An Image That Fits The Music: A Guest Blog Post by Managing Director Megan Balderston

One of my unexpected “favorite” things about being Managing Director of Chicago Chorale is that of being the brand ambassador, which is a fancy way to say that I get to work closely with our graphic designer to pick the images around our concert and brochure artwork. Over the years this has turned into a labor of love for Artistic Director Bruce Tammen and me, who are often the final decision makers for our concert artwork.

I am certain we are not the easiest people to work with. For a recent concert, the direction I gave our intrepid graphic designer, Arlene Harting-Josue, was: “Can we come up with some abstract image that presents these concepts: something upwards and onwards. Something perhaps joyous, but seriously so. Not whimsical, not antique; but something fresh and modern and inviting.” Somehow Arlene can sift through this and give us some great ideas. And we know what we like when we see it.

One of my unexpected “favorite” things about being Managing Director of Chicago Chorale is that of being the brand ambassador, which is a fancy way to say that I get to work closely with our graphic designer to pick the images around our concert and brochure artwork. Over the years this has turned into a labor of love for Artistic Director Bruce Tammen and me, who are often the final decision makers for our concert artwork.

I am certain we are not the easiest people to work with. For a recent concert, the direction I gave our intrepid graphic designer, Arlene Harting-Josue, was: “Can we come up with some abstract image that presents these concepts: something upwards and onwards. Something perhaps joyous, but seriously so. Not whimsical, not antique; but something fresh and modern and inviting.” Somehow Arlene can sift through this and give us some great ideas. And we know what we like when we see it.

The imagery for this concert was, therefore, a surprise. The Mozart Requiem is so iconic a piece, and despite the sadness of its subject matter, is not entirely sad. It is enshrouded in mystery. By its very unfinished nature, one always wonders what would have been, had Mozart lived to truly complete it. (See Bruce’s blog post about the Robert Levin completion we are using.)

Still, I was a bit surprised how the concert artwork affected our choir members when we presented it to them. For Bruce and me, the photograph was hands down our favorite in the mood it conveyed, and we didn’t ask about it. But the choir came back with: “What is the story of this image?” and “This image: I find it beautiful but it disturbs me, at the same time.” They asked me to go back to the photographer, Javier de la Torre, and find the story behind the photograph. Here is what he says:

“This pier is located in a really old fishing village called Carrasqueira, in the Alentejo area, close to Lisbon, Portugal. The piers have traditionally been maintained by the fishermen, but this particular pier is abandoned and no maintenance is done, so, nowadays, it doesn’t exist.

This shot was taken in 2010, and 3 years later, in 2013, I returned to Carrasqueira, but the pier was almost destroyed. Last December a great storm finally destroyed it totally, so, this shot cannot be repeated anymore.”

Knowing the story makes me appreciate our instinctive choice of the photo even more. For my part, I felt that the visual representation of the unknown structure of the pier beneath the surface, as well as the beauty of the colors, made for a striking and memorable image. Like music performed live, the photographer captured a moment in time that will never again be replicated. And Bruce? He says, “The feel of the image looks to me like the sound of the Lacrimosa movement.”

Interesting, ephemeral, and beautiful: much like Mozart’s music and his legacy.

Palestrina: The "Savior of Music"?

Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

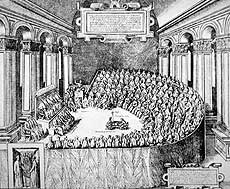

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the  increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

It seems unlikely that the Pope Marcellus Mass was composed with the intent of saving music, or even that Palestrina’s name, career, and music came up in the Council’s discussions. No documentation exists to support such a role for him. Most likely, he was a career church musician who was willing to make a few minor adjustments to fit certain requirements because it was the sensible thing to do. Nonetheless, beginning almost immediately in 1564, Palestrina became “the savior of music,” and remained so through the later twentieth century. The Roman Catholic Church presented his compositional style as a model for good church music, and generations of music students studied his works, particularly this mass, as an example of what they should understand and emulate. Giuseppe Verdi said of the composer, “He is the real king of sacred music, and the Eternal Father of Italian music.” In James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses (1934), Joyce's friend Frank Budgen quotes him as saying "that in writing this Mass, Palestrina saved music for the church." Palestrina’s magisterial image was set in stone.

Chorale is finding the Pope Marcellus Mass to be a very rewarding project. The music is lovely, soothing, uplifting; it flows so naturally and effortlessly, one would imagine its composition to have been easy for the composer. The more deeply we delve into it, however, the more we discover Palestrina’s craft and skill, and the genius of his contrapuntal writing. I discover, myself, a similarity to Mozart’s music: a gracious, pleasing, untroubled surface, a kind of abstract perfection: but so difficult to describe and define, once one is inside it. It demands extraordinary skill and grace in performance; and yields, on its own, incredible richness and satisfaction. Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.

Meet Chorale's B Minor Soloists

Chicago Chorale has a roster of outstanding soloists for its upcoming performance of the Mass in B Minor, March 26.

Chicago Chorale has a roster of outstanding soloists for its upcoming performance of the Mass in B Minor, March 26:

Michigan native Chelsea Shephard, soprano, recently gave an “exquisite” NYC recital debut, garnering praise for her “beautiful, lyric instrument” and “flawless legato” (Opera News). This season includes Ms. Shephard’s Carnegie Hall debut with Cecilia Chorus of New York for a World Premiere by Syrian composer Zaid Jabri and Brahms Requiem, joining Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster for Das Rheingold, and return engagements with the Madison Bach Musicians. Past season highlights include: Beth/Little Women, Calisto/La Calisto, Pamina/Die Zauberflöte, Susanna/Le nozze di Figaro, Lauretta/Gianni Schicchi, Lisa/The Land of Smiles, Emily Webb/Our Town, and Poppea/L’incoronazione di Poppea with companies such as Madison Opera, Opera Grand Rapids, Haymarket Opera Company, and Caramoor International Music Festival. Ms. Shephard’s accolades include: Education Grant/Metropolitan Opera National Council (2016), Finalist/Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ryan Opera Center (2015), First Place/Madison Early Music Festival Handel Aria Competition (2014), and Finalist/Jensen Foundation Competition in NYC (2014).

Michigan native Chelsea Shephard, soprano, recently gave an “exquisite” NYC recital debut, garnering praise for her “beautiful, lyric instrument” and “flawless legato” (Opera News). This season includes Ms. Shephard’s Carnegie Hall debut with Cecilia Chorus of New York for a World Premiere by Syrian composer Zaid Jabri and Brahms Requiem, joining Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster for Das Rheingold, and return engagements with the Madison Bach Musicians. Past season highlights include: Beth/Little Women, Calisto/La Calisto, Pamina/Die Zauberflöte, Susanna/Le nozze di Figaro, Lauretta/Gianni Schicchi, Lisa/The Land of Smiles, Emily Webb/Our Town, and Poppea/L’incoronazione di Poppea with companies such as Madison Opera, Opera Grand Rapids, Haymarket Opera Company, and Caramoor International Music Festival. Ms. Shephard’s accolades include: Education Grant/Metropolitan Opera National Council (2016), Finalist/Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ryan Opera Center (2015), First Place/Madison Early Music Festival Handel Aria Competition (2014), and Finalist/Jensen Foundation Competition in NYC (2014).

