard us the first time around or not—find out for yourselves that this music is lovelier the second time around.

An Image That Fits The Music: A Guest Blog Post by Managing Director Megan Balderston

One of my unexpected “favorite” things about being Managing Director of Chicago Chorale is that of being the brand ambassador, which is a fancy way to say that I get to work closely with our graphic designer to pick the images around our concert and brochure artwork. Over the years this has turned into a labor of love for Artistic Director Bruce Tammen and me, who are often the final decision makers for our concert artwork.

I am certain we are not the easiest people to work with. For a recent concert, the direction I gave our intrepid graphic designer, Arlene Harting-Josue, was: “Can we come up with some abstract image that presents these concepts: something upwards and onwards. Something perhaps joyous, but seriously so. Not whimsical, not antique; but something fresh and modern and inviting.” Somehow Arlene can sift through this and give us some great ideas. And we know what we like when we see it.

One of my unexpected “favorite” things about being Managing Director of Chicago Chorale is that of being the brand ambassador, which is a fancy way to say that I get to work closely with our graphic designer to pick the images around our concert and brochure artwork. Over the years this has turned into a labor of love for Artistic Director Bruce Tammen and me, who are often the final decision makers for our concert artwork.

I am certain we are not the easiest people to work with. For a recent concert, the direction I gave our intrepid graphic designer, Arlene Harting-Josue, was: “Can we come up with some abstract image that presents these concepts: something upwards and onwards. Something perhaps joyous, but seriously so. Not whimsical, not antique; but something fresh and modern and inviting.” Somehow Arlene can sift through this and give us some great ideas. And we know what we like when we see it.

The imagery for this concert was, therefore, a surprise. The Mozart Requiem is so iconic a piece, and despite the sadness of its subject matter, is not entirely sad. It is enshrouded in mystery. By its very unfinished nature, one always wonders what would have been, had Mozart lived to truly complete it. (See Bruce’s blog post about the Robert Levin completion we are using.)

Still, I was a bit surprised how the concert artwork affected our choir members when we presented it to them. For Bruce and me, the photograph was hands down our favorite in the mood it conveyed, and we didn’t ask about it. But the choir came back with: “What is the story of this image?” and “This image: I find it beautiful but it disturbs me, at the same time.” They asked me to go back to the photographer, Javier de la Torre, and find the story behind the photograph. Here is what he says:

“This pier is located in a really old fishing village called Carrasqueira, in the Alentejo area, close to Lisbon, Portugal. The piers have traditionally been maintained by the fishermen, but this particular pier is abandoned and no maintenance is done, so, nowadays, it doesn’t exist.

This shot was taken in 2010, and 3 years later, in 2013, I returned to Carrasqueira, but the pier was almost destroyed. Last December a great storm finally destroyed it totally, so, this shot cannot be repeated anymore.”

Knowing the story makes me appreciate our instinctive choice of the photo even more. For my part, I felt that the visual representation of the unknown structure of the pier beneath the surface, as well as the beauty of the colors, made for a striking and memorable image. Like music performed live, the photographer captured a moment in time that will never again be replicated. And Bruce? He says, “The feel of the image looks to me like the sound of the Lacrimosa movement.”

Interesting, ephemeral, and beautiful: much like Mozart’s music and his legacy.

Sisu: Part 2

Guest post by Managing Director Megan Balderston

Those of you who have read Bruce’s Blog over the years may recall his December, 2010 blog about the Finnish word, “sisu.” http://www.chicagochorale.org/sisu-and-chicago-chorale/

At a recent rehearsal for a musical I performed in, after failing once again at a particular dance pattern that was coming naturally and effortlessly to only about two people, my friend looked at me and groaned, “Why do we come here night after night, just to be yelled at because we can’t do this correctly?” The truth is, many of us who have a love of musical theater will never come even close to being Sutton Foster. Why do we do it, then? I have been thinking about that very question, quite a bit, as it relates to all of my various avocations and hobbies. They have this question in common.

There are a number of Chorale singers who are involved with the sport CrossFit, and I am one of them. I regularly attend our gym’s 6:00 am class, which right now is made up mostly of people my own age. If you don’t know (and I’m not sure how you don’t, as we CrossFitters have a reputation of talking about the sport ad nauseum) CrossFit gyms are notoriously spartan. No spas, no mirrors, just equipment and mats. Our class is small but mighty, average age is 50, and we have the following in common: a love for 80’s music; we may not like the individual exercises, but we like the way they make us feel; we believe in building on our strengths and trying to develop our weaknesses; and the camaraderie helps. In fact, one day as Bruce and I were chatting about it, he remarked, “It sounds absolutely miserable but they know how to build a program so that you all have fun.” Indeed, painted on the wall of our gym is the following list: 1. Check your ego at the door. 2. Show up and do the work. 3. Nobody cares what your time is. 4. Everybody cares if you cheated. 5. Effort gains respect.

What do these disparate activities have to do with choral singing, and each other, let alone the concept of sisu? Quite a bit, as it turns out: they all have the common theme of "deciding on a course of action and then sticking to it despite repeated failures."

Two weeks ago I was attempting to get a “PR” (personal record) on a back squat: this is a lift where you place a barbell across your shoulders, lower into a squat, and then press back up so that you are standing upright. As a novice to intermediate level lifter, I was thrilled to increase my “PR” by 5 pounds. So I thought, why not add another 10 pounds and see how I do? Alas, I could not stand up again; I got stuck “in the hole” at the bottom of the squat. This is a bit humiliating. However, one of my gym buddies reminded me: you can’t improve, if you don’t first attempt more and fail.

Choral singing, the way Chicago Chorale does it, is also about this kind of mindset. I suppose we could pick easier repertoire, or a less rigorous schedule, or do any number of things differently so that we wouldn’t be presenting concerts that require so much effort. So much grit. So much sisu. But I believe that would take away exactly the kind of determination that makes Chorale a special group within the landscape of Chicago’s many musical groups, both amateur and professional. We care so much, and if we have to white-knuckle some things, and demand more out of ourselves to present a beautiful program, that is where we would rather be.

Do I love failing? Noooo, that’s not it. But I do find that I love the process of learning something new, and showing myself that I can do things I never dreamed I could. I probably strangely love the cycle of repetition, humiliation, exaltation, despair, laughter, and renewed confidence. Bruce sent a note around to the choir this week, in which he said the following: "I want us to be clear-eyed, clear-eared, objective, self-critical, idealistic; I want us to be, and do, the very best that is in us."

I’m with Bruce. As a 48-year-old woman I do not need to lift weights, to float a high F, to tap dance, or to open myself up to scrutiny and possible humiliation by putting myself on the line in any number of ways. And yet I think of all of the wonderful things I would be missing if I did not: it would be a quieter, and less joyful life. We all owe it to ourselves to explore what is the best in us, whether or not we will become the best in the world. Effort gains respect, for sure, but more importantly effort gains self-respect. Sisu. The determination required for the journey is as special as the end product. I hope you will join us when we present our concert on June 10th, and hear what "sisu" sounds like.

