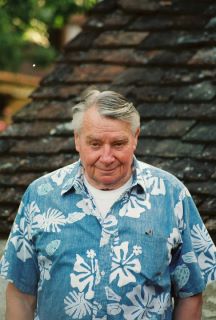

Robert Shaw's Advice for Conductors

Something I recently found posted on Facebook:

Something I recently found posted on Facebook:

Good Advices for All Conductors (by Robert L. Shaw)

1. Love your singers.

2. Love humanity.

3. Insist on personal and musical integrity.

4. Study your music until you know it as well as the composer.

5. Study your music again and again until you know it as well as the composer.

6. Strive to perfect the technique of music so that the heart of the music may shine through.

7. Love your family.

8. Spend time with your family.

9. Maintain your sense of humor

In its original form, this list is presented in faux-gothic script, centered on the page—like Charlton Heston’s ten commandments. Mr. Shaw always maintained his sense of humor. I would like to add a couple more, from my own experience (it's my blog, after all):

10. Pay attention to what your colleagues are doing.

11. Keep up your instrument.

12. Get outside.

Now for Lutheran catechetical exegesis:

1. & 2. These can be pretty tough. He also said (though apparently did not commit to print) that a nice person could never be a good choral conductor. Mr. Shaw could be pretty rough on his singers, and so can the rest of us. On the one hand—where would we be, without them? They are our voice, and the voice of that humanity he advises us to love. Their physical, intellectual, and emotional gifts transform dots, lines, and circles into Bach and Beethoven. They show up rehearsal after rehearsal, put up with our inadequacies, sing their hearts out, and thank us when it is all over. They also will take advantage of any nuanced understanding we demonstrate regarding their personal situations, and push us to the edge regarding their special needs and desires. They will expect to be favored, complain that they are ill-treated and misunderstood, and be unable to sing week after week because of a cold. But Mr. Shaw is right—if our honest, heartfelt love for them does not triumph, if we cannot keep our appreciation, admiration, and gratitude ever before us, but instead let frustration, fatigue, and impatience get the better of us, if we cannot rescue our hearts from the abyss of disappointment, we will lose them — and then it is time to look for a new profession. Easier I think to “love humanity”—I am an Aquarius, and we are pretty happy to contemplate the glory of the human race and its endeavors; we are not so good with the nitty gritty. Mr. Shaw’s number one really speaks to me.

3. I’m not quite sure if we are to insist on our OWN integrity here, or on that of our singers. Mr. Shaw was a competitive, ambitious man—I can imagine him advising himself to behave. But I do know that he demanded the same of his singers-- if we were caught “cheating” in some sense, we lost his respect—even if that cheating was an expression of fearfulness or inadequacy. He was hard on us, and he was hard on himself. One thing I am sure of—a conductor must never demand of his singers, what he does not demand of himself.

4. & 5. There is no quicker way to derail a rehearsal, than to show up unprepared. It is not OK to think, Oh well, the singers are just starting to learn this, the concert is weeks away, I have time. If one insists on programming first-rate repertoire, one had better work hard to learn it—and work hard at ones presentation of it. Mr. Shaw was not a facile musician—he did not have a lot of formal training, and he had to work very, very hard to learn scores. And he always did. His score preparation and musical discipline were incredible examples of how to do things right.

6. Musicians like to ”feel” things-- technical work and preparation can feel tedious, contrived, lacking in spontaneity; it can seem to destroy the soul of the music, whatever that may be. Or so I thought back when I was eighteen and beginning my serious study of music. I have had wonderful teachers; I have had the undeserved good fortune to recognize and stay away from charlatans. All those wonderful teachers stressed, ad infinitum, the need for objectivity, clarity, patience, repetition, and open-eyed self-criticism in learning this craft. They rarely talked about talent; they talked about putting one note in front of the other. I have sung under many, many conductors who did not really understand the nuts and bolts of their craft, did not know how to solve problems—so when I began singing with Mr. Shaw, I wanted to jump for joy, both because of his demands, and because he knew how to help us meet those demands. He did not always have a clear sense of style or period, and occasionally he drilled awkwardness into us, rather than out of us; but his principles were always sound.

7. & 8. I think Mr. Shaw learned the value of family the hard way. But he learned it, and it sustained him powerfully, to the close of his remarkably long career. Plenty of conductors do not have families, in the conventional understanding of the term, and this may be prudent, given the requirements of career. I think one must broaden the understanding of family implied here—family can take many forms. Whatever that form, it should be expressive of such elements as mutual loyalty, dependability, longevity, support, nurturing-- ones craft and art are not diminished, sucked dry, by this interconnectedness and dependency, but rather fed and nourished by them.

9. I remember Mr. Shaw running really intense, demanding rehearsals, chewing us out, yelling at individuals, accusing us, the whole gamut of questionable personal behaviors of which he has accurately been accused-- and then he would tell a joke or a story, and the whole atmosphere would change, lighten up, and he had us again. Our acceptance and forgiveness of his harshness and his demands were essential to our relationship with him — we knew he was as flawed as we were, we saw ourselves in him; and his often corny, self-deprecating humor and quick wit felt like a sharing of himself. He knew he was nuts; we were glad he knew it, and quick to defend him. l have experienced other, humorless, unforgiving conductors who asked somewhat less than Mr. Shaw, yet really angered me because of the wall they maintained between themselves and their groups. They probably did not intend to do this, but didn’t trust us sufficiently to be one with us when we needed it. When I find myself erecting this same wall, I understand them better—but wish I didn’t do it, wish I had a lighter soul.

10. I think it is very important to attend concerts, even rehearsals, of my colleagues, listen to their CDs, look at their programs, check out their websites. Good bad or indifferent, they all have something, and know something, of which I am unaware; they all have something to teach me. I am very happy to steal from them, and happy to give them credit.

11. We have all these singers at our disposal; we (and the composers) ask a great deal of them. We are critical and accusing when they cannot produce, and impatient when they don’t respond as we expect them to. If we keep continue singing or playing, ourselves, we will not so easily lose sight of the issues which they confront while they work for us, and we will have firsthand information about how they can more closely satisfy our requirements. I think it especially important that we get on the other side of the podium every once in a while—even regularly, if time and energy permit; remind ourselves of what it feels like to be conducted, to be criticized, to be trying to adjust to those around us while reading new music. Singers—instrumentalists, too, I am sure—confront so many problems, so many variables, in practicing their craft; a good choral singer multitasks on the highest level, and part of his task is trying to follow and get along with us, who conduct them. It is good as well to experience for ourselves the visceral and spiritual joy of singing — good to remember why our singers want to be present.

12. The world has changed drastically in the past 100 years. Our crowding, our technology, our speed of travel, our mobility—these things have completely changed the way people live. We know that Beethoven and Brahms loved their walks in the woods, their long summer vacations in rural retreats; I think we can assume that their experience was not that hard to come by. What we don’t seem to realize is that their art was largely shaped by their perception of the natural world around them, a world they could hardly escape, even of they wanted to. Today, we can escape it very easily — and most of us do. We live at some distance from it, and perceive it second-hand. I find that I am most enthused/inspired/enthralled, as well as most clear-headed, when I take the time for daily walks along the lake, through the parks, watching the birds, the clouds, focusing my eyes on the distance this affords me. I have no doubt that it is this love of nature, which, more than anything else, transforms the notes I read in the score, into the shapes and emotions I find and express in musical performance. It is good for my health, and it makes me a better musician and communicator. Many of my colleagues say the same thing about their own experience. But one must make a conscious effort to set aside time and organize ones life in order to enable this.

What IS a “missa solemnis”? And why did Beethoven compose one?

This is Chorale’s year for “solemn masses”-- we will present two of them: Beethoven’s in March, Vierne’s in May.

This is Chorale’s year for “solemn masses”-- we will present two of them: Beethoven’s in March, Vierne’s in May. Probably a good idea to try and clear the air on terminology before talking more specifically about these works.