Chelsea holds degrees from DePaul University and Rice University.

Mezzo-soprano Angela Young Smucker has earned praise for her “luscious” voice (Chicago Tribune) and "powerful stage presence" (The Plain Dealer). Her performances in concert, stage, and chamber works have made her a highly versatile and sought-after artist. Highlights of the 2016-17 season include performances with Haymarket Opera Company, Bach Collegium San Diego, Chicago A Cappella, Seraphic Fire, and newly-founded Third Coast Baroque. Ms. Smucker has also been a featured soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Music of the Baroque, Oregon Bach Festival, Bella Voce, and Les Délices. Radio and television appearances include Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, WFMT’s Impromptu and Live from WFMT, and WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Mezzo-soprano Angela Young Smucker has earned praise for her “luscious” voice (Chicago Tribune) and "powerful stage presence" (The Plain Dealer). Her performances in concert, stage, and chamber works have made her a highly versatile and sought-after artist. Highlights of the 2016-17 season include performances with Haymarket Opera Company, Bach Collegium San Diego, Chicago A Cappella, Seraphic Fire, and newly-founded Third Coast Baroque. Ms. Smucker has also been a featured soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Music of the Baroque, Oregon Bach Festival, Bella Voce, and Les Délices. Radio and television appearances include Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, WFMT’s Impromptu and Live from WFMT, and WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Currently pursuing her doctoral studies at Northwestern University, Ms. Smucker holds degrees from the University of Minnesota and Valparaiso University – where she also served as instructor of voice for seven years. She is a NATS Intern Program alumna, former Virginia Best Adams Fellow (Carmel Bach Festival), and serves as Executive Director of Third Coast Baroque.

A "superb vocal soloist" (The Washington Post) possessing a "sweetly soaring tenor" (The Dallas Morning News) of "impressive clarity and color" (The New York Times), tenor Steven Soph performs throughout North America and Europe. Recent seasons' highlights include appearances with The Cleveland Orchestra in an all-Handel program led by Ton Koopman; the New World Symphony and Seraphic Fire in Reich's Desert Music; Symphony Orchestra Augusta in Bach's B minor Mass; San Diego's Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra in Mozart's "Orphanage" Mass and Mass in C minor; Voices of Ascension in Bach's Magnificat and St. Matthew Passion; the Master Chorale of South Florida in Mozart's Requiem and Haydn's Lord Nelson Mass; Colorado Bach Ensemble in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion; Texas Choral Consort in Haydn's Creation; and the Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra in Handel's Messiah.

A "superb vocal soloist" (The Washington Post) possessing a "sweetly soaring tenor" (The Dallas Morning News) of "impressive clarity and color" (The New York Times), tenor Steven Soph performs throughout North America and Europe. Recent seasons' highlights include appearances with The Cleveland Orchestra in an all-Handel program led by Ton Koopman; the New World Symphony and Seraphic Fire in Reich's Desert Music; Symphony Orchestra Augusta in Bach's B minor Mass; San Diego's Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra in Mozart's "Orphanage" Mass and Mass in C minor; Voices of Ascension in Bach's Magnificat and St. Matthew Passion; the Master Chorale of South Florida in Mozart's Requiem and Haydn's Lord Nelson Mass; Colorado Bach Ensemble in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion; Texas Choral Consort in Haydn's Creation; and the Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra in Handel's Messiah.

Described as an Evangelist “first-class across the board,” (Chicago Classical Review) Steven performed with the Chicago Chorale in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion, at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion and with the Concord Chorale in the St. John Passion.

Steven holds degrees from the University of North Texas and Yale School of Music, where he studied with renowned tenor James Taylor.

Ryan de Ryke (baritone) is an artist whose versatility and unique musical presence have made him increasingly in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. He has performed at many of the leading international music festivals including the Aldeburgh and Edinburgh Festivals in the UK and the summer festival at Aix-en-Provence in France garnering significant acclaim as both a recitalist and singing actor.

Ryan de Ryke (baritone) is an artist whose versatility and unique musical presence have made him increasingly in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. He has performed at many of the leading international music festivals including the Aldeburgh and Edinburgh Festivals in the UK and the summer festival at Aix-en-Provence in France garnering significant acclaim as both a recitalist and singing actor.

Ryan studied at the Peabody Conservatory with John Shirley Quirk, the Royal Academy of Music in London with Ian Partridge, and at the National Conservatory of Luxembourg with Georges Backes. His is also an alumnus of the Britten-Pears Institute in the UK and the Schubert Institute in Austria where he worked with great artists of the song world such as Elly Ameling, Wolfgang Holzmair, Julius Drake, Rudolf Jansen, and Helmut Deutsch.

Ryan can often be seen collaborating with Haymarket Opera Chicago where he performed title role in Telemann’s Pimpinone, voted one of Chicago’s top 5 performances of 2013, and last season played the role of Sancho Panza in Don Quichotte.

My Third Time Around

How will I experience my fourth B Minor Mass performance? I don’t know, but I hope I’m lucky enough to find out.

Guest Blog by Dan Bertsche, who has sung tenor with Chicago Chorale since 2003, and currently serves as Secretary on Chicago Chorale’s Board of Directors.

Guest Blog by Dan Bertsche, who has sung tenor with Chicago Chorale since 2003, and currently serves as Secretary on Chicago Chorale’s Board of Directors.

I remember approaching my first Bach B Minor Mass, in 2006, something like Sir Edmund Hillary must have approached his ascent of Mount Everest. This work is so difficult and monumental, and the only path I saw to a successful performance was through hard work, by developing lung capacity, stamina, and endurance—and by staying hydrated. Rehearsals were exhilarating, but at the same time fatiguing. After that first performance, the profound satisfaction I felt was coupled with equally profound exhaustion—both physical and vocal. “I came, I sang, I conquered. Now I want to sleep.”

My second B Minor Mass—six years ago—felt quite different. My familiarity with the score, coupled with the fact that everything was pitched at a=415 (a half-step down), allowed more space for appreciating what makes this work so very great in the first place. This was no longer a forced march to the mountaintop; but a walk through a garden of wonders. I recall marveling at the complexity and perfection of the Kyrie I; admiring the skill with which the cantus firmus emerges from the secondary material in Confiteor (still my favorite movement of the entire work); and being astounded by how there could be so many 16th notes in so many voices and instruments in the Cum Sancto Spiritu, and that the movement could still come across with such clarity and coherence. During my second B Minor Mass, I learned to appreciate Bach as “master composer,” rather than as “master obstacle-course builder.”