Choral Music in the Driftless Area

The Lutheran college choral music tradition is not the only viable choral tradition at work in American today; but it is certainly one of the most notable, thanks in no small part to the tireless efforts and indefatigable spirit of Weston Noble.

Last weekend I drove about five hours northwest of Chicago, into the Driftless Area. This region, where Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin converge, was, mysteriously, not covered during the most recent ice age, and has a very different geographic character than the glacier-scoured lands surrounding it-- limestone bluffs, deep valleys, pine and hardwood forests, cold water caves and trout streams, all of it bisected by the Mississippi River and its tributaries, which cut the land into small, enclosed, isolated patches of prairie and forest. Farming here is a beautiful challenge-- the farms are small, and made up of irregularly-shaped pastures and tilled fields, gracefully terraced and contoured to prevent the topsoil from washing down to the Mississippi, and separated from one another by woods and stone outcroppings. Family farms are the norm, with dairy, hogs, sheep, orchards, vineyards, and the usual Midwestern crops of hay, corn, and soybeans—again, in small patches, rather than the enormous, horizon-to-horizon agribusiness plantings one finds in the prairieland in all directions surrounding the area. It is an area of great natural beauty, both subtle and dramatic, where humans have been inspired to fit in with that beauty, rather than subdue it. My Norwegian ancestors settled in this region in the 1860s; my great-great-grandfather, Ove Jacob Hjort, his two wives, and many of his children are buried in the cemetery at East Paint Creek Lutheran Church, one of several parishes he served, high on a ridge near Lansing, Iowa. He, and several other state church pastors, came from Norway to serve the needs of the Norwegian settlers who had settled in the area, in the midst of settlers from Bohemia, Ireland, and New England-- people from whom they were separated by language, religion, and cultural habits. The church had been the center of community and culture in their isolated settlements back in Norway; and they relied on this pattern in their new home, as well, depending on their pastors to lead them, to interpret their new experience, and to hold them together in their ethnic communities.

It happens that communal singing was an important trait of the Norwegians. I assume it was a koselig sort of thing to do, to gather in homes or in church on dark winter nights, share food and drink, and sing—both sacred psalms and secular folk-songs. Communities would probably have a pastor who was also a schoolteacher and a musician, and who might lead songs from a reed organ. The people tended to be remarkably literate, and read music as well as words. Accounts of my ancestor invariably refer to his rich singing voice; never to his preaching. This habit of singing together took root in the Driftless Area, as well as in other locales, and became emblematic of the lives of Norwegian immigrants and their descendants in the new world. The settlers quickly began founding schools, colleges, and seminaries; and choral singing was an important part of the experience these institutions provided. The schools promoted their choirs, sent them on mission trips to isolated parishes, relied upon them to recruit new students. The choral conductor was an important member of the faculty, teaching general music courses as well as conducting, and embodying the institution’s mission to its constituency.

Back to last weekend: I visited my Alma Mater, Luther College, in Decorah, Iowa (right in the middle of the Driftless Area) to participate in memorial observances marking the death, last December, of the college’s most famous and long-lived choral conductor, Weston Noble. Though neither a Norwegian nor a Lutheran (his background was Yankee Methodist), Weston embodied, and tirelessly promoted, the ideals I have described: communities should sing; they should sing well; they should sing to the glory of God, and to promote their communal sense of identity. Not least of all, the choral leader should be as much pastor and teacher, as conductor. During the fifty-seven years he served Luther College, Weston brought substantive growth and change to his community, and led it through the immigrant identity into the modern, American musical world; he promoted a framework for communal singing, passed down through his generations of students, which I expect will continue unabated, despite cultural changes and influences which might otherwise cause it to wither away. The Lutheran college choral music tradition is not the only viable choral tradition at work in American today; but it is certainly one of the most notable, thanks in no small part to the tireless efforts and indefatigable spirit of Weston Noble.

Back to last weekend: I visited my Alma Mater, Luther College, in Decorah, Iowa (right in the middle of the Driftless Area) to participate in memorial observances marking the death, last December, of the college’s most famous and long-lived choral conductor, Weston Noble. Though neither a Norwegian nor a Lutheran (his background was Yankee Methodist), Weston embodied, and tirelessly promoted, the ideals I have described: communities should sing; they should sing well; they should sing to the glory of God, and to promote their communal sense of identity. Not least of all, the choral leader should be as much pastor and teacher, as conductor. During the fifty-seven years he served Luther College, Weston brought substantive growth and change to his community, and led it through the immigrant identity into the modern, American musical world; he promoted a framework for communal singing, passed down through his generations of students, which I expect will continue unabated, despite cultural changes and influences which might otherwise cause it to wither away. The Lutheran college choral music tradition is not the only viable choral tradition at work in American today; but it is certainly one of the most notable, thanks in no small part to the tireless efforts and indefatigable spirit of Weston Noble.

Palestrina: The "Savior of Music"?

Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

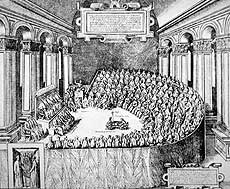

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the  increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

It seems unlikely that the Pope Marcellus Mass was composed with the intent of saving music, or even that Palestrina’s name, career, and music came up in the Council’s discussions. No documentation exists to support such a role for him. Most likely, he was a career church musician who was willing to make a few minor adjustments to fit certain requirements because it was the sensible thing to do. Nonetheless, beginning almost immediately in 1564, Palestrina became “the savior of music,” and remained so through the later twentieth century. The Roman Catholic Church presented his compositional style as a model for good church music, and generations of music students studied his works, particularly this mass, as an example of what they should understand and emulate. Giuseppe Verdi said of the composer, “He is the real king of sacred music, and the Eternal Father of Italian music.” In James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses (1934), Joyce's friend Frank Budgen quotes him as saying "that in writing this Mass, Palestrina saved music for the church." Palestrina’s magisterial image was set in stone.

Chorale is finding the Pope Marcellus Mass to be a very rewarding project. The music is lovely, soothing, uplifting; it flows so naturally and effortlessly, one would imagine its composition to have been easy for the composer. The more deeply we delve into it, however, the more we discover Palestrina’s craft and skill, and the genius of his contrapuntal writing. I discover, myself, a similarity to Mozart’s music: a gracious, pleasing, untroubled surface, a kind of abstract perfection: but so difficult to describe and define, once one is inside it. It demands extraordinary skill and grace in performance; and yields, on its own, incredible richness and satisfaction. Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.

Adventures in Programming

Chorale’s current project features some of the most unusual programming we have ever put out there.