The basic text and function of the Roman Catholic mass originated in the very early church. This early development included the division of the text into an unvarying portion, called the “Ordinary,” and a portion appropriate to given days and festivals in the cyclical church year, called the “Propers.” Originally chanted in unison (think Gregorian chant), the presentation of the mass text became increasingly elaborate; by the late Medieval period, and forward through the Renaissance, it had developed into the single most important musical form available to composers, inspiring their imagination, ingenuity, and creativity.

Most Mass settings include only the five parts which constitute the Ordinary—Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Santus/Benedictus, and Agnus Dei-- which are fixed, presenting the same texts each time mass is celebrated. The term Missa Solemnis refers, technically, to a musical setting of all parts of the mass (except the readings)—the Ordinary and the Propers. Because the Propers are specific to each day in the liturgical calendar, a true Missa Solemnis could be performed only once a year. Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis comprises only the five Ordinary portions. So why does he title it Missa Solemnis?

By the latter part of the eighteenth century, the term had come to stand for any mass setting which was particularly elaborate, or longer than average; Beethoven’s title is best understood in this sense of the term. It can last anywhere from 71 minutes (John Elliott Gardner) to 83 minutes (Herbert von Karajan)-- too long, practically speaking, for liturgical performance; it utilizes a very large orchestra (by the standards of the early nineteenth century) and chorus, as well as soloists; and it features expressive language and devices which would overwhelm a worship service, even if it were not so long.

Beethoven was raised a Roman Catholic. His grandfather was kapellmeister and bass singer at the electoral court in Bonn; his father was a court tenor. As a child, growing up in this environment, Beethoven would naturally have assumed that he would one day hold a kapellmeister position himself, and compose music for the church. Things did not work out that way for him; and as an adult he was not a regular church-goer, and was fundamentally opposed to a social order in which ordinary people were expected to defer to any sort of higher authority, including ecclesiastical authority. He composed very little sacred music—and the two works preceding Missa Solemnis, Christ on the Mount of Olives and Mass in C, lack the weight and importance of other of Beethoven’s works which are contemporaneous with them, such as the Eroica and Pastorale Symphonies. He did not actively oppose the Church, or Christianity in general; he just was not very interested, at least through most of his life. Commentators suggest that he experienced a spiritual crisis around 1819—that he finally needed to come to terms with God and with his spiritual life, which he had largely put to the side, up to that point. German music critic Paul Bekker wrote:

“Beethoven’s new material was the poetry of transcendental idealism. He abandons such symbols from the visible world as he had used in the Eroica and succeeding works, and turns toward the invisible, the divine…the Mass became the second great turning-point of his art, as the Eroica had been the first. The third symphony embodies the ‘poetic idea’ to which Beethoven was groping in preceding works; the Mass presents the same idea, transfigured and spiritualised. Freedom, personal, social and ethical, is consecrated and raised to heights where every activity, even of an apparently earthly kind, is flooded with unearthly light.”

Beethoven began composing the Missa in the spring of 1819, upon learning that one of his most important patrons and students, Rudolph, Archduke of Austria, was to be made Archbishop of Olmütz, in Moravia. Rudolph was one of the most generous and reliable of Beethoven’s patrons during the final twenty years of his life, and the composer dedicated many major works to him. He told Rudolph of his planned presentation in a letter of June, 1819, and hoped that the mass would be performed during the installation ceremony. The work grew to be larger and more complicated than he had anticipated, however, and he missed the date of the installation (March 9, 1820) by more than three years! There seems little doubt, however, that his friendship and regard for the Archduke were sincere, and that, whatever else he hoped to gain, he intended the work as a gift of heartfelt appreciation; his inscription at the head of the score: “von Herzen—möge es wieder—zu Herzen gehn!” (May it go from the heart to the heart!) seems to apply to his relationship with the archduke, as well as to his audience. There is some indication, as well, that Beethoven hoped, even expected, to become the Archbishop’s kapelleister, though this expectation was never fulfilled.

Romain Rolland wrote that Beethoven had “a great need to commune with the Lamb, with the God of love and compassion,” but the Missa Solemnis “overflows the church by its spirit and its dimensions.” Beethoven’s personal regard for Rudolph did not lead him to exercise any sort of submission to the Catholic Church as a whole. The work is not a good fit for either church or concert hall; Beethoven himself, on several occasions, called it “a grand oratorio,” and its first full performance, in St. Petersburg, was as an oratorio, rather than as a vehicle for worship. He presented the Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei in May, 1824, in Vienna’s Kärntnertor Theatre, under the title “Three Grand Hymns with Solo and Chorus Voices.” And he offered to provide the Bonn publisher Nikolaus Simrock with a German-language version, to facilitate performance in Protestant communities.

But these various particulars do not diminish the religious significance of the work. Beethoven later wrote, “My chief aim was to awaken and permanently instill religious feelings not only into the singers but also into the listeners;” and in a letter to Archduke Rudolph, he wrote, “There is nothing higher than to approach the Godhead more nearly than other mortals and by means of that contact to spread the rays of the Godhead through the human race.” He seems to stress, here, a special, personal (read, Protestant) relationship with God, as opposed to the hierarchical relationship so important in Catholic polity and theology.

Beethoven clearly intended to make money off the work, as well, and was not above manipulating the market for maximum profit. William Drabkin writes, “The steps [Beethoven] took to sell the work are likewise exceedingly complex, and they do not reveal the composer in the best light as a human being.” Already in 1820, years before the Missa was completed, he reached an agreement with Simrock for the publishing rights, and was paid a generous advance. Two years later, when the work was completely sketched out, Beethoven secretly agreed to sell it to C.F. Peters, in Leipzig, for a higher fee yet. And as completion of the work approached, he entered into negotiations with Artaria and Diabelli in Vienna, Schlesinger in Berlin, H.A. Probst in Leipzig, and B. Schott’s Sons in Mainz. Finally, in 1825, he agreed to give it to Schott, presumably for the highest bid. Simultaneously, Beethoven sent invitations to important personages to subscribe to hand-written copies of the Missa; ten copies were made and sent out in response, in 1823. (As one can imagine, so complicated a publication and distribution history, along with the fact that proofreading and publication coincided with Beethoven’s final illness and death in 1827, contributed to a number of textual problems which have never been resolved.

This, then, is the background upon which the performers build their performance.

Tackling the Missa Solemnis

Northern Light and Thanksgiving break behind us, Chorale embarks now on a terrifying but exhilarating adventure—Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, reputed to be the most difficult work for singers in the standard repertoire

Northern Light and Thanksgiving break behind us, Chorale embarks now on a terrifying but exhilarating adventure—Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis!

The Missa is reputed, among singers-- soloists and choristers alike-- to be the most difficult major work in the standard repertoire. Beethoven expects his singers to sing for long periods of time at the extremes of their capacity-- very high and very low, very loud and very soft, very fast and very slow. He seeks always to extend the expressive possibilities in music-- and rarely lets singers feel comfortable. Palestrina, Handel, and Mozart are far easier on the voice and the intellect, and more gracious to sing—these composers seem to know and like the human voice, as well as the expressive and intellectual capacities of singers, and always make allowances for difficulties performers might encounter; singing their music, even their choral music, is almost like singing vocalises chosen by good teachers, to help maximize ones potential for tonal beauty and efficiency, as well as give one the framework for heartfelt expressiveness, free of the anxiety which is likely to make singers “clutch.” Even at their most dramatic, these composers prepare their crescendos and decrescendos, provide lots of support in the orchestra for difficult pitch changes and high notes, and never leave singers at their fatiguing extremes for very long.

Beethoven, on the other hand, is likely to leave a singer, or singers, on a high note for several measures in a row, at a continuous forte or fortissimo, and then suddenly require a pianissimo in another range entirely, arrived at by an awkward leap reflective of an unexpected harmonic modulation, with no doubling in the orchestra. Not content to establish and then maintain a single tempo for the duration of a particular line of text and its musical setting, Beethoven, in the “Et vitam venturi, Amen” fugue of the Credo (bars 306-472), requires three: Allegretto, Allegro, and Grave—and at the Grave (the slowest tempo in the entire Missa, up to this point), the choral voices sing at the highest extremes of their vocal ranges, at a forte volume level, with no fewer than seven sforzando accents in the course of five measures. This, immediately after 126 measures of very demanding fugal coloratura.