This year, some of my reverence for Bach’s compositional skill has been replaced by more general gratitude for this monumental work. Had Bach not bothered to compose it, or had it been lost to history, right now Chicago Chorale would frankly be preparing to perform a lesser piece. But because of this gift to posterity, fifty-five ordinary people are experiencing the magic that happens when engaging this extraordinary work. And as we strive to bring out the very best in the B Minor Mass, the B Minor Mass is bringing out the very best in us. Our collective vocal production is more healthy and vigorous; we are listening better within and across sections; we are sitting up a bit straighter; and we are more honest with ourselves about which spots need individual attention. On some level, Chorale members know that a great performance of a mediocre work still yields a mediocre result. So we are grateful that Bach has given us a masterpiece with a nearly unlimited performance “upside potential,” and we are pulling together to get as close to that ceiling as possible.

This time around, I am also struck by how much fun rehearsals are, by how much I look forward to them, and by the fact that I leave each rehearsal more energized than when I arrive.

How will I experience my fourth B Minor Mass performance? I don’t know, but I hope I’m lucky enough to find out.

Chorale's Choices

No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

I have written largely about the historical/musicological aspects of presenting Bach’s Mass in B Minor, over the past weeks. Such a focus is inevitable: the score is enormous, complex, surrounded and influenced by competing traditions; a conductor is forced to make decisions about every page, and to coordinate these many decisions in order to come up with a coherent whole. No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

In the performance history of the work, enormous choruses, numbering in the hundreds, have sung, and continue to sing, the Mass in B Minor, though the general trend has been toward smaller forces– on occasion, just one singer per part. Chorale is fifty-six singers for this concert-- by no means a symphony chorus, but larger than the professional early music ensembles which present the most cutting edge versions of the work. We could have chosen to bypass the work altogether, in acknowledgment of historical correctness– but then we would be deprived of the glorious experience of learning and performing the work, and our audience would be deprived of the opportunity to hear it. So we choose to sing it, and to devote tremendous effort toward lightening our sound and articulation, while making the most of our full sound where it is needed and welcome.

I have written largely about the historical/musicological aspects of presenting Bach’s Mass in B Minor, over the past weeks. Such a focus is inevitable: the score is enormous, complex, surrounded and influenced by competing traditions; a conductor is forced to make decisions about every page, and to coordinate these many decisions in order to come up with a coherent whole. No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

In the performance history of the work, enormous choruses, numbering in the hundreds, have sung, and continue to sing, the Mass in B Minor, though the general trend has been toward smaller forces– on occasion, just one singer per part. Chorale is fifty-six singers for this concert-- by no means a symphony chorus, but larger than the professional early music ensembles which present the most cutting edge versions of the work. We could have chosen to bypass the work altogether, in acknowledgment of historical correctness– but then we would be deprived of the glorious experience of learning and performing the work, and our audience would be deprived of the opportunity to hear it. So we choose to sing it, and to devote tremendous effort toward lightening our sound and articulation, while making the most of our full sound where it is needed and welcome.

Frequently, even when larger groups sing it, a smaller group, termed concertists, will introduce many of the movements, will sing particularly exposed passages as solos, will even sing the more intimate movements entirely on their own. Sometimes, these concertists will be members of the choir; alternatively, they may be the soloists who also sing the aria and duet movements. This trend toward ripienist/concertist texture is supported by the scholarly literature. Chorale chooses to forego the ripienist/concertist procedure. It could have been interesting and appropriate for our forces, but our singers want to experience all of the music, each note, as an amateur event—an act of love. As Robert Shaw said—music, like sex, is too good to be left to the professionals. Again, this forces us to be more careful in our control of texture and dynamics than we would be if those issues were resolved through controlling the size of the forces.

Chorale chooses to sing the Latin text with a German pronunciation. Most ensembles use the more common Italianate pronunciation, and have good results; and recent research indicates that the German pronunciation Chorale uses, based on modern German, is not necessarily the pronunciation Bach used or intended. So we can’t defend our choice on a secure, scholarly basis. But our choice does suggest the music’s German background. And I agree with Helmuth Rilling’s contention that German consonants articulate more clearly than Italian, while German vowels narrow and clarify the vocal line, even for an entire section of singers, lending greater definition to Bach’s remarkably complex counterpoint. This is particularly necessary with a group of our size: clarity of pitch and line is far more important, in this music, than the beautiful, Italianate production of individual voices in the ensemble, which can actually work against an accurate presentation of Bach’s musical ideas.

We choose to present the Mass at Rockefeller Chapel, on the campus of The University of Chicago, because the building’s size and grandeur reflect Bach’s music more accurately than other spaces available to us. The Hyde Park community, which surrounds the Chapel, represents, in a purer form than other Chicago neighborhoods, the combination of scholarship, idealism, and high culture which can support concerts like this. A high percentage of Chorale’s regular audience are Hyde Park residents, and they often express appreciation for the level of Chorale’s striving and seriousness of intent. And from a purely monetary point of view, Rockefeller Chapel seats a sufficient number of listeners that, if we sell tickets effectively, we can cover a significant proportion of our production costs (which are mind-boggling) with door receipts.

We choose to present the Mass at Rockefeller Chapel, on the campus of The University of Chicago, because the building’s size and grandeur reflect Bach’s music more accurately than other spaces available to us. The Hyde Park community, which surrounds the Chapel, represents, in a purer form than other Chicago neighborhoods, the combination of scholarship, idealism, and high culture which can support concerts like this. A high percentage of Chorale’s regular audience are Hyde Park residents, and they often express appreciation for the level of Chorale’s striving and seriousness of intent. And from a purely monetary point of view, Rockefeller Chapel seats a sufficient number of listeners that, if we sell tickets effectively, we can cover a significant proportion of our production costs (which are mind-boggling) with door receipts.

Our concert is in one month. Sunday, March 26, 3 p.m.

We have rehearsed, and I have written about the experience, since the middle of December. The writing has focused my study, my listening, my thinking about the work; it has been a significant and helpful discipline for me. I hope you will come to our performance; and I hope you will spread the word, and bring your friends. I’m a believer; I am convinced that Bach’s Mass in B minor truly is “the greatest artwork of all times and all people,” and I’d like to show you why.

Composing the Mass in B Minor

Bach effectively spent his entire career composing Mass in B Minor— it consists of complete movements, and fragments, from throughout his compositional life, recomposed, reworded, reconfigured, stitched together with newly composed music.

Bach effectively spent his entire career composing Mass in B Minor— it consists of complete movements, and fragments, from throughout his compositional life, recomposed, reworded, reconfigured, stitched together with newly composed music — Bach scholar Christoph Wolff calls the Mass a “specimen book,” a collection of examples of genres and techniques which covers not only Bach’s personal history, but the history of Western music. In the process of compiling this music into a single great work, at the end of his life, Bach seems intent on summing up that history and presenting his summation to his successors. The Sanctus was first performed in 1724; movement 4 of the Credo, Et incarnatus est, thought to be the last music he composed, dictated to an assistant because Bach himself was blind, was completed in 1750. The remaining music reflects Bach’s experience during the intervening 26 years. Plagiarism and parody were not a dirty words in Bach’s time. Bach, and his colleagues, had immense responsibilities in the preparation and performance of music for the theater, the court, the church– and their success depended on getting it all done, rather than on satisfying a theoretical mandate that they be original. They were free, even expected, to build upon the successes of others, to copy and share one another’s scores, to use procedures and formulas, melodies and bass lines, that had worked well for other composers, and alter them to suit their own tastes and circumstances, even to change their own products and procedures over time as needs and tastes changed. Music was a living, volatile consumer product, constantly evolving to meet demand. Creativity reflected one’s ability to arrange the materials at hand, as well as to invent new materials. Bach borrowed freely and happily from other composers, as well as from himself, both because this enriched his product, and because it allowed him to keep up with his workload. It is inconceivable that Bach could have accomplished all he did in his lifetime, were he under pressure to stay away from the intellectual property of others.