Chorale’s current project features some of the most unusual programming we have ever put out there. We have paired two major a cappella works which, on the surface, bear little resemblance to one another: the magisterial Missa Papae Marcelli by G.P. da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594), and The Peaceable Kingdom by Randall Thompson (1899-1984). The two works are approximately the same length, and require similar vocal forces; and they are both pieces with which most choral musicians are broadly familiar, but which few of them have actually sung. The Mass is cited in music history texts as the pinnacle of Palestrina’s writing, reflecting the compositional elements which influenced generations of church musicians which followed him; and Randall Thompson, the “dean of American composers,” has been afforded a similar status by twentieth century American musical critics. Both men, and their works, are revered, hoary monuments, referenced but somehow no longer current. Our goal, this spring, is to encounter them where the rubber hits the road, in performance, and rediscover what made them so important in the first place.

The League of Composers commissioned Thompson in 1935 to write a major work for unaccompanied chorus. He chose as his point of departure a primitivist painting entitled “The Peaceable Kingdom” by Edward Hicks (1780-1849), “the preaching Quaker of Pennsylvania.” It illustrates Isaiah XI:6-9:

The League of Composers commissioned Thompson in 1935 to write a major work for unaccompanied chorus. He chose as his point of departure a primitivist painting entitled “The Peaceable Kingdom” by Edward Hicks (1780-1849), “the preaching Quaker of Pennsylvania.” It illustrates Isaiah XI:6-9:

The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them. And the cow and the bear shall feed; their young ones shall lie down together: and the lion shall eat straw like the ox. And the suckling child shall play on the hole of the asp, and the weaned child shall put his hand on the cockatrice’ den. They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain: for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea.

In the middle distance, William Penn negotiates with the Indians by the shore of the Delaware River.

Inspired both by the painting and by the passage it illustrates, Thompson studied the book of Isaiah and selected eight passages referencing themes of peace and violence, and of good versus evil. In general, Thompson’s compositional style is conservative-- he prefers triadic harmonies, melodic sequences, imitative passages, Renaissance modality, and Venetian polychoral texture—but the stark contrasts in the Isaiah text inspire vivid, imaginative text-setting, appropriately dissonant harmonic passages, and large sections of recitative-like declamation, alternating with luscious, lyrical sections. He is able to express a variety of moods effectively, keeping interest and anticipation high. And the composer’s ordering of his text sets up a successfully dramatic narrative trajectory-- the work as a whole has a satisfying shape and arch, with a reassuring climax. I have, myself, had the opportunity to sing quite a lot of Thompson’s choral music over the years, and find this to be the most successful and satisfying of his major works—and also the freshest and most creative, considering the passage of years since he was actively composing. “Primitivism,” with Thompson as well as with Hicks, refers to conception, rather than execution; both men have the sophistication and skill to accomplish major works, but are freed from the rigidity of their respective disciplines by Isaiah’s prophetic vision and language. Chorale and I are finding this to be a fresh, intriguing piece to work on, quite different from anything else we have ever performed.

Meet Chorale's B Minor Soloists

Chicago Chorale has a roster of outstanding soloists for its upcoming performance of the Mass in B Minor, March 26.

Chicago Chorale has a roster of outstanding soloists for its upcoming performance of the Mass in B Minor, March 26:

Michigan native Chelsea Shephard, soprano, recently gave an “exquisite” NYC recital debut, garnering praise for her “beautiful, lyric instrument” and “flawless legato” (Opera News). This season includes Ms. Shephard’s Carnegie Hall debut with Cecilia Chorus of New York for a World Premiere by Syrian composer Zaid Jabri and Brahms Requiem, joining Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster for Das Rheingold, and return engagements with the Madison Bach Musicians. Past season highlights include: Beth/Little Women, Calisto/La Calisto, Pamina/Die Zauberflöte, Susanna/Le nozze di Figaro, Lauretta/Gianni Schicchi, Lisa/The Land of Smiles, Emily Webb/Our Town, and Poppea/L’incoronazione di Poppea with companies such as Madison Opera, Opera Grand Rapids, Haymarket Opera Company, and Caramoor International Music Festival. Ms. Shephard’s accolades include: Education Grant/Metropolitan Opera National Council (2016), Finalist/Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ryan Opera Center (2015), First Place/Madison Early Music Festival Handel Aria Competition (2014), and Finalist/Jensen Foundation Competition in NYC (2014).

Michigan native Chelsea Shephard, soprano, recently gave an “exquisite” NYC recital debut, garnering praise for her “beautiful, lyric instrument” and “flawless legato” (Opera News). This season includes Ms. Shephard’s Carnegie Hall debut with Cecilia Chorus of New York for a World Premiere by Syrian composer Zaid Jabri and Brahms Requiem, joining Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster for Das Rheingold, and return engagements with the Madison Bach Musicians. Past season highlights include: Beth/Little Women, Calisto/La Calisto, Pamina/Die Zauberflöte, Susanna/Le nozze di Figaro, Lauretta/Gianni Schicchi, Lisa/The Land of Smiles, Emily Webb/Our Town, and Poppea/L’incoronazione di Poppea with companies such as Madison Opera, Opera Grand Rapids, Haymarket Opera Company, and Caramoor International Music Festival. Ms. Shephard’s accolades include: Education Grant/Metropolitan Opera National Council (2016), Finalist/Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ryan Opera Center (2015), First Place/Madison Early Music Festival Handel Aria Competition (2014), and Finalist/Jensen Foundation Competition in NYC (2014).

Chelsea holds degrees from DePaul University and Rice University.

Mezzo-soprano Angela Young Smucker has earned praise for her “luscious” voice (Chicago Tribune) and "powerful stage presence" (The Plain Dealer). Her performances in concert, stage, and chamber works have made her a highly versatile and sought-after artist. Highlights of the 2016-17 season include performances with Haymarket Opera Company, Bach Collegium San Diego, Chicago A Cappella, Seraphic Fire, and newly-founded Third Coast Baroque. Ms. Smucker has also been a featured soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Music of the Baroque, Oregon Bach Festival, Bella Voce, and Les Délices. Radio and television appearances include Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, WFMT’s Impromptu and Live from WFMT, and WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Mezzo-soprano Angela Young Smucker has earned praise for her “luscious” voice (Chicago Tribune) and "powerful stage presence" (The Plain Dealer). Her performances in concert, stage, and chamber works have made her a highly versatile and sought-after artist. Highlights of the 2016-17 season include performances with Haymarket Opera Company, Bach Collegium San Diego, Chicago A Cappella, Seraphic Fire, and newly-founded Third Coast Baroque. Ms. Smucker has also been a featured soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Music of the Baroque, Oregon Bach Festival, Bella Voce, and Les Délices. Radio and television appearances include Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, WFMT’s Impromptu and Live from WFMT, and WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Currently pursuing her doctoral studies at Northwestern University, Ms. Smucker holds degrees from the University of Minnesota and Valparaiso University – where she also served as instructor of voice for seven years. She is a NATS Intern Program alumna, former Virginia Best Adams Fellow (Carmel Bach Festival), and serves as Executive Director of Third Coast Baroque.