Beethoven presents his performers with challenges that are physical, aural, and philosophical-- his works are difficult to imagine and encompass, from beginning to end, and singers who are not accustomed to singing them have a hard time just getting up the nerve to dive into them with any confidence. As one would expect, Chorale’s singers are not particularly cowed by the metaphysical content of the work-- they are highly educated people, accustomed to grappling with difficult intellectual problems, and their relative success in the demanding professions they have chosen gives them confidence in confronting new and otherwise daunting challenges. The response of individuals with whom I spoke, after our first rehearsal on the work, two weeks ago, was upbeat, excited, even cocky; I did not hear much fear or dread in their voices. As time goes on, though, they will come to realize, on the most visceral level, that Beethoven demands far more than metaphysical understanding and appreciation-- he requires muscle, sinew, blood, and tears.

Chorale is up to eighty-five singers for this program—at least twenty-five more than we usually have. We will be joined by forty singers from the chorus sponsored by the Symphony of Oak Park and River Forest, prepared by their regular chorus master, Bill Chin, for a final ensemble of 125-- a good size for this work, one that will balance the orchestra, and sound good in Symphony Center, where we will perform it. We are somewhat crowded in our rehearsal hall, Hyde Park Union Church, but have been experimenting with seating arrangements, and are approaching a workable solution. Enthusiasm, and the recognition that we are performing a fantastic program, will go a long ways toward easing our discomfort.

Missa Solemnis is not often performed, despite its position, along with J.S. Bach’s Mass in B minor, as one of the two greatest settings of the Mass ordinary. I suspect this is more because it is so very difficult to mount, rather than because audiences are uncomfortable with it. Performances in which I have participated have never failed to elicit an over the top response from the audience. We are thrilled to present it, and thrilled to have such able partners in this venture, in the Symphony of Oak Park and River Forest, under the baton of Jay Friedman. We have many weeks of hard work ahead of us (the concert is March 5), and and even then we will depend upon the peculiar spirit of Beethoven to carry us over the top.

Advent Vespers at Monastery of the Holy Cross

The event bears little resemblance to Advent and Christmas commemorations one is likely to find elsewhere in our area. Far from feeding the listeners’ desire for excitement, comfort, or nostalgia, the liturgical framework, the music, and the chapel building itself (one of the best acoustic spaces in the region) inspire reflection, soul-searching, and a sense of timeless peace.

Chorale opted for an Autumn concert this season, rather than a Christmas concert. Competing with all the other performing groups out there, plus other holiday-related activities, can really wear a group (and its management) down. Promotion, always a major expense and energy-drain, becomes enormously costly when aiming for the holiday crowds; and even when one puts in the money and the work, a group still loses singers, as well as audience, when so much is going on. There are pluses and minuses to jumping into the holiday fray; after ten years of doing so, Chorale tried something different. And we were immensely gratified by the success of our Northern Light concerts: unfettered by seasonal concerns, we were able to program a new, unusual, and sophisticated repertoire, and our audiences were large and enthusiastic. Just as important, from a programming point of view, we had sufficient preparation time, and now have an additional three weeks in which to rehearse our winter concert, before the holiday break hits.

But we do not ignore the season altogether. Each Advent, a subset of Chorale’s membership participates in an Advent Vespers liturgy at the Benedictine Monastery of the Holy Cross, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. Far from being a “holiday celebration,” the vespers liturgy is a living, cyclical aspect of monastic life, and features concerted music at those points for which it was originally composed, rather than as “concert music.” At Holy Cross, both monks and choir sing in a mixture of Latin and English, and the repertoire ranges from Gregorian psalm tones to complex, highly sophisticated choral polyphony. This year’s repertoire includes service music and motets by Victoria, Byrd, and Palestrina, all composers active at the close of the sixteenth century. At several points during the service, Chorale and the monks will sing antiphonally, taking alternating verses of the psalmody and the Magnificat.

The event bears little resemblance to Advent and Christmas commemorations one is likely to find elsewhere in our area. Far from feeding the listeners’ desire for excitement, comfort, or nostalgia, the liturgical framework, the music, and the chapel building itself (one of the best acoustic spaces in the region) inspire reflection, soul-searching, and a sense of timeless peace—the moment one enters the chapel, one becomes a participant in something older and more sacred even than Christianity itself: the mystery of the numinous, in sharp juxtaposition to our daily cares and concerns. The monks enter quietly, each at his own pace and in his own way, yet all of them similar in their lack of hurry, lack of concern, lack of tension; those who come to listen and participate from the pews, as well, seem to leave off their hustle and bustle as they enter the space, and sit quietly, without impatience, as the liturgy unfolds. We musicians learn our music in advance, with appropriate tension, fear of failure, concern for correctness and stylistic appropriateness-- then we, too, succumb to the ritual of the liturgy, the unfolding of the event, as one rarely does when singing for an “audience.”

People do not beat down the doors to attend this Vespers; there are no posters, no advance ticket sales, no reservations, no ushers to seat you. The monks, and Chorale, have enough of a following that the chapel is comfortably occupied—but even this doesn’t seem to matter: the glory of this music, sounding as an integral part of this liturgy, at this particular season, has beauty and purpose and life on its own. One senses that the world changes, is quietly shocked into a better place, through this “incarnation,” this focusing of our gifts during this ritual, whether anyone hears it or not. I personally find myself upheld in profound, quiet beauty , supported and nourished by the totality of the experience-- I am sorry to leave the building afterward, to reenter Advent and Christmas and the business of music as we know it; I linger until the monks finally nudge me out the door, telling me they have to be up and functioning early the next morning and need their sleep.

I tend not to invite friends to this event. I fear the austerity and simplicity will disappoint them, and that their disappointment will stand between them and the experience itself. I expect that people who know what they are in for, will come, and that that is enough. Then, each year, after it is over, I am sorry I did not let people know-- so, consider yourselves invited. Sunday, December 4, 5 p.m., Monastery of the Holy Cross, 31st and Aberdeen on Chicago’s South Side.

A review of our Northern Light concert!

Chicago Chorale soars in Baltic and Scandinavian music.

Sat Nov 19, 2011 at 4:31 pm

By Lawrence A. Johnson

Chicago is home to such a plethora of fine choral groups that it’s sometimes hard to keep track of them.

Add the Chicago Chorale, now in its 11th season, to the roster of local ensembles that deserve to be much better known. Led by artistic director Bruce Tammen, the ensemble presented “Northern Light,” a concert of 20th-century Scandinavian and Baltic sacred music Friday night at Hyde Park Union Church that for stylistic variety, polished vocalism, and depth of expression was a success across the board. (The program repeats 8 p.m. tonight at St. Vincent de Paul Parish in Lincoln Park and should not be missed.)

The level of execution would have been impressive even coming from a professional chorus. Yet Tammen’s singers are largely non-pros. There is a scattering of professional singers and music teachers but the 61 chorus members’ occupations range from bookstore manager to physicist, banker, psychiatrist and interior designer. Perhaps some of the solo singing from chorus members wasn’t quite on the same level as the ensemble yet under Tammen’s dedicated direction the multivaried components largely sang as a single organic whole.

Tammen’s calisthenic-like conducting style is somewhat unorthodox but he certainly gets results. In his brief introduction, Tammen joked that, being of Norwegian extraction, he took “full responsibility for this program,” and that affinity for this repertoire was clear in the bracing and idiomatic, often stunningly beautiful performances.

The largest work on the program was also the best known, Grieg’s Four Psalms (Fire Salmer). Written near the end of the Norwegian composer’s life, these settings are his final masterpiece, closely wrought and imbued with a glowing yet clear-eyed and unsentimental expression.

The Chicago Chorale singers brought out the spiritual glow ofHvad es du dog skjon as well as the buoyant carol-like Guds Son har gjort mig fri with striking corporate finish and assurance. The meditative spiritual feeling of Jesus Kristus or opfaren was especially well done. The performance benefited greatly from baritone soloist Michael Cavalieri whose rounded tone and poised, flexible expression could not have been more communicative.