An extraordinary amount of Bach scholarship over the past century has focused on sleuthing out the sources behind Bach’s music, and in preparing new and better editions of his music, based on this detective work. And while the scholars involved in this work frequently disagree with one another, as a group they persistently push the envelope, and contribute to our knowledge of the composer and his methods. Between them, these researchers have determined that very little of what is now called Mass in B Minor was freshly composed for the work– perhaps as few as four or five movements. Bach selected music for the remaining movements from cantatas which he had composed throughout his career. Scholars agree that he seems to have chosen what he thought was his best work, music which would suit the character of the Mass, and would reflect accurately the new, Latin texts. He transposed some movements to new keys, in keeping with the overall key structure of the new work; he adapted phrase structure to fit the alternate texts; he eliminated instrumental introductions and interludes, to move the dramatic action forward more efficiently; and he composed new movements, and sections of movements, where he needed them to complete the work.

Though the Ordinary of the Roman Catholic Mass consists of only five movements—Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus/Benedictus/Osanna, and Agnus Dei—Bach divides the text and music of his Mass in B Minor into twenty-three separate movements. With the exception of the Gratias/Dona nobis movements, and the repeat of the Osanna, each movement has different music.

Let’s consider movements 3-6 of the Credo portion: Et in unum Dominum, Et incarnatus est, Crucifixus, and Et resurrexit. Scholars agree, based on internal evidence, that Bach adapted the duet Et in unum from an earlier composition, though that earlier work is lost. The close imitation between the two voices is ideally suited to a love duet, probably from a secular work, and adapts easily to a text which expresses the consubstantiality of the Father and the Son. In his original version of the Mass, Bach set the entire text of movements three and four within this one movement. It was only in the final months of his life (determined, again, on the basis of internal evidence) that he decided he needed a separate movement to set the words “And was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man.” So he kept the music for movement 3 intact, had the soloists repeat earlier words, and composed a completely new movement — one of the few freshly-composed movements in the Mass, and one of Bach’s final compositional efforts. In so doing, he created a numerical symmetry which the Credo had previously lacked, placing the Crucifixus exactly at the center of this discrete section, as well as at the center of all of the Mass movements which lie between the identical music of the Gratias and the Dona nobis movements. It is an amazing engineering feat, adding internal structure for the connoisseur and first time listener alike.

Bach adapted the Crucifixus movement from his cantata BWV 12, where it has the words Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, lamentation,worry, apprehension). Bach scholar John Butt hypothesizes that Bach could have adapted even this early cantata movement (1714) from a similar movement by Vivaldi (Piango, gemo, sospiro e peno), but goes on to say that such laments were standard literary forms, and that, together with its descending bass line, is such a standard form that it would be stretching things to suggest that Bach did anything other than compose his own version of a common form. More interesting are the final four bars of the Crucifixus; Bach added these to the music he borrowed from himself, and with them modulates to G Major (setting up the D Major of the following Et resurrexit) and brings the choral forces down to the lowest pitches they sing in the entire Mass, representing the lowering of Christ’s body into the sepulchre. The following movement, Et resurrexit, explodes out of this depth with no instrumental introduction—voices and instruments enter with a complete change of affect, in a fanfare-like, rising triad. Scholars assume that this movement, as well, is adapted from an earlier, secular cantata—possibly the lost birthday cantata for August I, BWV Anh. 9. In adapting it, Bach dropped the opening instrumental introduction, which would have slowed down the drama of Easter morning, but included other instrumental interludes, which have a euphoric, dance-like character and seem to suggest heaven and earth rejoicing.

Bach adapted the Crucifixus movement from his cantata BWV 12, where it has the words Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, lamentation,worry, apprehension). Bach scholar John Butt hypothesizes that Bach could have adapted even this early cantata movement (1714) from a similar movement by Vivaldi (Piango, gemo, sospiro e peno), but goes on to say that such laments were standard literary forms, and that, together with its descending bass line, is such a standard form that it would be stretching things to suggest that Bach did anything other than compose his own version of a common form. More interesting are the final four bars of the Crucifixus; Bach added these to the music he borrowed from himself, and with them modulates to G Major (setting up the D Major of the following Et resurrexit) and brings the choral forces down to the lowest pitches they sing in the entire Mass, representing the lowering of Christ’s body into the sepulchre. The following movement, Et resurrexit, explodes out of this depth with no instrumental introduction—voices and instruments enter with a complete change of affect, in a fanfare-like, rising triad. Scholars assume that this movement, as well, is adapted from an earlier, secular cantata—possibly the lost birthday cantata for August I, BWV Anh. 9. In adapting it, Bach dropped the opening instrumental introduction, which would have slowed down the drama of Easter morning, but included other instrumental interludes, which have a euphoric, dance-like character and seem to suggest heaven and earth rejoicing.

In his handbook for the study of the Mass in B Minor, John Butt recounts the experience of early Bach scholar Julius Rietz, who wrote the first published study of the sources of the Mass in 1857: “Reitz shows himself to have been a meticulous scholar, who even made enquiries into the fate of Bach’s first set of parts of the Sanctus, copied in 1724 and loaned to Graf Sporck. The inheritors of the estate informed Rietz that many manuscripts had been given to the gardeners to wrap around trees. One can barely dare to envisage what similar fates befell other manuscripts from Bach’s circle.” I expect Bach would not have been surprised by this; the archives and libraries of our modern world would probably astound him. Christoff Wolff suggests that one of the principle motivations behind Bach’s compilation of the Mass was his assumption that the thousands of pages of his cantata cycles would not be preserved—that they were too specific to their own time, location, and purpose to be of any use once he was gone, and that the only way he could preserve the best of his work was to use it for a Latin Mass, which would have a better chance of being saved and recognized in the future. My years of participation in the Oregon Bach Festival have given me the opportunity to sing and study many of Bach’s surviving cantatas, but I am lucky to have had this experience—most performers know only a handful of them, and most listeners don’t know them at all. So from our viewpoint, Bach had it right—his Mass enables us to know not only what he was able to preserve, but also the dimensions of our loss.

I read somewhere that Bach shows us what it means to be God, Mozart shows us what it means to be human, and Beethoven shows us what it means to be Beethoven. I agree with the Bach part, at least. Beyond the notes, the rhythms, the historically informed performance practices, one experiences his works as living beings, as manifestations of God in the world. They demonstrate that we humans are better than we think we are, better than much of what we see around us, and convince me that it is always worth it to keep moving ahead, not just out of habit, but because we, like Bach, are capable of holy things.