A "superb vocal soloist" (The Washington Post) possessing a "sweetly soaring tenor" (The Dallas Morning News) of "impressive clarity and color" (The New York Times), tenor Steven Soph performs throughout North America and Europe. Recent seasons' highlights include appearances with The Cleveland Orchestra in an all-Handel program led by Ton Koopman; the New World Symphony and Seraphic Fire in Reich's Desert Music; Symphony Orchestra Augusta in Bach's B minor Mass; San Diego's Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra in Mozart's "Orphanage" Mass and Mass in C minor; Voices of Ascension in Bach's Magnificat and St. Matthew Passion; the Master Chorale of South Florida in Mozart's Requiem and Haydn's Lord Nelson Mass; Colorado Bach Ensemble in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion; Texas Choral Consort in Haydn's Creation; and the Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra in Handel's Messiah.

A "superb vocal soloist" (The Washington Post) possessing a "sweetly soaring tenor" (The Dallas Morning News) of "impressive clarity and color" (The New York Times), tenor Steven Soph performs throughout North America and Europe. Recent seasons' highlights include appearances with The Cleveland Orchestra in an all-Handel program led by Ton Koopman; the New World Symphony and Seraphic Fire in Reich's Desert Music; Symphony Orchestra Augusta in Bach's B minor Mass; San Diego's Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra in Mozart's "Orphanage" Mass and Mass in C minor; Voices of Ascension in Bach's Magnificat and St. Matthew Passion; the Master Chorale of South Florida in Mozart's Requiem and Haydn's Lord Nelson Mass; Colorado Bach Ensemble in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion; Texas Choral Consort in Haydn's Creation; and the Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra in Handel's Messiah.

Described as an Evangelist “first-class across the board,” (Chicago Classical Review) Steven performed with the Chicago Chorale in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion, at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion and with the Concord Chorale in the St. John Passion.

Steven holds degrees from the University of North Texas and Yale School of Music, where he studied with renowned tenor James Taylor.

Ryan de Ryke (baritone) is an artist whose versatility and unique musical presence have made him increasingly in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. He has performed at many of the leading international music festivals including the Aldeburgh and Edinburgh Festivals in the UK and the summer festival at Aix-en-Provence in France garnering significant acclaim as both a recitalist and singing actor.

Ryan de Ryke (baritone) is an artist whose versatility and unique musical presence have made him increasingly in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. He has performed at many of the leading international music festivals including the Aldeburgh and Edinburgh Festivals in the UK and the summer festival at Aix-en-Provence in France garnering significant acclaim as both a recitalist and singing actor.

Ryan studied at the Peabody Conservatory with John Shirley Quirk, the Royal Academy of Music in London with Ian Partridge, and at the National Conservatory of Luxembourg with Georges Backes. His is also an alumnus of the Britten-Pears Institute in the UK and the Schubert Institute in Austria where he worked with great artists of the song world such as Elly Ameling, Wolfgang Holzmair, Julius Drake, Rudolf Jansen, and Helmut Deutsch.

Ryan can often be seen collaborating with Haymarket Opera Chicago where he performed title role in Telemann’s Pimpinone, voted one of Chicago’s top 5 performances of 2013, and last season played the role of Sancho Panza in Don Quichotte.

My Third Time Around

How will I experience my fourth B Minor Mass performance? I don’t know, but I hope I’m lucky enough to find out.

Guest Blog by Dan Bertsche, who has sung tenor with Chicago Chorale since 2003, and currently serves as Secretary on Chicago Chorale’s Board of Directors.

Guest Blog by Dan Bertsche, who has sung tenor with Chicago Chorale since 2003, and currently serves as Secretary on Chicago Chorale’s Board of Directors.

I remember approaching my first Bach B Minor Mass, in 2006, something like Sir Edmund Hillary must have approached his ascent of Mount Everest. This work is so difficult and monumental, and the only path I saw to a successful performance was through hard work, by developing lung capacity, stamina, and endurance—and by staying hydrated. Rehearsals were exhilarating, but at the same time fatiguing. After that first performance, the profound satisfaction I felt was coupled with equally profound exhaustion—both physical and vocal. “I came, I sang, I conquered. Now I want to sleep.”

My second B Minor Mass—six years ago—felt quite different. My familiarity with the score, coupled with the fact that everything was pitched at a=415 (a half-step down), allowed more space for appreciating what makes this work so very great in the first place. This was no longer a forced march to the mountaintop; but a walk through a garden of wonders. I recall marveling at the complexity and perfection of the Kyrie I; admiring the skill with which the cantus firmus emerges from the secondary material in Confiteor (still my favorite movement of the entire work); and being astounded by how there could be so many 16th notes in so many voices and instruments in the Cum Sancto Spiritu, and that the movement could still come across with such clarity and coherence. During my second B Minor Mass, I learned to appreciate Bach as “master composer,” rather than as “master obstacle-course builder.”

This year, some of my reverence for Bach’s compositional skill has been replaced by more general gratitude for this monumental work. Had Bach not bothered to compose it, or had it been lost to history, right now Chicago Chorale would frankly be preparing to perform a lesser piece. But because of this gift to posterity, fifty-five ordinary people are experiencing the magic that happens when engaging this extraordinary work. And as we strive to bring out the very best in the B Minor Mass, the B Minor Mass is bringing out the very best in us. Our collective vocal production is more healthy and vigorous; we are listening better within and across sections; we are sitting up a bit straighter; and we are more honest with ourselves about which spots need individual attention. On some level, Chorale members know that a great performance of a mediocre work still yields a mediocre result. So we are grateful that Bach has given us a masterpiece with a nearly unlimited performance “upside potential,” and we are pulling together to get as close to that ceiling as possible.

This time around, I am also struck by how much fun rehearsals are, by how much I look forward to them, and by the fact that I leave each rehearsal more energized than when I arrive.

How will I experience my fourth B Minor Mass performance? I don’t know, but I hope I’m lucky enough to find out.

Chorale's Choices

No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

I have written largely about the historical/musicological aspects of presenting Bach’s Mass in B Minor, over the past weeks. Such a focus is inevitable: the score is enormous, complex, surrounded and influenced by competing traditions; a conductor is forced to make decisions about every page, and to coordinate these many decisions in order to come up with a coherent whole. No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

In the performance history of the work, enormous choruses, numbering in the hundreds, have sung, and continue to sing, the Mass in B Minor, though the general trend has been toward smaller forces– on occasion, just one singer per part. Chorale is fifty-six singers for this concert-- by no means a symphony chorus, but larger than the professional early music ensembles which present the most cutting edge versions of the work. We could have chosen to bypass the work altogether, in acknowledgment of historical correctness– but then we would be deprived of the glorious experience of learning and performing the work, and our audience would be deprived of the opportunity to hear it. So we choose to sing it, and to devote tremendous effort toward lightening our sound and articulation, while making the most of our full sound where it is needed and welcome.