Tammen’s program was both ambitious and adventurous taking us from Grieg up to Arvo Part. Yet his singers assayed the various challenging languages, including Norwegian, Swedish and Estonian, with extraordinary clarity and what sounded (to non-expert ears) like genuine idiomatic engagement.

The performances of the avant-garde works of Knut Nystedt were especially impressive. The Norwegian composer’s take on Bach’s Come, sweet death (Komm, susser Tod) conveys the somber beauty of the setting, here with the four sections of the chorus each deftly directed not by Tammen but by individual section leaders lending a spontaneity (and danger) to the music before a final homophonic reprise.

Jan Sandstrom’s Gloria is a small masterpiece of choral minimalism, and the group’s performance brought out the Swedish composer’s luminous beauty with a fine solo contribution by pure-voiced soprano Kaela Rampton.

The Chorale’s sopranos handled the mercilessly exposed writing of Nystedt’s Audi and O crux with aplomb, Tammen ensuring clarity in the overlapping writing, quick crescendoes and dizzying multipart writing. Three challenging excerpts from Rautavaara’s Vigilia showcased the folk-like flavor.

Arvo Part’s Bogoroditse Djevo is an atypical piece for the monastic minimalist, fast and carol-like in its folky cheer and received a fresh and lively reading. Music of a younger Estonian Urmas Sisask, closed the evening with a Benedictiothat built from alternating subterranean basses and high-flying soprano lines into a bravura showpiece, thrown off with great fervor, corporate polish and huge panache by Tammen and the Chicago Chorale.

Piteå and Sandström

Sommarmusik i Piteå was one of the most interesting musical experiences of my life.

In June-July 1988 I participated in a music festival in Piteå, Sweden, a small town at the very top of the Baltic which happens to have a prominent “folkhögskola” (literally, folk high school), committed to the teaching of music, and which is very close the coastal resort town of Luleå. Sommarmusik i Piteå turned out to be one of the most interesting musical experiences of my life. Piteå is up there—above the Arctic Circle; the sun never really set during the course of the festival, and the midsummer partying for which Scandinavians are famous was an important part of the festival offerings. I was the only American participant, aside from the master vocal coach, Dalton Baldwin—which was not a problem, linguistically: everyone there spoke decent English, and my tortured attempts to speak a hodgepodge Norwegian/Swedish were greeted politely and patiently. We slept in dormitories (the windows had black-out blinds, to create the illusion of dark night), ate in the student cafeteria (herring, reindeer, flatbread and cheese were always on the menu), attended concerts most evenings, and had plenty of time to swim, hike, and explore the town. The mosquitoes were terrible—worse than in Minnesota; people wore long pants, long sleeves, gloves, and interesting mosquito nets, which they draped over their heads.

By day we participated in master classes. The singers were from all of the Scandinavian countries, and presented primarily the standard repertoire—French, German, Spanish, American English—of which Dalton is a noted interpreter. I was the only singer who brought Scandinavian song—Grieg, Stenhammar, Sibelius—and was coached primarily by the other students when I had the temerity to sing it. As a group, these were some of the best young voices I have ever heard—strong, clear, solid, well-schooled. They could do everything a voice should be able to do. Dalton agreed about the physical quality of the voices, but felt the singers lacked imagination, warmth, fantasy, mystery-- he was hard on them. Following the festival, I flew with him down to his summer program in Nice, and thought a lot about his criticism-- indeed, the singers in the latter program were more daring, more individual, also more obviously egotistical and outrageous; many lacked the solid vocalism of the Scandinavian singers, but seemed to make up for this lack with color and shading, rubato, dramatic expressiveness. Really, I thought, this is apples and oranges—and I still feel that way. Nordic musical composition and performance has its own beauties, its own expressiveness, promotes gasps of wonder and delight in its own way.

While we singers worked in one part of the campus, instrumentalists, composers, pianists worked with their own master teachers, in other locations. We saw little of one another. So I did not realize, until some years later, that Piteå and its School of Music were and are the home base of Jan Sandström (born 1954), one of Sweden’s most noted composers. Like other Swedish composers of his generation, he began his compositional career writing in an austere, theoretical, sophisticated, densely-constructed idiom—in his case, making using of spectral techniques (composition based on analyses of overtone registers); it wasn’t until the late 1980’s that his voice began to veer toward something more emotional, playful, gentle, even naïve—an exploration of ordinary people, ordinary feelings, of living in the moment—as he has written, “Every morning when I wake up, I want to be surprised by whatever I might think up today!”

These later characteristics are on display in the Sandström composition Chorale will perform on its coming concerts. Gloria (1995) is one movement of a mass in progress, dedicated to the orphanage of “La Casa de la Madre y el Niño” in Bogota, Columbia. To my ears, this piece reflects much the same sensibility as works by spiritual minimalists Tavener, Pärt, and Górecki, though with less brooding darkness and mystery. The listener must put the rush of life to one side, and listen patiently, allow the gently repeated musical cells, the simple diatonic harmonies, the silences, to take over and lead where they will. One critic has written that Sandström composes “music that pats you on the hand and says ‘there, there, it’ll be all right’”—a significant journey from the music he composed earlier in his career.

As I am with all of the minimalist music I program for Chorale, I am slightly uncomfortable with this work-- I have a hard time with simple, uncomplicated statements and the silences between their repetitions; J.S Bach is my favorite composer—I like “too many notes.” I tend to feel that the bones, the structure, harmonically, rhythmically, dramatically, liturgically, should be so strong that they stand by themselves, with or without a great performance—that they indeed can make a performance, and a performer, great, by providing a worthy structure. Minimalism seems to require great performers doing a great job at doing very little—only through a great performance can the elusive beauty of such music succeed, and not be weighed down, broken, made maudlin, by less than perfect execution. Thoughtful, talented composers are writing this music; I want to support them on their journey and see where it leads. I see little sense in re-tilling worn-out soil; so I help with the planting of seeds in new ground, and hope to like what comes up.

One thing I can say: Sandström’s music does indeed reflect the tundra and mountains of Lapland, the northern place out of which it springs. The simplicity, the silences, the fearful devotion, seem very apt when I think about my time in Piteå—a short, brilliant summer, followed by a very long and dark winter.

The Singing Revolution

The Estonian composers featured on our upcoming concert program, Arvo Pärt and Urmas Sisask, reflect, each in his own way, The Singing Revolution, a series of politico/musical events which were instrumental in restoring the independence of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1991.

The Estonian composers featured on our upcoming concert program, Arvo Pärt and Urmas Sisask, reflect, each in his own way, The Singing Revolution, a series of politico/musical events which were instrumental in restoring the independence of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1991, after more than fifty years of Russian rule. Beginning in 1987, Estonians gathered in spontaneous mass demonstrations, by the hundreds of thousands, to sing national songs and hymns, which were forbidden by the Soviet authorities, while Estonian rock bands played. Eventually, these events served as opportunities for political leaders to work up the crowds, which often numbered more than 300,000 people, one quarter of all Estonians. After more than four years of this, Estonia proclaimed its independence, on August 20, 1991, with no blood having been shed.

The Estonian composers featured on our upcoming concert program, Arvo Pärt and Urmas Sisask, reflect, each in his own way, The Singing Revolution, a series of politico/musical events which were instrumental in restoring the independence of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1991, after more than fifty years of Russian rule. Beginning in 1987, Estonians gathered in spontaneous mass demonstrations, by the hundreds of thousands, to sing national songs and hymns, which were forbidden by the Soviet authorities, while Estonian rock bands played. Eventually, these events served as opportunities for political leaders to work up the crowds, which often numbered more than 300,000 people, one quarter of all Estonians. After more than four years of this, Estonia proclaimed its independence, on August 20, 1991, with no blood having been shed.