Chicago Chorale and Historically Informed Performance Practice

Bach was not only a genius; he was a practical, practicing musician. Knowing what he heard, and how he did it, can only improve our performances of his work.

I began attending Oberlin Conservatory’s Baroque Performance Institute in 1978, and continued attending for about eight summer sessions following that. I first learned of the Institute through Ken Slowik, a Chicago cellist and early music specialist, who suggested that my vocal characteristics and musicological curiosity might make me a good candidate for BPI-- especially since Baroque expert Max Van Egmond was joining the faculty that summer. I listened to some of Max’s recordings, recognized a kindred spirit, and decided to take the plunge. The experience was revelatory for me: prior to that, I had never even heard of Baroque pitch, of gut strings, of wooden traverso flutes, of viols, of inégale rhythm. An entirely new world opened for my consideration, and I ate it up, eagerly and hungrily. Max was an ideal teacher and mentor for me, and I sang as often as I could, in lessons, master cases, and concerts; and I observed instrumentalists when I was not singing. BPI was all about performance; scholars and theorists attended, lectured, and added their insights, but the focus was on performing, day and night. I had never loved any musical immersion so much, in my life.

And then, when BPI was over, I would return to my job, conducting choirs and teaching voice, first at Luther College, later at The University of Chicago—and I would have a hard time integrating my BPI experience with my actual day job. One year Ken invited me to sing with the Smithsonian Chamber Players (he was by this time their music director) in Washington, for a performance of Charpentier’s Les Arts Florissants , complete with dance, masks, authentic instruments from the Smithsonian collection—we were so authentic, we even lighted the performance with candles in metal reflectors. The other singers were recognized professionals in the early music field, who did this sort of thing on a regular basis; for me, it was a brief interlude, a vacation, from my teaching. The contrast struck me forcibly, and I withdrew from involvement in early music performance from that point on—I could not see any further value in doing it part way, and I did not want to give up my actual professional life. I enjoyed my students, my choirs, and could not see how this hobby of mine was contributing anything to the health of my program.

I began attending Oberlin Conservatory’s Baroque Performance Institute in 1978, and continued attending for about eight summer sessions following that. I first learned of the Institute through Ken Slowik, a Chicago cellist and early music specialist, who suggested that my vocal characteristics and musicological curiosity might make me a good candidate for BPI-- especially since Baroque expert Max Van Egmond was joining the faculty that summer. I listened to some of Max’s recordings, recognized a kindred spirit, and decided to take the plunge. The experience was revelatory for me: prior to that, I had never even heard of Baroque pitch, of gut strings, of wooden traverso flutes, of viols, of inégale rhythm. An entirely new world opened for my consideration, and I ate it up, eagerly and hungrily. Max was an ideal teacher and mentor for me, and I sang as often as I could, in lessons, master cases, and concerts; and I observed instrumentalists when I was not singing. BPI was all about performance; scholars and theorists attended, lectured, and added their insights, but the focus was on performing, day and night. I had never loved any musical immersion so much, in my life.

And then, when BPI was over, I would return to my job, conducting choirs and teaching voice, first at Luther College, later at The University of Chicago—and I would have a hard time integrating my BPI experience with my actual day job. One year Ken invited me to sing with the Smithsonian Chamber Players (he was by this time their music director) in Washington, for a performance of Charpentier’s Les Arts Florissants , complete with dance, masks, authentic instruments from the Smithsonian collection—we were so authentic, we even lighted the performance with candles in metal reflectors. The other singers were recognized professionals in the early music field, who did this sort of thing on a regular basis; for me, it was a brief interlude, a vacation, from my teaching. The contrast struck me forcibly, and I withdrew from involvement in early music performance from that point on—I could not see any further value in doing it part way, and I did not want to give up my actual professional life. I enjoyed my students, my choirs, and could not see how this hobby of mine was contributing anything to the health of my program.

My succeeding summers were spent, first, at the Nice Conservatory, singing art songs with Gérard Souzay and Dalton Baldwin; then several years with the Robert Shaw Festival Singers; and, finally, ten summers with Helmuth Rilling at the Oregon Bach Festival. All of it was good and worthwhile and stimulating, and contributed to my professional competence.

What goes around, comes around. The bug that bit me back at Oberlin did not die; it just invaded the rest of my music making. Working with both Mr. Shaw and Mr. Rilling, I found myself observing and questioning what they were doing, comparing it to my BPI experience, wondering how it was related, how it could be different, and how I could do things differently, myself, with my own ensembles. During Chorale’s second season, already, we presented the first half of J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, and we have been programming major Baroque works, primarily Bach’s, ever since. With each successive concert, I introduce more HIPP elements, try more techniques I remember from my Oberlin experiences, require a more “baroque” sound from both the players and the singers, hire more appropriate soloists. Obviously, we do not do museum-quality reproductions of performances that Bach himself led or heard: we do not have his performance space, his highly trained 16-year old prepubescent boys, or his audience. We prepare performances for the buildings we have, with the singers we have, and with our contemporary audiences in mind. But, as I discovered at Oberlin, having a good idea of Bach’s circumstances, knowing what was physically and musically possible for him, and being aware of his goals—his desire to clarify, to instruct, to be understood, to get his message across—has really helped me to sort out what is good and necessary in what I learned at BPI. Bach was not only a genius; he was a practical, practicing musician. Knowing what he heard, and how he did it, can only improve our performances of his work.

Black with Notes

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move.

Chorale is seven rehearsals into its preparation for our March 26 performance of Bach’s Mass in B Minor. I am grateful for so extended a rehearsal period-- every singer in the group benefits from repeated exposure to this complex, difficult music.

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move, aiming for the next harmonic arrival point, then taking off again once it is reached. The overall effect is—page after page of notes, thousands of them; how does one organize them? Where does one begin in breaking them down into comprehensible groupings, in assigning emphasis, ebb and flow, in such a way that they all make sense, all get heard, all matter and contribute positively, without just canceling one another out in a cloud of sound?

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move, aiming for the next harmonic arrival point, then taking off again once it is reached. The overall effect is—page after page of notes, thousands of them; how does one organize them? Where does one begin in breaking them down into comprehensible groupings, in assigning emphasis, ebb and flow, in such a way that they all make sense, all get heard, all matter and contribute positively, without just canceling one another out in a cloud of sound?

The first movement of the Mass in B Minor, Kyrie I, immediately plunges us into this “Bach problem.” After a 4-bar, homophonic introduction, the movement unfolds in thirteen independent musical lines, in addition to the continuo line. Singers aren’t accustomed to thinking much about instrumental lines– we see five vocal lines, and figure our job is to make sense of those; it surprises us to learn that the instruments do more than just accompany us, and have their own, independent lines, weaving in and out of what we are doing. Fundamentally, there is no hierarchy; each line contributes equally to Bach’s structure and texture. We need to find hierarchy within our own lines—periods of higher energy, balanced with periods of relaxation; figures which require pointed, staccato or marcato emphasis, and figures with require legato; passages of a more soloistic character, and passages of background accompaniment. If we don’t find hierarchy within our own parts, relative to the rest of what is going on, we end up sound like a beehive on a warm day, lots and lots of buzzing.