I have written largely about the historical/musicological aspects of presenting Bach’s Mass in B Minor, over the past weeks. Such a focus is inevitable: the score is enormous, complex, surrounded and influenced by competing traditions; a conductor is forced to make decisions about every page, and to coordinate these many decisions in order to come up with a coherent whole. No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

In the performance history of the work, enormous choruses, numbering in the hundreds, have sung, and continue to sing, the Mass in B Minor, though the general trend has been toward smaller forces– on occasion, just one singer per part. Chorale is fifty-six singers for this concert-- by no means a symphony chorus, but larger than the professional early music ensembles which present the most cutting edge versions of the work. We could have chosen to bypass the work altogether, in acknowledgment of historical correctness– but then we would be deprived of the glorious experience of learning and performing the work, and our audience would be deprived of the opportunity to hear it. So we choose to sing it, and to devote tremendous effort toward lightening our sound and articulation, while making the most of our full sound where it is needed and welcome.

Frequently, even when larger groups sing it, a smaller group, termed concertists, will introduce many of the movements, will sing particularly exposed passages as solos, will even sing the more intimate movements entirely on their own. Sometimes, these concertists will be members of the choir; alternatively, they may be the soloists who also sing the aria and duet movements. This trend toward ripienist/concertist texture is supported by the scholarly literature. Chorale chooses to forego the ripienist/concertist procedure. It could have been interesting and appropriate for our forces, but our singers want to experience all of the music, each note, as an amateur event—an act of love. As Robert Shaw said—music, like sex, is too good to be left to the professionals. Again, this forces us to be more careful in our control of texture and dynamics than we would be if those issues were resolved through controlling the size of the forces.

Chorale chooses to sing the Latin text with a German pronunciation. Most ensembles use the more common Italianate pronunciation, and have good results; and recent research indicates that the German pronunciation Chorale uses, based on modern German, is not necessarily the pronunciation Bach used or intended. So we can’t defend our choice on a secure, scholarly basis. But our choice does suggest the music’s German background. And I agree with Helmuth Rilling’s contention that German consonants articulate more clearly than Italian, while German vowels narrow and clarify the vocal line, even for an entire section of singers, lending greater definition to Bach’s remarkably complex counterpoint. This is particularly necessary with a group of our size: clarity of pitch and line is far more important, in this music, than the beautiful, Italianate production of individual voices in the ensemble, which can actually work against an accurate presentation of Bach’s musical ideas.

We choose to present the Mass at Rockefeller Chapel, on the campus of The University of Chicago, because the building’s size and grandeur reflect Bach’s music more accurately than other spaces available to us. The Hyde Park community, which surrounds the Chapel, represents, in a purer form than other Chicago neighborhoods, the combination of scholarship, idealism, and high culture which can support concerts like this. A high percentage of Chorale’s regular audience are Hyde Park residents, and they often express appreciation for the level of Chorale’s striving and seriousness of intent. And from a purely monetary point of view, Rockefeller Chapel seats a sufficient number of listeners that, if we sell tickets effectively, we can cover a significant proportion of our production costs (which are mind-boggling) with door receipts.

We choose to present the Mass at Rockefeller Chapel, on the campus of The University of Chicago, because the building’s size and grandeur reflect Bach’s music more accurately than other spaces available to us. The Hyde Park community, which surrounds the Chapel, represents, in a purer form than other Chicago neighborhoods, the combination of scholarship, idealism, and high culture which can support concerts like this. A high percentage of Chorale’s regular audience are Hyde Park residents, and they often express appreciation for the level of Chorale’s striving and seriousness of intent. And from a purely monetary point of view, Rockefeller Chapel seats a sufficient number of listeners that, if we sell tickets effectively, we can cover a significant proportion of our production costs (which are mind-boggling) with door receipts.

Our concert is in one month. Sunday, March 26, 3 p.m.

We have rehearsed, and I have written about the experience, since the middle of December. The writing has focused my study, my listening, my thinking about the work; it has been a significant and helpful discipline for me. I hope you will come to our performance; and I hope you will spread the word, and bring your friends. I’m a believer; I am convinced that Bach’s Mass in B minor truly is “the greatest artwork of all times and all people,” and I’d like to show you why.

Composing the Mass in B Minor

Bach effectively spent his entire career composing Mass in B Minor— it consists of complete movements, and fragments, from throughout his compositional life, recomposed, reworded, reconfigured, stitched together with newly composed music.

Bach effectively spent his entire career composing Mass in B Minor— it consists of complete movements, and fragments, from throughout his compositional life, recomposed, reworded, reconfigured, stitched together with newly composed music — Bach scholar Christoph Wolff calls the Mass a “specimen book,” a collection of examples of genres and techniques which covers not only Bach’s personal history, but the history of Western music. In the process of compiling this music into a single great work, at the end of his life, Bach seems intent on summing up that history and presenting his summation to his successors. The Sanctus was first performed in 1724; movement 4 of the Credo, Et incarnatus est, thought to be the last music he composed, dictated to an assistant because Bach himself was blind, was completed in 1750. The remaining music reflects Bach’s experience during the intervening 26 years. Plagiarism and parody were not a dirty words in Bach’s time. Bach, and his colleagues, had immense responsibilities in the preparation and performance of music for the theater, the court, the church– and their success depended on getting it all done, rather than on satisfying a theoretical mandate that they be original. They were free, even expected, to build upon the successes of others, to copy and share one another’s scores, to use procedures and formulas, melodies and bass lines, that had worked well for other composers, and alter them to suit their own tastes and circumstances, even to change their own products and procedures over time as needs and tastes changed. Music was a living, volatile consumer product, constantly evolving to meet demand. Creativity reflected one’s ability to arrange the materials at hand, as well as to invent new materials. Bach borrowed freely and happily from other composers, as well as from himself, both because this enriched his product, and because it allowed him to keep up with his workload. It is inconceivable that Bach could have accomplished all he did in his lifetime, were he under pressure to stay away from the intellectual property of others.

An extraordinary amount of Bach scholarship over the past century has focused on sleuthing out the sources behind Bach’s music, and in preparing new and better editions of his music, based on this detective work. And while the scholars involved in this work frequently disagree with one another, as a group they persistently push the envelope, and contribute to our knowledge of the composer and his methods. Between them, these researchers have determined that very little of what is now called Mass in B Minor was freshly composed for the work– perhaps as few as four or five movements. Bach selected music for the remaining movements from cantatas which he had composed throughout his career. Scholars agree that he seems to have chosen what he thought was his best work, music which would suit the character of the Mass, and would reflect accurately the new, Latin texts. He transposed some movements to new keys, in keeping with the overall key structure of the new work; he adapted phrase structure to fit the alternate texts; he eliminated instrumental introductions and interludes, to move the dramatic action forward more efficiently; and he composed new movements, and sections of movements, where he needed them to complete the work.