Arvo Pärt, born in 1935, was not even in Estonia during this period. After years of struggle with Soviet authorities, he had already emigrated to Vienna with his family in 1980, and moved from there to Berlin. He returned to Estonia in 2000, and has lived there since, a symbol of his nation’s triumphant struggle, revered both for his international musical prominence and for his resistance to pressure from the Soviet regime. His compositions do not reflect specifically Estonian themes or procedures—it seems clear he thinks of himself as a world-citizen, as inheritor of the entirety of the European musical tradition; throughout his career, he has immersed himself in Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony, and has reinterpreted these musical roots through a personal, minimalist language characterized by simple harmonies, static rhythms, and narrow melodic arches. He composes for a wide variety of instruments and in a wide variety of genres; his choral music consists almost entirely of settings of sacred texts in Latin or Church Slavonic. This choral music is immensely popular in Estonia, as it is throughout the world.

Urmas Sisask was born in 1960, and represents the very generation most involved in, most affected by, The Singing Revolution. While Pärt was living in Vienna and Berlin, Sisask studied and worked in Estonia; since 1985 he has lived and worked in the small town of Jäneda, where he has conducted a choir, taught, and pursued his passion for astronomy, which is reflected in his compositional ideas and techniques. His works are also influenced by an interest in shamanistic cultures and ancient Estonian song. He utilizes short, core melodies, or cells, which he repeats over an ecstatic rhythmic pulse, with small variations and a constant building of intensity, in a manner which suggest medieval dance music and ancient shamanic rituals, as well as Estonian folk music.

I found this through Google: “Universe was created with love 13,7 milliards years ago. Stars, galaxies, planets, comets and other cosmic beings, including us, exist happily in great love. Human beings were created here to sense the love. Planet Earth is a magnet to life. Human being is born of stars and becomes to stars as well. Therefore I don't regard myself as a composer, rather transcriber of music.” (Urmas Sisask)

This mystical overview of existence is somehow obvious in his choral composition: he expresses directly, simply, powerfully, with great energy, but without much self-consciousness or circumspection. He just lays down the notes. In Estonia he seems to have nearly rock-star status: he has been awarded the Cultural Award of the Republic of Estonia (1990), the Order of the White Star (Fourth Class) (2001), the Armorial Order of Järvamaa County (2001), the Estonian Defense Forces Special Service Cross (2004), Veljo Tormis’s Estonian Choral Music Grant (2007) and the Estonian National Culture Annual Award of Pro Patria and Res Publica Union (IRL) (2009), title of Musician of the Year of Estonian Radio (2010) and Annual Prize of the Culture Endowment of Estonia (2010). YouTube videos show ecstatic teenagers at outdoor gatherings which include thousands of singers, singing his music with their arms around one another, much as the scenes of the late 1980’s are described.

Norwegian language coaching

Chorale’s Norwegian language coach, Jone Hellesoy, began her first session with us, on Grieg’s Fire Salmer, with a disclaimer: Norwegian is not a unified language, and there is no one way to pronounce it.

Chorale’s Norwegian language coach, Jone Hellesoy, began her first session with us, on Grieg’s Fire Salmer, with a disclaimer: Norwegian is not a unified language, and there is no one way to pronounce it. She described Norway’s topography for us: small villages in remote valleys and along isolated fjords, historically separated from one another, each with its own dialect or pronunciation. This, together with Norway’s political history—centuries of domination by both Denmark and Sweden-- has left the country with a tangled linguistic map. Jone did not, as some writers will do, predict a future in which the various strands of the language would finally coalesce, organically, into a single language—rather, she told us we should choose one particular pronunciation—that of Oslo and the east coast—and stick with that. And she then zinged us—she told us that she, herself, speaks a southwestern dialect, which includes a uvular [r] rather than the flipped [r] we want for singing, and that she cannot flip an [r]—we would just have to imagine it!

As we got into our texts—a series of hymns written over the past several hundred years—Jone often found herself stumped, both by the meanings of the words and idioms, and by their pronunciation. She would say, “This is a Swedish word,” or “I think this is a Danish expression,” and sometimes she would declare, with exasperation, “I have no idea what this word is, or what it should sound like.” As I mentioned in my September 28 blog, I have two recordings of the Grieg, one by a Danish choir, one by a choir from Olso, each pronouncing according to its own national rules; where Jone is in doubt, we follow the Oslo recording—presumably, they either know what they are doing, or have made some acceptable, arbitrary decisions.

Mainly, and importantly, what we got from Jone is a sense of the overall sound—how the vowels are formed, how the consonants (with the exception of [r]) are articulated, how diphthongs and off-glides are handled, the character of the phrases-- the ups and downs, the peculiarly musical quality which lends itself to a typical two-bar phrasing—and the “color” of the overall sound. This is invaluable, and speaks strongly in favor of working with an actual native speaker-- it would be good to hear her reading our texts, more often!

Language is fluid and constantly changing, constantly varying; for the purposes of choral performance, however, we need a somewhat “frozen” standard, in order to satisfy our need for uniformity and purity of sound. When I have sung with Stuttgart’s Gächinger Kantorei, I have been surrounded by singers who come from all over Germany, and bring with them their own, very distinctive accents and dialects; were they to pronounce sung German with these accents, the result would be worthless. A single, knowledgeable singer is nominated to correct pronunciation—all variants are referred to him, and he corrects them, unifies the group’s presentation. Germany is fortunate in having a recognized standard, as are other, major European countries, like France and Italy-- “classical” singers are trained to utilize this standard, and it is recognized world-wide. French for instance is spoken with a bewildering range of accents, world-wide; but a trained singer would not sing Debussy with a Haitian or Vietnamese accent.

American singers study the “lyric diction”of these languages as a matter of course, and often become remarkably skilled at singing in languages which they don’t in the least understand. A study of recordings from the beginning of the twentieth century to the present shows that even these artificial “standard” pronunciations change over time-- but very slowly, and in aspects to which singers easily adapt. Smaller, more out-of-the-way countries like Norway, however, have neither the population, nor the international cultural impact, to require, for purposes of export, the imposition of a standard—so when a composer of international stature, like Grieg, comes along, his vocal music, though of very high quality, can easily be neglected. Grieg himself, knowing this, published most of his choral music and songs with alternate, singing German translations-- but, like any first rate composer, he is too accurate and skillful in the presentation of his own language, to be easily and smoothly translatable—something just sounds “wrong” when he is sung in German or English.

Chorale, as a central part of its mission, sings wonderful but out-of-the-way music. Inevitably, this requires that an inordinate amount of time be spent with language. Part of our audition process focuses on the singers’ ability to reproduce, accurately, the sounds of a foreign language. We are fortunate that our singers tends to be highly educated, and interested in the challenges with which they are confronted-- our ambitions would be unrealizable, were they not so!

A tour through Northern Light territory

Chorale’s current repertoire falls into three rough categories, with all kinds of overlap.

Chorale’s current repertoire falls into three rough categories, with all kinds of overlap. The first, and earliest, category, described in my previous blog entry, is the National Romantic style-- indigenous materials presented through the vocabulary and procedures of German Romanticism. One has only to turn on WFMT radio and listen for an hour, to realize how pervasive German music is in our “classical” music culture: from Bach through the Viennese classicists to Mendelssohn, and then, especially, to the overpowering influence of Wagner, this national style became THE international style of the 19th and early twentieth centuries. Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg received his training in Leipzig; valuable aspects of that German matrix stayed with him throughout his career, and influenced, as well, the Scandinavian nationalists who followed him: Stenhammar, Sibelius, Nielsen come immediately to mind. One of the works on our program, though decidedly modern and not otherwise representative of this genre, is a conscious homage to the influence of Bach and German common practice: Komm süßer Tod utilizes a musical phrase by Bach, harmonized by Knut Nystedt, then choreographed by Jan Sandström.