A Chorale member commented on a performance of the Mass with his college choir, that “we just tried to sing the notes; we never did anything with all this articulation stuff.” I know what he is talking about: even with a high percentage of singers who have previously performed the work, Chorale struggles to find pitches and rhythms; vocal quality, articulation, phrasing, would be complete non-starters, were I not constantly stopping to point them out, dictate them, and work on them. The Bärenreiter piano-vocal scores we sing from are “clean”—they include very little that Bach himself did not notate in his own scores, and Bach did not customarily notate much in the vocal lines. The instrumental lines are fairly marked up, following Bach’s own score and parts, and many of these marks have been transferred to the piano reduction in the singers’ scores—but singers are not prone to look down to the piano line: following their own line is about all they accomplish at this point. So we transfer the markings to the vocal parts in rehearsal, and then rehearse characteristic phrase articulations, ornaments, etc. Taken by themselves, these articulations can seem pretty mechanical and not awfully graceful; they have to be performed with understanding and within the context of the vocal line, and this is extremely difficult– Bach demands a great deal. I urge the singers to listen to the 2015 Gardiner recording, as an example of the sort of articulation and expressiveness we are after; but it takes a great deal of familiarity for them to internalize these gestures and allow them to mean something, rather than just perform them mechanically. The individual lines have to flow; they have to alter in emphasis and adjust to the volume, the surrounding parts, the intensity of individual passages; and this requires far more than mechanical competence and repetition.

I ran across the following passage by Martin Luther yesterday: “This life therefore is not righteousness, but growth in righteousness, not health, but healing, not being but becoming, not rest but exercise. We are not yet what we shall be, but we are growing toward it, the process is not yet finished, but it is going on, this is not the end, but it is the road. All does not yet gleam in glory, but all is being purified.” Very much the same thing can be said about learning to sing this music-- our rehearsal period is a kind of pilgrimage, a process. With every preparation Chorale does of this “greatest of all works,” we draw closer to the essential truth of this great composer and his overwhelming accomplishment. The Mass in B Minor is not only the best we humans can come up with, but it is transcendingly good, and we are a part of this transcendent goodness; there is more to us, more to hope for and plan for and celebrate, than the brutality, the violence, the hatred, which we daily confront in one another. A human being, one of us, composed this monumental and life-transforming work; just knowing that, should make us better people.

Back to Bach

This is Chorale’s third preparation of the Mass in B Minor, usually considered the greatest composition for chorus and orchestra in the Western canon; it is rivaled only by Bach’s other greatest choral/orchestral work, the Matthew Passion, which Chorale presented two years ago.

Chorale is four weeks into rehearsal for our March 26 performance of J.S. Bach’s Mass in B Minor. This is Chorale’s third preparation of this work, usually considered the greatest composition for chorus and orchestra in the Western canon; it is rivaled only by Bach’s other greatest choral/orchestral work, the Matthew Passion, which Chorale presented two years ago. The Mass edges out the Passion only because the Mass is truly a choral work, the choral movements greatly outnumbering, even overshadowing, the solo movements; each stands alone as a supreme example of the choral art, and the whole is an overwhelming tour de force for the choir. The Passion, which is a continuous narrative dialogue, gives far more weight to the soloists, leaving the choir to sing significantly less than it does in the Mass. Understandably, ambitious choirs tend to prefer the Mass… and this preference finds expression in the good natured euphoria greeting our opening rehearsals. The majority of Chorale’s singers have sung the Mass at least once, and are familiar both with the notes and with the overwhelming majesty of the work; and they carry the neophytes with them. We can already hear what the finished product will sound like—which is a far different experience than that enjoyed by a choir reading this mind-boggling difficult score for the first time.

Our preparation is greatly influenced by the historically informed performance practice (HIPP) movement of the second half of the twentieth century. Voices, and instruments, are tuned to a=415, approximately one half step lower than modern pitch; and our orchestra will play on copies of period instruments—gut strings, wooden flutes, natural horns and trumpets, etc-- which have a very different characteristic sound than modern instruments: they are far softer in volume and quality, they play with less vibrato, and they rely more on articulation than on unbroken legato sound. Our sopranos and altos are women, rather than the boys and counter tenors Bach would have employed, but they sing with a narrower, straighter sound than modern singers would usually employ. And we work hard to sing with the kind of non-legato articulation we will hear from our instrumentalists, the kind of articulation that “reads” well when presenting music as complex and polyphonic as this, in a resonant space.

Chorale is four weeks into rehearsal for our March 26 performance of J.S. Bach’s Mass in B Minor. This is Chorale’s third preparation of this work, usually considered the greatest composition for chorus and orchestra in the Western canon; it is rivaled only by Bach’s other greatest choral/orchestral work, the Matthew Passion, which Chorale presented two years ago. The Mass edges out the Passion only because the Mass is truly a choral work, the choral movements greatly outnumbering, even overshadowing, the solo movements; each stands alone as a supreme example of the choral art, and the whole is an overwhelming tour de force for the choir. The Passion, which is a continuous narrative dialogue, gives far more weight to the soloists, leaving the choir to sing significantly less than it does in the Mass. Understandably, ambitious choirs tend to prefer the Mass… and this preference finds expression in the good natured euphoria greeting our opening rehearsals. The majority of Chorale’s singers have sung the Mass at least once, and are familiar both with the notes and with the overwhelming majesty of the work; and they carry the neophytes with them. We can already hear what the finished product will sound like—which is a far different experience than that enjoyed by a choir reading this mind-boggling difficult score for the first time.

Our preparation is greatly influenced by the historically informed performance practice (HIPP) movement of the second half of the twentieth century. Voices, and instruments, are tuned to a=415, approximately one half step lower than modern pitch; and our orchestra will play on copies of period instruments—gut strings, wooden flutes, natural horns and trumpets, etc-- which have a very different characteristic sound than modern instruments: they are far softer in volume and quality, they play with less vibrato, and they rely more on articulation than on unbroken legato sound. Our sopranos and altos are women, rather than the boys and counter tenors Bach would have employed, but they sing with a narrower, straighter sound than modern singers would usually employ. And we work hard to sing with the kind of non-legato articulation we will hear from our instrumentalists, the kind of articulation that “reads” well when presenting music as complex and polyphonic as this, in a resonant space.

In some respects, we are a thoroughly modern choir: we are 60 singers, rather than the 8-24 some scholars think Bach had in mind; we perform in a building which, though superficially resembling a “period” building, actually has modern, diffuse acoustics, and requires non-period forces to be adequately filled with sound; and we are presenting a “mass” as a concert, rather than in a liturgical context, with appropriate, necessary breaks during which the rest of the liturgy would occur. It is important to realize that this work was never performed, in its entirety, during Bach’s lifetime—neither as a concert, nor in a service. The former was just not the way music was presented, back then; and the work is far too large, and too long, for the latter. In fact, it isn’t at all clear Bach even intended that his mass be performed in its entirety; the work seems, rather, to be an encyclopedia of his career, of the music he composed throughout his lifetime (most of the movements are reworkings of earlier pieces of his), and of the styles and procedures available to a composer in his time, from the early stile antico to the operatic, style galant popular at the time of his death (1750). Perhaps, approaching old age and conscious of his place in music history, Bach intended to leave a record of himself and his work, an autobiography of sorts, and did it through compiling this great score.