Though the Ordinary of the Roman Catholic Mass consists of only five movements—Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus/Benedictus/Osanna, and Agnus Dei—Bach divides the text and music of his Mass in B Minor into twenty-three separate movements. With the exception of the Gratias/Dona nobis movements, and the repeat of the Osanna, each movement has different music.

Let’s consider movements 3-6 of the Credo portion: Et in unum Dominum, Et incarnatus est, Crucifixus, and Et resurrexit. Scholars agree, based on internal evidence, that Bach adapted the duet Et in unum from an earlier composition, though that earlier work is lost. The close imitation between the two voices is ideally suited to a love duet, probably from a secular work, and adapts easily to a text which expresses the consubstantiality of the Father and the Son. In his original version of the Mass, Bach set the entire text of movements three and four within this one movement. It was only in the final months of his life (determined, again, on the basis of internal evidence) that he decided he needed a separate movement to set the words “And was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man.” So he kept the music for movement 3 intact, had the soloists repeat earlier words, and composed a completely new movement — one of the few freshly-composed movements in the Mass, and one of Bach’s final compositional efforts. In so doing, he created a numerical symmetry which the Credo had previously lacked, placing the Crucifixus exactly at the center of this discrete section, as well as at the center of all of the Mass movements which lie between the identical music of the Gratias and the Dona nobis movements. It is an amazing engineering feat, adding internal structure for the connoisseur and first time listener alike.

Bach adapted the Crucifixus movement from his cantata BWV 12, where it has the words Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, lamentation,worry, apprehension). Bach scholar John Butt hypothesizes that Bach could have adapted even this early cantata movement (1714) from a similar movement by Vivaldi (Piango, gemo, sospiro e peno), but goes on to say that such laments were standard literary forms, and that, together with its descending bass line, is such a standard form that it would be stretching things to suggest that Bach did anything other than compose his own version of a common form. More interesting are the final four bars of the Crucifixus; Bach added these to the music he borrowed from himself, and with them modulates to G Major (setting up the D Major of the following Et resurrexit) and brings the choral forces down to the lowest pitches they sing in the entire Mass, representing the lowering of Christ’s body into the sepulchre. The following movement, Et resurrexit, explodes out of this depth with no instrumental introduction—voices and instruments enter with a complete change of affect, in a fanfare-like, rising triad. Scholars assume that this movement, as well, is adapted from an earlier, secular cantata—possibly the lost birthday cantata for August I, BWV Anh. 9. In adapting it, Bach dropped the opening instrumental introduction, which would have slowed down the drama of Easter morning, but included other instrumental interludes, which have a euphoric, dance-like character and seem to suggest heaven and earth rejoicing.

Bach adapted the Crucifixus movement from his cantata BWV 12, where it has the words Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, lamentation,worry, apprehension). Bach scholar John Butt hypothesizes that Bach could have adapted even this early cantata movement (1714) from a similar movement by Vivaldi (Piango, gemo, sospiro e peno), but goes on to say that such laments were standard literary forms, and that, together with its descending bass line, is such a standard form that it would be stretching things to suggest that Bach did anything other than compose his own version of a common form. More interesting are the final four bars of the Crucifixus; Bach added these to the music he borrowed from himself, and with them modulates to G Major (setting up the D Major of the following Et resurrexit) and brings the choral forces down to the lowest pitches they sing in the entire Mass, representing the lowering of Christ’s body into the sepulchre. The following movement, Et resurrexit, explodes out of this depth with no instrumental introduction—voices and instruments enter with a complete change of affect, in a fanfare-like, rising triad. Scholars assume that this movement, as well, is adapted from an earlier, secular cantata—possibly the lost birthday cantata for August I, BWV Anh. 9. In adapting it, Bach dropped the opening instrumental introduction, which would have slowed down the drama of Easter morning, but included other instrumental interludes, which have a euphoric, dance-like character and seem to suggest heaven and earth rejoicing.

In his handbook for the study of the Mass in B Minor, John Butt recounts the experience of early Bach scholar Julius Rietz, who wrote the first published study of the sources of the Mass in 1857: “Reitz shows himself to have been a meticulous scholar, who even made enquiries into the fate of Bach’s first set of parts of the Sanctus, copied in 1724 and loaned to Graf Sporck. The inheritors of the estate informed Rietz that many manuscripts had been given to the gardeners to wrap around trees. One can barely dare to envisage what similar fates befell other manuscripts from Bach’s circle.” I expect Bach would not have been surprised by this; the archives and libraries of our modern world would probably astound him. Christoff Wolff suggests that one of the principle motivations behind Bach’s compilation of the Mass was his assumption that the thousands of pages of his cantata cycles would not be preserved—that they were too specific to their own time, location, and purpose to be of any use once he was gone, and that the only way he could preserve the best of his work was to use it for a Latin Mass, which would have a better chance of being saved and recognized in the future. My years of participation in the Oregon Bach Festival have given me the opportunity to sing and study many of Bach’s surviving cantatas, but I am lucky to have had this experience—most performers know only a handful of them, and most listeners don’t know them at all. So from our viewpoint, Bach had it right—his Mass enables us to know not only what he was able to preserve, but also the dimensions of our loss.

I read somewhere that Bach shows us what it means to be God, Mozart shows us what it means to be human, and Beethoven shows us what it means to be Beethoven. I agree with the Bach part, at least. Beyond the notes, the rhythms, the historically informed performance practices, one experiences his works as living beings, as manifestations of God in the world. They demonstrate that we humans are better than we think we are, better than much of what we see around us, and convince me that it is always worth it to keep moving ahead, not just out of habit, but because we, like Bach, are capable of holy things.

Chicago Chorale and Historically Informed Performance Practice

Bach was not only a genius; he was a practical, practicing musician. Knowing what he heard, and how he did it, can only improve our performances of his work.

I began attending Oberlin Conservatory’s Baroque Performance Institute in 1978, and continued attending for about eight summer sessions following that. I first learned of the Institute through Ken Slowik, a Chicago cellist and early music specialist, who suggested that my vocal characteristics and musicological curiosity might make me a good candidate for BPI-- especially since Baroque expert Max Van Egmond was joining the faculty that summer. I listened to some of Max’s recordings, recognized a kindred spirit, and decided to take the plunge. The experience was revelatory for me: prior to that, I had never even heard of Baroque pitch, of gut strings, of wooden traverso flutes, of viols, of inégale rhythm. An entirely new world opened for my consideration, and I ate it up, eagerly and hungrily. Max was an ideal teacher and mentor for me, and I sang as often as I could, in lessons, master cases, and concerts; and I observed instrumentalists when I was not singing. BPI was all about performance; scholars and theorists attended, lectured, and added their insights, but the focus was on performing, day and night. I had never loved any musical immersion so much, in my life.