At its worst, Romantic Nationalism is cute, nostalgic, and manipulative, begging to be performed in national costume; at its best, it combines disparate materials into a powerful, sincere expression which transcends national boundaries, taking its place as a legitimate body of work. The motets on our program most clearly representative of this genre—Grieg’s Fire Salmer, Lindberg’s Den signade dag, Olsson’s Jesu dulcis memoria—share a dark, somber coloration, relieved by moments and phrases which seem to leap from the dark with startling brightness and warmth; they are couched in a rich harmonic palette, augmented both by 20th century approaches to dissonance and by the ancient, modal background of their source material; they combine dramatic, vocally challenging phrases and tessitura with typically short, two-bar rhythmic cells, suggestive of folk dance; and they awaken both a sense of loss, and of yearning, in the listener.

Knut Nystedt (b. 1915) represents, and perhaps first explored, our second category, something I call “Nordic Minimalism.” Typical of minimalists in general, and of the Spiritualist Minimalists (Tavener, Pärt, Gorecki, for instance) in particular, Nystedt backs off from much of the structural and harmonic complexity of 19th century composition, and uses simpler materials, as well as a certain static harmonic and rhythmic quality, to create an icon-like music, through which the listener perceives underlying spiritual meaning. Nystedt has been a prolific composer, and his output is uneven in quality; his best works, represented in our program by O Crux and Audi, echo the deep, yearning romanticism of Grieg, as well as the mysticism of Nystedt’s religious faith, and, in common with so much nordic art, effectively mirror the northern landscape which inspires them—the mountains, the sea, the glaciers, the seasonal extremes of darkness and light, the terrors and beauties of a hostile but beckoning world. Jan Sandström, a Swedish composer of the following generation, clearly owes a lot to Nystedt’s influence, but is more minimalist in style-- the Gloria which we will perform is almost a textbook example of discreet, simply conceived cells, repeated with minor variation, building and then subsiding in a consciously non-dramatic fashion. His kinship with Polish minimalist Henryk Górecki (1933-2010) is unmistakable.

East and south across the Baltic something very different has happened, chorally. The Baltic countries, as well as Finland, were influenced at least as much by Russian as by German culture; and their national struggles, which find powerful expression through their choral music, have led them in a far different direction, than that taken by their counterparts in western Scandinavia. This third category is represented in our program by music of Rautavaara, Pärt, and Sisask.

Finland, long a cultural vassal, first, of Sweden, then of Russia, found and established, largely through the compositional journey of Jan Sibelius, its own musical voice and expression later in the twentieth century than did Norway. Finnish choral music sounds eastern to our ears, less “square” and Lutheran than the music on the western side of the Baltic. Filtered through both Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions, it lacks some of the rich harmonic language of German Romanticism, but explores a far broader and more percussive rhythmic palate. Finn Einojuhani Rautavaara, represented on our program by three movements from his Vigilia, composes in an especially colorful, exotic style, with elements drawn from ancient Byzantine liturgical practice as well as from folk music of rural Finland. Bogoróditse Djévo, by Estonian Arvo Pärt, perhaps the best-known of the spiritual minimalists, reflects its composer’s Orthodox faith and mystical practices through repetition of simple musical cells, expanding and contracting according to the needs of the liturgical text. The piece is surprisingly short, for Pärt, clocking in at only one minute, but beautifully, efficiently composed. His younger Estonian colleague, Urmas Sisask, composes in a superficially similar style, but clearly has a very different musical personality and goal-- he sets the Latin text of his motet, Benedictio, “We praise your power, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost,” in an incantatory style, utilizing the repeated cell procedure to build to enormous, exciting climaxes, and manipulating his underlying rhythms—rhythms that would simply be inconceivable in Norwegian or Swedish music-- catching his listeners (and singers!) off balance, generating melodic arches both thrilling and frustrating in their angularity. This work, composed in 1996, clearly flies free of German and Russian influence, and forms a bridge to the twenty-first century.

Edvard Grieg, Opus 74-- Fire Salmer

Chorale describes its Northern Light concert as focused on twentieth century music. Our earliest composer, Edvard Grieg (1843-1907), barely makes it under the wire.

Chorale describes its Northern Light concert as focused on twentieth century music. Our earliest composer, Edvard Grieg (1843-1907), barely makes it under the wire. Most of his compositional output is 19th century, and sounds like it—as a young man, he studied the German Romantic tradition in Leipzig, and was particularly influenced by the music of Robert Schumann; he is generally listed as Late Romantic. In the past few years, though, the category “National Romanticism” has come more and more into vogue, and allows for the inclusion of a lot of music and composers-- for instance, Rachmaninoff and other, lesser-known composers of the Moscow Synodical School; Dvorak; Smetana; Vaughan Williams and other English “pastoralists”—which had previously been relegated to a dusty corner of academia reserved for stubborn anachronists who just weren’t up to the revolutionary explosions inaugurated by Schoenberg and Stravinsky. Grieg can arguably be described as the inventor of Nordic National Romanticism-- after his years in Germany, he returned, first to Demark, then to Norway, with the express purpose of forming a serious, high-level national music, both instrumental and vocal, from materials found in Norwegian folk music-- melodies, harmonies, rhythms. Content with his role as a composer and performer of “small” pieces, he wrote hundreds of songs and piano works which are characterized both by their “nordic-ness” and by their authentic personal voice-- Grieg had something very individual to say, and he found new and inventive ways to say it, right up to his death.

Grieg’s Fire Salmer (Four Hymns), Opus 74, for baritone soloist and mixed choir, was his final composition, composed in the second half of 1906. He adapts melodies from L.M. Lindemann’s collection Older and More Recent Norwegian Folk Tunes, an anthology upon which he drew heavily throughout his career. Like much of his later music, these motets are particularly notable for their harmonic inventiveness: he is very adept at adapting the modes of his source material—neither major nor minor—and at harmonizing it in a manner which sounds and feels authentic, rather than somehow contrived or “colorful.” There is nothing about these four motets which inspires nostalgia or “pining for the fjords”-- rather, they have a conciseness, urgency and drive which earns them a place with the finest choral compositions of their time. In one of the motets, Guds Søn har gjort mig fri, the soloist sings in a straightforward B flat Major tonality, while the men of the choir accompany him in a constantly shifting and disturbing version of b flat minor—and Grieg handles the resulting clashes so confidently, one never questions either his skill, or the result.

Like Brahms, Grieg grew up in a Lutheran milieu, a member of the Lutheran state church; also like Brahms, he was not very comfortable with the tradition, often treating it, musically, with a kind of ambivalence which is very far removed from the religious fervor of such contemporaries as Anton Bruckner and Max Reger. His setting, in the first motet, Hvad es du dog skjøn (How beautiful you are), of a paraphrase from the Song of Songs, is passionately secular and sensual in nature; and his text painting in the third motet, Jesus Kristus er opfaren (Jesus Christ is risen) is anything but triumphant or rejoicing. Altogether, Grieg’s responses to his source material, with which his intended listeners were intimately familiar, is surprising, subversive, and almost painfully personal. I expect he felt he had nothing to lose, that pursuing his personal vision was what he had left to him—as he wrote in his diary during the period of Opus 74’s composition, “These small works are the only thing my wretched health has allowed me…The feeling ‘I could, but I cannot’ is heartbreaking. In vain I am fighting against a superior force and soon, I suppose, I shall have to give up completely.” And indeed, he died just one year later, ten months after their completion.

The language of the texts is an interesting puzzle in itself. Called “Bokmål” or “Riksmål,” it is actually more Danish than it is Norwegian, and reflects the centuries during which Norway was, effectively, a colony of Denmark, with Copenhagen as its governmental and cultural center. Written texts fostered by the state church, such as those in these hymns, would have been in bokmål, as would all government documents—really, anything written down (bokmål means “book language”). Norway did not gain its political independence until 1905, only two years before Grieg’s death—but Grieg was an active, inspiring voice in the development of Norwegian nationalism, and helped focus attention on the development of an indigenous Norwegian language. In much of his vocal music, he sets texts in “Nynorsk,” an invented language which is actually an amalgam compiled of dialects from throughout the country, and which has become one of the two official languages of Norway since that time. Bokmål did not die out, however— it continues to this day, but is pronounced with a distinctively Norwegian accent, which differentiates it from Danish, which it resembles on the page. I have two very good recordings of Opus 74, one by a Danish choir, one by a Norwegian choir-- each choir sings the same words, but with its native pronunciation—how strange! Chorale is learning the Norwegian pronunciation.