Whatever Bach intended, it is an unqualified thrill for me, and for Chorale, to prepare this immense work of art once again. Our singers will never forget the experience; and their understanding of the power of music will be changed forever. The Mass in B Minor defines choral music, and defines choral singing.

Left Behind

The name grew on us, because it expressed the peculiar and tragic circumstances surrounding the music we had decided to program.

We named our upcoming concert “Left Behind” on a whim, last summer—we needed at least a placeholder, as we prepared promotional materials, and no other title presented itself. The name grew on us, however-- because it expressed, more clearly than anything else we came up with, the peculiar and tragic circumstances surrounding the music we had decided to program. I spent a good portion of my summer reading, and rereading, War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910). I was struck forcibly by Tolstoy’s grand, romantic, nationalistic vision-- his portrait of what he regarded as the true Russia, shining through the accretions of other, assumed, foreign cultural influences. His was a very important voice, in the immense surge of Russian nationalism which overwhelmed the country, politically and artistically, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—a surge so complicated, so contradictory, so inevitable, culminating in the Bolshevik Revolution which began in 1917. The Russian Orthodox Church was, at first, a major part of this surge—resulting in a fundamental rebirth and revitalization of the chants and other musical material from the historic past, and a purging of Western European musical influences which had crept in, along with other foreign influences, during the preceding several hundred years. It was a heady time for the composers and performers of church music, mostly centered in Moscow and constituting a group now known of as the New Russian Choral School—they produced a virtual explosion of new choral compositions, based on old models but with modern vigor and excitement, and fostered a vital, thrilling approach to choral performance, appropriate to these compositions.

The best-known name to emerge at this time, to us Americans, is Sergei Rachmaninoff, who composed two major choral cycles for the Orthodox church; but he was by no means alone. Other names include Pavel Chesnokov, Alexandre Grechaninov, and Nicolai Golovanov, who, along with a host of others, produced an immense body of repertoire over a very short period of time, about fifteen years, until they were cut short by the revolution, in 1917. The Orthodox church was ultimately closed down by the officially atheistic state, and with it, church music. Many of these composers left Russia while they could, but were unable to continue composing church music outside of their familiar context; others remained in Russia, but turned their skills toward composing instrumental music, or secular, nationalistic music for the state. Copies of their church music slowly became available in the West, at first in English translation, but more and more commonly, now, in the original Church Slavonic; the entire repertoire has become an important part of the world-wide canon of choral concert music. Very little of this music, however, was composed after 1917; its context had disappeared, as surely as the context for Bach’s cantatas has disappeared, and the music exists today as art music. That particular mode of composition, as a living expression of worship, was choked off, and left behind, in 1917.

A particularly poignant tragedy took place in the musical life of Maximilian Steinberg, a contemporary of the composers named above, who lived and worked in St. Petersburg, rather than in Moscow. Inspired by hearing a performance of Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil, he determined that he, too, would contribute to this repertoire, and he set to work composing a similar cycle, Passion Week, based upon historic chants and models. He continued working on it through the early years of the revolution, completing it finally in 1923. The anti-church stance of the revolutionaries had not started out as absolute, and Steinberg had hoped that his composition would be performed, at least as a concert piece; but by the time he had finished it, the work was condemned by the authorities, and the composer never heard it performed. More profoundly than for his Moscow colleagues, Steinberg’s work was left behind. He managed to get a copy of it to Paris, where it was published, with its text translated into several different languages, inviting performance by anyone who might be interested; but there is no evidence that it was ever sung. Fortunately for the musical world, Russian-American conductor Igor Buketoff (1915-2001) owned a copy of this Parisian publication, believed in the work, and pressed for its performance over the course of his life. Finally, after his death, the work received its first performance on April 11, 2014, in Portland, Oregon, by the Cappella Romana. It was performed in New York in an “open reading” by the Clarion Choir on the same weekend. Finally, just last week (October 24-29), it received it’s Russian premier, first in St. Petersburg, then in Moscow, in performances by the Clarion Choir. “Left behind” did not ending up meaning left forever.

A particularly poignant tragedy took place in the musical life of Maximilian Steinberg, a contemporary of the composers named above, who lived and worked in St. Petersburg, rather than in Moscow. Inspired by hearing a performance of Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil, he determined that he, too, would contribute to this repertoire, and he set to work composing a similar cycle, Passion Week, based upon historic chants and models. He continued working on it through the early years of the revolution, completing it finally in 1923. The anti-church stance of the revolutionaries had not started out as absolute, and Steinberg had hoped that his composition would be performed, at least as a concert piece; but by the time he had finished it, the work was condemned by the authorities, and the composer never heard it performed. More profoundly than for his Moscow colleagues, Steinberg’s work was left behind. He managed to get a copy of it to Paris, where it was published, with its text translated into several different languages, inviting performance by anyone who might be interested; but there is no evidence that it was ever sung. Fortunately for the musical world, Russian-American conductor Igor Buketoff (1915-2001) owned a copy of this Parisian publication, believed in the work, and pressed for its performance over the course of his life. Finally, after his death, the work received its first performance on April 11, 2014, in Portland, Oregon, by the Cappella Romana. It was performed in New York in an “open reading” by the Clarion Choir on the same weekend. Finally, just last week (October 24-29), it received it’s Russian premier, first in St. Petersburg, then in Moscow, in performances by the Clarion Choir. “Left behind” did not ending up meaning left forever.

How Chorale does it.

The startling fact remains-- year after year, Chorale’s performances are named in Chicago’s top ten lists by listeners whose business it is to recognize and acknowledge quality.

A long-time Chorale member has been hired to sing with one of the city’s top professional choral ensembles, and talked about the experience at Jimmy’s the other night, after Chorale’s regular Wednesday rehearsal. What follows is a conflation of her observations, and my own experiences on that side of the podium: Professional ensembles rehearse a minimal amount of time; management can’t afford more than that. Each singer shows up for every rehearsal, arriving for an on-time downbeat, ready to rumble. Their obvious professional musical preparation-- their high-level vocalism; the skill and assurance with which they read through a work the first time; their businesslike approach to learning their music and correcting their own mistakes; the efficient, no-nonsense atmosphere of the rehearsal—is assumed. From the very beginning, the ensemble is able to hit every point between pp and ff, and be responsible for each accelerando and ritardando. Language competence, at least in the standard pronunciations of Latin, English, and German, is rarely discussed. Neither the chorus master nor the conductor has to tell the singers much of anything, beyond what is written on the page-- they just tweak things; the singers take responsibility for everything. There is no hand-holding. The singers’ professional pride, and their love of music, forces them to do their best, and pressure from within the group is enough to make any who might feel like slacking off, to stiffen up.