And then, when BPI was over, I would return to my job, conducting choirs and teaching voice, first at Luther College, later at The University of Chicago—and I would have a hard time integrating my BPI experience with my actual day job. One year Ken invited me to sing with the Smithsonian Chamber Players (he was by this time their music director) in Washington, for a performance of Charpentier’s Les Arts Florissants , complete with dance, masks, authentic instruments from the Smithsonian collection—we were so authentic, we even lighted the performance with candles in metal reflectors. The other singers were recognized professionals in the early music field, who did this sort of thing on a regular basis; for me, it was a brief interlude, a vacation, from my teaching. The contrast struck me forcibly, and I withdrew from involvement in early music performance from that point on—I could not see any further value in doing it part way, and I did not want to give up my actual professional life. I enjoyed my students, my choirs, and could not see how this hobby of mine was contributing anything to the health of my program.

I began attending Oberlin Conservatory’s Baroque Performance Institute in 1978, and continued attending for about eight summer sessions following that. I first learned of the Institute through Ken Slowik, a Chicago cellist and early music specialist, who suggested that my vocal characteristics and musicological curiosity might make me a good candidate for BPI-- especially since Baroque expert Max Van Egmond was joining the faculty that summer. I listened to some of Max’s recordings, recognized a kindred spirit, and decided to take the plunge. The experience was revelatory for me: prior to that, I had never even heard of Baroque pitch, of gut strings, of wooden traverso flutes, of viols, of inégale rhythm. An entirely new world opened for my consideration, and I ate it up, eagerly and hungrily. Max was an ideal teacher and mentor for me, and I sang as often as I could, in lessons, master cases, and concerts; and I observed instrumentalists when I was not singing. BPI was all about performance; scholars and theorists attended, lectured, and added their insights, but the focus was on performing, day and night. I had never loved any musical immersion so much, in my life.

And then, when BPI was over, I would return to my job, conducting choirs and teaching voice, first at Luther College, later at The University of Chicago—and I would have a hard time integrating my BPI experience with my actual day job. One year Ken invited me to sing with the Smithsonian Chamber Players (he was by this time their music director) in Washington, for a performance of Charpentier’s Les Arts Florissants , complete with dance, masks, authentic instruments from the Smithsonian collection—we were so authentic, we even lighted the performance with candles in metal reflectors. The other singers were recognized professionals in the early music field, who did this sort of thing on a regular basis; for me, it was a brief interlude, a vacation, from my teaching. The contrast struck me forcibly, and I withdrew from involvement in early music performance from that point on—I could not see any further value in doing it part way, and I did not want to give up my actual professional life. I enjoyed my students, my choirs, and could not see how this hobby of mine was contributing anything to the health of my program.

My succeeding summers were spent, first, at the Nice Conservatory, singing art songs with Gérard Souzay and Dalton Baldwin; then several years with the Robert Shaw Festival Singers; and, finally, ten summers with Helmuth Rilling at the Oregon Bach Festival. All of it was good and worthwhile and stimulating, and contributed to my professional competence.

What goes around, comes around. The bug that bit me back at Oberlin did not die; it just invaded the rest of my music making. Working with both Mr. Shaw and Mr. Rilling, I found myself observing and questioning what they were doing, comparing it to my BPI experience, wondering how it was related, how it could be different, and how I could do things differently, myself, with my own ensembles. During Chorale’s second season, already, we presented the first half of J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, and we have been programming major Baroque works, primarily Bach’s, ever since. With each successive concert, I introduce more HIPP elements, try more techniques I remember from my Oberlin experiences, require a more “baroque” sound from both the players and the singers, hire more appropriate soloists. Obviously, we do not do museum-quality reproductions of performances that Bach himself led or heard: we do not have his performance space, his highly trained 16-year old prepubescent boys, or his audience. We prepare performances for the buildings we have, with the singers we have, and with our contemporary audiences in mind. But, as I discovered at Oberlin, having a good idea of Bach’s circumstances, knowing what was physically and musically possible for him, and being aware of his goals—his desire to clarify, to instruct, to be understood, to get his message across—has really helped me to sort out what is good and necessary in what I learned at BPI. Bach was not only a genius; he was a practical, practicing musician. Knowing what he heard, and how he did it, can only improve our performances of his work.

Why Did Bach Compose the Mass in B Minor

Not until I moved to Chicago for graduate school did I begin to understand that the Lutheranism I knew bore only a faint resemblance to that practiced in Bach’s time.

I grew up in a fairly segregated atmosphere: most Roman Catholics lived on the east side of town and attended Catholic school, while the rest of us, primarily Lutherans, lived on the west side and attended public school. The two groups were not, strictly speaking, enemies, but our friends were within our own group, we participated in our own communal activities, and we did not have much to do with one another. I never set foot in the Catholic church; we stayed clear of masses, along with priests and nuns and the Virgin Mary. I assumed no kinship between what Lutherans did on Sunday, and what the Catholics did. My public school music teachers were Lutheran, and my piano teacher was a Lutheran; in my mind, music was a Lutheran thing. The Lutheran hymnal had hymns by J.S. Bach—he was “ours,” and we claimed him, though we knew little about him. I had no idea at all that Bach had composed several settings of the mass, and that these settings were in Latin, the same language used at our town’s Catholic church. I attended a Lutheran college, where courses in religion and music history taught me something about Roman Catholicism and broadened my knowledge of the mass as a liturgical structure and as the basis for extended musical form; but my viewpoint remained pretty parochial. Not until I moved to Chicago for graduate school did I begin to understand that the Lutheranism I knew bore only a faint resemblance to that practiced in Bach’s time. Lutherans continue to claim Bach—some refer to him as the “fifth evangelist,” while others stress a symbolic father-son relationship between him and Martin Luther: Luther clarified the faith, and Bach set it to music. Some writers even describe a “Lutheran” approach to the interpretation and performance of Bach’s music.

By all accounts, Bach was deeply religious. Although his professional responsibilities throughout his life included obligations to secular as well as religious authorities, and his surviving compositions reflect this career duality, the evidence revealed in his letters, in his professional trajectory, and in the very nature of his activities in liturgical composition and performance, leave little reason to doubt his fundamental piety and spirituality. There is little doubt, as well, that he was thoroughly Lutheran in his theology. But Lutheranism as Bach experienced it was more than theology—it was the state church, a source of power and preferment, and it shared a good deal of space with secular authority. When Bach compiled the first half of his mass—called the Missa, it consisted of the Kyrie and Gloria sections of the Ordinary— he was not only working comfortably within the traditions of the Lutheran Church (which continued, post-Reformation, to refer to the Eucharist as the “mass”), he was also seeking advancement from the court at Dresden, to whom he presented his Missa as a gift, in 1733. This limited (but complete) work, approximately one-half as long as the completed Mass in B Minor, did indeed receive a liturgical performance by the Dresden kapelle, and ultimately won for Bach the worldly preferment and protection he was seeking.