Grieg sets text beautifully. Much of his best compositional output is found in his vocal music—he composed hundreds of songs, and toured with his wife, a soprano, presenting concerts with her of his music. Many of these songs were translated into German when they were published, but are far better and more expressive in Norwegian-- he clearly loved his own language. I expect that the relative obscurity of the language has kept both the songs, and these motets, from becoming well known—which is a loss; this is profound music. It will be a struggle to learn these works—but I have no doubt both singers and members will be immensely rewarded.

To Battle! Ludwig Wicki conducts The Lord of the Rings

Wicki has to deal with a merciless time corset: The music has to match the movie exactly - preferably to the centisecond. The consequence: minimal freedom, maximal concentration.

The following appeared in the Munich newspapers last week, relative to a showing of the second film in the LOTR series, "The Two Towers."

After conducting The Two Towers, Ludwig Wicki feels as if he had fought in the battle of Helm’s Deep. Winded, exhausted. But happy, for he is victorious. It’s an almost Herculean exertion to perform The Lord of the Rings live: the movie is shown on a huge screen, but without the music, which is played by Wicki live and in color – along with about 80 members of the Munich Symphony Orchestra and 170 singers of the University Choir of Munich

If you think, this has something to do with opera, you’re wrong. After all, Wicki has to deal with a merciless time corset: The music has to match the movie exactly - preferably to the centisecond. The consequence: minimal freedom, maximal concentration.

The trick: Wicki has not just the score in front of him but a laptop as well. There he sees the movie – and more: This is everything he needs and what’s confusing the rest of us: colored stripes that move from the left side of the screen to the right, white flashing punches and figures. To quote the movie: One screen to rule them all.

There are almost no breathing pauses for the orchestra and the conductor (the choir has a bit less to do): the movie runs for about three hours, the music for about 2 hours and 40 minutes. “That means, you can barely relax. You’re permanently under high tension.” conductor Wicki illustrates. Of course, even if there’s no music you have to pay attention, otherwise you’d miss your cue.

Incidentally, Wicki even flew to NY to program the conducting aid and adjusted the Auricle to meet his wishes. “I’ve tidied it up, so I can focus on the essentials.”

The rehearsals were “uncompromising” Wicki says smilingly. On one day from 10am to 5pm and on an other from 10am to 5.45pm. Still, if you attend a rehearsal, you can sense it: Wicki’s cheerful, democratic nature appeals to choir and orchestra. “Fortunately, the times of the old, autocratic conductor’s stand stars are over.” Wicki says.

The Lord of the Rings is pretty much the most difficult piece of its kind – more difficult than conducting one of Chaplin’s silent movies, for instance. Wicki explains the difference: “Modern Times, City Lights – they have more consistent musical arcs, coherence. But this [LotR] is all about rhythm changes and tempo changes. For three hours.”

What makes this production really expensive is the backup: The movie is shown on the big screen and on Wicki’s laptop – to ensure maximum security in case one system fails. It would be fatal indeed if the music would stop right in the middle of the battle of Helm’s Deep, wouldn’t it? So: To battle!

Ludwig Wicki was born 1960 in the Canton of Lucerne and is a very versatile musician: He was a trombonist in the Lucerne Symphonic Orchestra in the ‘80s, directs a choir, and is a lecturer and musical director of the Hof Church in Lucerne. Ten years ago he founded his 21st Century Symphony Orchestra, which is specializing in film music. Last year he conducted the world premiere of The Fellowship of the Ring in Lucerne, the first part of the Rings saga, – and the following performance in Munich.

Into the Light

It has become almost a cliché, in the realm of serious choral music, to refer to the “Swedish Choral Miracle”-- the development, since World War II, of a phenomenally high-level choral culture, based in Sweden but spreading throughout the Scandinavian countries and east to Finland and the Baltic republics.

Two summers ago, the Oregon Bach Festival orchestra, chorus, and soloists presented the premier of Sven-David Sandström’s Messiah, a commission based on Handel’s work of the same name. Present and active throughout the Festival, Sandström attended rehearsals, tweaked the score, presented talks and participated in symposia. He is a cordial, engaging man, eager to talk about his craft and his background; we participants enjoyed his residency. At one point, in speaking of his compositional procedure, he mentioned, almost off-handedly, that, as a Swede, he had been privileged, throughout his career, to have at his immediate disposal the finest choirs in the world, who could sing anything he threw at them. I say off-handedly, because it has become almost a cliché, in the realm of serious choral music, to refer to the “Swedish Choral Miracle”-- the development, since World War II, of a phenomenally high-level choral culture, based in Sweden but spreading throughout the Scandinavian countries and east to Finland and the Baltic republics. Sandström’s Messiah proved to be very difficult for everyone involved; but the composer never apologized, never offered to rewrite anything to aid performance: he knew that, if we couldn’t handle the work, choirs back home in Europe could.

Many reasons come to mind for the existence of this pocket of choral excellence: the region’s relative isolation and strong drive toward various expressions of nationalism; historically high rates of literacy; the prevalence of good choral music in the Lutheran church; Sweden’s relatively wealthy, unscathed emergence from the war, and subsequent egalitarian distribution of that wealth; the phonetic structure, especially of the Nordic languages; an inspiring natural landscape; the seriousness and high level of personal discipline and community involvement amongst the populations. Something about this combination of elements, inspired by strong individuals such as conductor and teacher Eric Ericsson, inspired, and continues to inspire, singers, conductors, composers, to produce work of mind-bending competence and difficulty, and often of great beauty.

In general, Scandinavian and Baltic choral music has a neo-romantic tonal base, though it often ventures very far from this base. Generally (entirely, in Chorale’s program) it is performed a cappella, and consequently requires a narrow tonal focus from all singers, to accomplish intricate harmonic changes clearly. A “boyish” sound, however, is not desirable: singers are from time to time asked to sing with a fuller sound, and the sopranos and altos to utilize a characteristically “feminine” timbre. Mostly-- singers are to sing with great discipline, and to bury their own vocal quality in the cool, somewhat impersonal texture characteristic of the music. When not at its best, the sound—the entire approach—can become, frankly, boring: a perfect, bland surface, which becomes tiresome. At its best, though, this music, like all Northern art, contrasts light and dark, warm and cold, high and low, with a vocabulary which suggests much that is unsaid-- almost a musical representation of the chilly blond beauty of Alfred Hitchcock’s favorite actresses, implying far more than they at first seem; beauty and danger in at least equal parts.

This is our program, at least at this point, August 1:

Edvard Grieg; Fire Salmer, Opus 74

1. Hvad es du dog skjön

2. Guds Sön har gjort mig fri

3. Jesus Kristus er opfaren

4. I Himmelen

Nils Lindberg: Den signade dag

Bach/Nystedt/Sandström: Komm süsser Tod

Jan Sandström: Gloria

Otto Olsson: Jesu dulcis memoria

Knut Nystedt: Audi

Knut Nystedt: O crux

Einojuhani Rautavaara: from Vigilia

Katisma

Psalm

Herra Armahda

Arvo Pärt: Bogoroditse Djevo

Urmas Sisask: Benedictio

A challenging program for us, though all of it unimpeachably beautiful music. I’ll write more about it once our rehearsals commence (September 7) and I hear how it sounds. Concerts November 18 (Hyde Park Union Church) and November 19 (St. Vincent DePaul, in Lincoln Park).

Next: Lord of the Rings at Ravinia, August 18-19

Chicago Chorale joins forces with the Lakeside Singers, the Chicago Children’s Choir, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, under Ludwig Wicki's baton, to perform the soundtrack in a showing of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Rings at Ravinia Park

Thursday and Friday, August 18-19, Chicago Chorale will join forces with the Lakeside Singers, the Chicago Children’s Choir, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Ludwig Wicki, to perform the soundtrack in a showing of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Rings at Ravinia Park. I fully expect that the park, and the pavilion, will fill to capacity both nights.

Electronics being what they are, these days, it appears to be a matter of pressing a few keys, to eliminate the musical soundtrack, while leaving dialogue and all other elements of the soundscape intact, and replace it with live performance. Coordinating the live performance with the film, however, matching everything up frame by frame, is a daunting challenge. The conductor has presented this very program several times, with numerous orchestras and choruses; none of the rest of us have ever done it, however, and we will need to be on our toes at all times. The entire movie has only forty minutes of vocal music, but that vocal music occurs, here and there, in major scenes as well as in limited, eight-bar phrases, throughout the performance. The full score, which I am studying and which I will use in leading rehearsals, has all of the music for the entire film, and weighs about five pounds; the choral scores have only the voice parts, with no accompaniment and only minimal orchestral cueing. The singers must count bars for pages at a time, before suddenly entering , often at a forte, at the extremes of their vocal ranges, frequently at breakneck tempos. Meters constantly change, as do tempo markings; and the singers must perform in such languages as Orc and Elvish, which are written in the score in something similar to what a middle school student might use if he were asked to spell out street slang, rather than in IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet), which singers are trained to read. Adding insult to injury—the font seems intended to look like Elvish runes—very decorative, but not much good for speed reading!

Vocal demands are tremendous. In such scenes as the Mines of Moriah, the choir is divided into as many as twelve parts, with basses singing page after page of low D’s while the first sopranos hang out on high A’s and B’s, all at fortissimo levels.

I have been watching the film, and listening to a recording of the sound track, in preparation for our first rehearsal (we begin Monday evening, August 1, and meet nearly every day up to the performances). In the past, when I have watched the film, I have not paid much attention to the music; I have known it is there, and have appreciated the skill with which it augments the viewing experience, but I have left it in the background—which after all is where it belongs. Now that I am studying it, I realize, more with each exposure, how brilliantly it has been composed, and how masterfully it has been woven into the total fabric of the experience. I have heard that the composer, Howard Shore, spent three full years composing and preparing the music for the three films in the trilogy, and I am not in the least surprised-- in its way, his task has been fully as complicated and all-encompassing as Bach’s task in composing the St. Matthew Passion. This is magnificent stuff.

I don’t think I need to promote the performance-- people are very excited about it, and I just hope they are not turned away at the gates, after driving from all points in the Chicagoland area to attend the performances. Nonetheless, I urge you to look at your calendars for August 18-19; if you can come and hear it, I’m sure you will agree with me that this is a stunning accomplishment, for the orchestra, the choruses, and the conductor. And the movie isn’t bad, either.

Home again, home again, jiggety jig!

Chicago Chorale conceptualise l’amour du chant, propre aux véritables amateurs.

The Chicago Chorale, composée d’une soixantaine de voix, conceptualise l’amour du chant, propre aux véritables amateurs. Son repertoire, puisé dans les chants sacrés et classiques du XVIè siècle à nos jours, permet aux choristes, sous la direction de Bruce Tammen, de rechercher l’excellence musicale et ainsi ravir le public.-- Eglise du Vigan

Those French… it’s not what they say, exactly, but the way they say it. Ravir le public…

Chorale has recently returned from a 10-day trip through northern Spain and France, during which we sang five concerts in absolutely glorious venues, all the way from the above-referenced Eglise du Vigan, a Romanesque parish church in the valley of the Dordogne, near Rocamadour, to the monumental Madeleine, in Paris. Each church we sang in, large or small, was filled with appreciative listeners-- to look out on the crowd filling La Madeleine was thrilling and humbling, but not more so than to see St. Barthélémy in Cahors stuffed practically to it’s windows, or the capacity crowd at the Basilica de Santa Maria d’Igualada, north of Barcelona-- every audience was eager, engaged, responsive, grateful. At three of our venues—Alzonne, Cahors, and Le Vigan—we were hosted by local choirs, which sang for us, joined us for shared pieces, and feted us with wonderful receptions, featuring the wines of their particular locales. In preparation, we learned “Se Canto,” which seems to be the national anthem of the Occitan region of Spain and France, and our hosts greeted our singing of it with great enthusiasm.

Our tour agency, Music & Travel Tour Consultants Ltd., based in England, did a splendid job for us, balancing our desire to sing in the best possible venues, for the largest possible audiences, and our wish to see and experience a beautiful part of the world, with our budget constraints. Had the tour cost the individuals any more than it did, we would have lost singers, and been forced to travel and perform with a less than optimal ensemble—and it did not add up for us, to enjoy larger hotel rooms, but cheat ourselves musically. The company’s president, Matthew Grocutt, along with the choir’s tour committee, came up with just the right compromises, tweaked things in just the right directions, and provided us with the best experience available to us.

I have performed in Europe with several different organizations, some of them American, some not, and I am all too familiar with the “ugly American” stereotype, and with the manner in which Europeans brace themselves to deal with us. Indeed, we can be loud, insensitive, demanding, easily disappointed, hard to satisfy. The tours I took with the Gächinger Kantorei were a revelation to me, as I observed the modest and agreeable behavior of the German singers, compared to the behavior of the Americans with whom I sang in the Robert Shaw Choral Workshops, who constantly complained about French pillows and coffee, and required ketchup with their meals. Fortunately, Chorale behaved beautifully—the singers were flexible, adventurous, excited and pleased by almost everything, and demonstrated both gratitude and a sense of adventure every step of the way. Chorale is a classy group; its members tend to be more facile than average with languages, unabashedly interested in the things we were seeing and hearing, experienced and comfortable at dealing with strange or unexpected situations. Along the way, I sensed that the hotel and restaurant staffs relaxed some as they got to know us, and actually enjoyed our business; and I know that the groups which hosted us were happy they had made the effort, and saddened only that we could not stay longer, drink more, after the concerts.

Mostly, though, the tour was about music. We sang a program which challenged our audiences—but they warmed quickly to us over the course of an evening’s concert, and their enthusiasm by the end of the program was boundless. We worked hard to prepare this music; we arrived prepared, and we grew with each performance, adjusting to acoustics, to lighting, to the beauty of our surroundings, and to the constant proximity of one another. All of these variables play a huge role in a choral ensemble’s success, and Chorale responded wonderfully to them, becoming a tighter group with each outing. We return to Chicago with a higher standard for ourselves, and even more enthusiasm for the sort of work we do.

This tour was a great thing for Chicago Chorale. To all who helped, those who came along and those who supported from home, a huge thank you!

Chorale European Tour concert program

Here's what Chicago Chorale will sing on its concerts in Spain and France!

Here's what we'll be singing!

I.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594) Sicut cervus…Sitivit anima mea

Gunnar Ericksson (b.1931) Kristallen den fina

Trond Kverno (b. 1945) Ave maris stella

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) Os justi

II.

Einojuhani Rautavaara (b. 1928) Vigilia

1. Ehtoopalvelus

3. Katisma

4. Avuksihuutopsalmi

7. Ehtoohymni

10. Herra Armahda

14. Loppusiunaus

III.

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) Rejoice, O Virgin

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Salve Regina

Stephen Paulus (b. 1949) And Give Us Peace

IV.

Johann Nepumuk David (1885-1977) Deutsche Messe

Sanctus

Agnus Dei

Randall Thompson (1899-1984) Alleluia

Alice Parker and Robert Shaw, arr. American Folk Hymns

Wondrous Love

Hark, I hear the Harps Eternal

Alternate selections:

Javier Busto (b. 1949) Ave Maria

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Calme des nuits

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) Toast pour le nouvel an

We won't be able to sing all of the pieces at each concert-- though this is a short program (about an hour of music) we have been asked to shorten it even further for certain venues. We'll do our best along the way to sing as much as we can-- it is all wonderful music, representative of our first ten years of a cappella programming, suited to our forces and to the acoustics in which we will perform. Just looking over the list ups my anticipation for this project! We'll sing this program at our Saturday, June 4 concert at Hyde Park Union Church-- if you are in town, we hope you will come and hear it!

Ten Years of Growth and Change

Chicago Chorale happened because I was unemployed and needed something to do, and friends encouraged me to take the risk.