By all accounts, Bach was deeply religious. Although his professional responsibilities throughout his life included obligations to secular as well as religious authorities, and his surviving compositions reflect this career duality, the evidence revealed in his letters, in his professional trajectory, and in the very nature of his activities in liturgical composition and performance, leave little reason to doubt his fundamental piety and spirituality. There is little doubt, as well, that he was thoroughly Lutheran in his theology. But Lutheranism as Bach experienced it was more than theology—it was the state church, a source of power and preferment, and it shared a good deal of space with secular authority. When Bach compiled the first half of his mass—called the Missa, it consisted of the Kyrie and Gloria sections of the Ordinary— he was not only working comfortably within the traditions of the Lutheran Church (which continued, post-Reformation, to refer to the Eucharist as the “mass”), he was also seeking advancement from the court at Dresden, to whom he presented his Missa as a gift, in 1733. This limited (but complete) work, approximately one-half as long as the completed Mass in B Minor, did indeed receive a liturgical performance by the Dresden kapelle, and ultimately won for Bach the worldly preferment and protection he was seeking.

The larger question about Bach’s purpose is reflected in his “completion” of the Mass in the last years of his life. He in some respects pulled back from the day to day responsibilities of his position in Leipzig, and put his energy into the completion of major, somewhat theoretical works: Musical Offering, The Art of Fugue, and Mass in B Minor. In these works, he seems intent not only on establishing his own legacy, but in creating a veritable encyclopedia of western European musical styles, forms, and procedures.

It seems clear that Bach never intended his Mass for liturgical use—clocking in at two hours without a break, it is simply too long. Rather, it appears to be what Bach scholar Christoff Wolff calls the summa summarum of Bach’s artistry. Wolff goes on to say, “We know of no occasion for which Bach could have written the B-minor Mass, nor any patron who might have commissioned it, nor any performance of the complete work before 1750. Thus, Bach’s last choral composition is in many respects the vocal counterpart to The Art of Fugue, the other side of the composer’s musical legacy. Like no other work of Bach’s, the B-minor Mass represents a summary of his writing for voice, not only in its variety of styles, compositional devices, and range of sonorities, but also in its high level of technical polish. “

Performances of the work reflect not only our perceptions of Bach’s beliefs and intentions, but our personal entry to the work. The first complete productions of the Mass, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, stressed its magisterial qualities—depicting Bach as an extraordinary man who communed with God on a level beyond human emotion and expression. Near-universal acceptance and practice of the Christian faith, which influenced all thought and politics of Bach’s time, still held a great deal of sway 100 years later. Bach was seen as an almost sacred prototype for the heroic figure later realized in Beethoven— the first complete performance of the Mass, in 1859, was actually inspired by the success of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. Many modern performances stress, instead, Bach’s humanity, his imperfection, his kinship with musical tastes and procedures of his own time. This latter approach has invited participation by musicians who do not profess any religious creed, yet find the work to be universally compelling and uplifting. I suspect the Mass may be the most comprehensive, unifying work by any composer— Bach’s attempt to depict the universality behind both his private spirituality and the religious expression of his time. Albert Schweitzer described the work as one in which the sublime and intimate co-exist side by side, as do the Catholic and Protestant elements, all being as enigmatic and unfathomable as the religious consciousness of the work’s creator.

Black with Notes

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move.

Chorale is seven rehearsals into its preparation for our March 26 performance of Bach’s Mass in B Minor. I am grateful for so extended a rehearsal period-- every singer in the group benefits from repeated exposure to this complex, difficult music.

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move, aiming for the next harmonic arrival point, then taking off again once it is reached. The overall effect is—page after page of notes, thousands of them; how does one organize them? Where does one begin in breaking them down into comprehensible groupings, in assigning emphasis, ebb and flow, in such a way that they all make sense, all get heard, all matter and contribute positively, without just canceling one another out in a cloud of sound?

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move, aiming for the next harmonic arrival point, then taking off again once it is reached. The overall effect is—page after page of notes, thousands of them; how does one organize them? Where does one begin in breaking them down into comprehensible groupings, in assigning emphasis, ebb and flow, in such a way that they all make sense, all get heard, all matter and contribute positively, without just canceling one another out in a cloud of sound?

The first movement of the Mass in B Minor, Kyrie I, immediately plunges us into this “Bach problem.” After a 4-bar, homophonic introduction, the movement unfolds in thirteen independent musical lines, in addition to the continuo line. Singers aren’t accustomed to thinking much about instrumental lines– we see five vocal lines, and figure our job is to make sense of those; it surprises us to learn that the instruments do more than just accompany us, and have their own, independent lines, weaving in and out of what we are doing. Fundamentally, there is no hierarchy; each line contributes equally to Bach’s structure and texture. We need to find hierarchy within our own lines—periods of higher energy, balanced with periods of relaxation; figures which require pointed, staccato or marcato emphasis, and figures with require legato; passages of a more soloistic character, and passages of background accompaniment. If we don’t find hierarchy within our own parts, relative to the rest of what is going on, we end up sound like a beehive on a warm day, lots and lots of buzzing.

A Chorale member commented on a performance of the Mass with his college choir, that “we just tried to sing the notes; we never did anything with all this articulation stuff.” I know what he is talking about: even with a high percentage of singers who have previously performed the work, Chorale struggles to find pitches and rhythms; vocal quality, articulation, phrasing, would be complete non-starters, were I not constantly stopping to point them out, dictate them, and work on them. The Bärenreiter piano-vocal scores we sing from are “clean”—they include very little that Bach himself did not notate in his own scores, and Bach did not customarily notate much in the vocal lines. The instrumental lines are fairly marked up, following Bach’s own score and parts, and many of these marks have been transferred to the piano reduction in the singers’ scores—but singers are not prone to look down to the piano line: following their own line is about all they accomplish at this point. So we transfer the markings to the vocal parts in rehearsal, and then rehearse characteristic phrase articulations, ornaments, etc. Taken by themselves, these articulations can seem pretty mechanical and not awfully graceful; they have to be performed with understanding and within the context of the vocal line, and this is extremely difficult– Bach demands a great deal. I urge the singers to listen to the 2015 Gardiner recording, as an example of the sort of articulation and expressiveness we are after; but it takes a great deal of familiarity for them to internalize these gestures and allow them to mean something, rather than just perform them mechanically. The individual lines have to flow; they have to alter in emphasis and adjust to the volume, the surrounding parts, the intensity of individual passages; and this requires far more than mechanical competence and repetition.