Chicago Chorale, an amateur ensemble, is very different. We are proud of our accomplishments, but they happen within a very different environment. Most significantly, Chorale has to work a lot longer, and a lot harder, to reach its goals. We have a broad range of talent, experience, and facility within our group, and we need enough time to get everyone up to speed. I have to say everything many times, to make sure everyone has heard me, and understands me. Our singers have full non-musical lives, and devote a lot of time to their professions, their families, their other extracurriculars-- singing in a choir can by default be expendable to them. Professional choristers sing all the time, in any number of ensembles, and after years and years of professional preparation-- they expect to use their voices well, they expect to compete for their positions, they expect to be respected (and paid) for their expertise; Chorale members in some cases sing only once or twice a week, do not have established vocal techniques, do not read music with much fluency, and have to be reminded, and vocalized carefully, to make a good sound. Chorale singers in many cases do not take much responsibility for preparing outside of rehearsal; they hope and expect that magic will happen in the two and a half hours we spend together per week. They depend upon others in the group being more facile and leading the way. That is who we are; that is amateur, community-based choral music.

But the startling fact remains-- year after year, Chorale’s performances are named in Chicago’s top ten lists by listeners whose business it is to recognize and acknowledge quality. Do you ever reflect on the strangeness and incongruity of this? I surely do. Chorale is on to something. Through our messiness, we manage, as Robert Shaw would say, to build a nest good enough for the dove-- and as often as not, the dove lands there, and likes what he finds.

Our next series of concerts is November 18-19. Five more rehearsals. A professional ensemble would probably have five rehearsals total; for Chorale, it seems like we’ll never be ready, like we have too far to go before that nest is built. No nest, no dove. The good news is, we’ll get there. Our track record precedes us. Put those dates on your calendars, and plan to come hear some extraordinary music you have never heard before, prepared with love and care.

Guest Post: Chasing the Unicorn

By Managing Director (and soprano) Megan Balderston

By Managing Director (and soprano) Megan Balderston

Sometimes it is really easy to go into default mode, and default mode is a danger zone for singers. We had an exasperating rehearsal a couple of weeks ago because of it.

Some rehearsals are tough but satisfying; you work efficiently, people are focused and on the same page, and you leave feeling that you accomplished something. Then there is the unicorn rehearsal: that one that seems like a fantasy but does in fact occasionally happen—when everything inexplicably goes right and you leave on a high of fellowship, musicianship, and fun. Not two weeks ago. We went over and over things we ought to have known; I’m sure we didn’t get to everything; none of the voice parts were completely on. Boy, did it show. And our pronunciation—the vowels for which we hope we are known—were not there yet. The music by our June composers is individually compelling; together it will make a gorgeous concert. In our “e-blasts” and blog posts we talk a lot about what makes for good singing, most particularly language. I’ll get back to that later.

Learning music involves a lot of kinesthetic detail. It takes diligence, and precision, and intellectual curiosity. There may be people who don’t think about it that way—but I’m not one of them, and I share the stage with 60 people who feel the same way I do. There is, of course, learning the notes. Notes are important, certainly…and wrong ones are sort of beside the point. But we also have to feel an internal rhythm—the bones, so to speak. I had a college professor who used to have us march or dance along to music, just so that we would internalize all of the inner subdivisions of rhythm in each note. Bruce has his own tricks to make this happen. But the final thing upon which transcendent performances hinge, is communicating through our language. We can’t rely on the first two to make a complete choral work.

Almost our entire group comes to the party with a flat, Midwestern speaking voice. It’s not particularly attractive, but it’s the dreaded default mode for most of us. Maybe you remember the Saturday Night Live “Da Bears” skit? Now imagine those actors singing the Schubert Ave Maria in character and you have an exaggeration of the default we struggle against every day. To make ourselves understood in speaking, we exaggerate certain consonants and vowels. The letters R and A are good examples of this. But sing them in an exaggerated way and you sound like Gomer Pyle, or those fictional Bears fans.

One of my favorite voice teachers once said to me, “Come ON! Singing…is just talking. But stupid talking.” If we talked our vowels the way we should be singing them, we would sound at best Grey Gardens pretentious, and at worst stupid. It’s hard to compete against what you do naturally 12 hours a day, for the 3 hours we come together each week.

So here we all are, learning our 15th anniversary program. A program that will show our long-time followers and friends just how far we have come. A program in which we sing English, like British choir boys; we sing Latin; we sing French. We have only one person in the ensemble that grew up in the United Kingdom. The rest of us work hard to get those vowels pristine. As Bruce famously said in a rehearsal several years ago, “Deep in my heart, I know you can pronounce French. The French do it every day.”

Chicago Chorale is special because of that human need to strive for more; to create more than even we think we can. All beautiful things require some form of hard work and concentrated effort to get them that way. If we have to “stupid talk” to get our vowels to ring along with the beautiful music we are singing, so be it. We are jolting out of our daily default, and as such, we were due a giant leap forward. Thank goodness for that. Last week’s rehearsal was efficient, fun, and rewarding. Sometimes you take a step back before going two steps forward. Next stop: having a unicorn rehearsal!

Closing in on our performance

Confronted with the issues I have explored in the preceding weeks, plus a host of others, Chorale and I have made a lot of choices.

Confronted with the issues I have explored in the preceding weeks, plus a host of others, Chorale and I have made a lot of choices.

Chicago Chorale normally consists of sixty singers. Though enormous choruses have sung the Mass in B minor, and still do, the general trend has been toward smaller forces-- on occasion, just one singer per part. Frequently, even when larger groups sing it, a smaller group, termed concertists, will introduce many of the movements, will sing particularly difficult passages as solos, will even sing the more intimate movements entirely on their own. Sometimes, these concertists will be members of the choir; alternatively, they may be the soloists who also sing the aria and duet movements. This trend toward ripienist/concertist texture is supported by the scholarly literature.

Chorale is by no means a symphony chorus, but we are larger than ensembles which present the most praised, modern versions of the work. We could have chosen to bypass the work altogether, in honor of scholarship and in acknowledgment of the fact that we do not reflect cutting edge performance practice research-- but then we would be deprived of the glorious experience of learning and performing the work, and our audience would be deprived of the opportunity to hear it. So we chose to sing it, and to devote tremendous effort toward lightening our sound and articulation, while making the most of our full sound where it is needed and welcome.

We also chose to forego the ripienist/concertist procedure—which could have been interesting and appropriate for our forces. Such a procedure feels “professional” in the worst and most manipulative sense of the word; and I want Chorale to experience all of the music, each note, as an amateur event—an act of love. As Robert Shaw said—music, like sex, is too good to be left to the professionals. Again, this forces us to be more careful in our control of texture and dynamics than we would be if those issues were resolved through controlling the size of the forces.

Chorale has chosen to sing the Latin text with a German pronunciation. Most ensembles use the more common Italianate pronunciation, and have good results; and recent research indicates that the German pronunciation Chorale uses, based on modern German, is not necessarily the pronunciation Bach used or intended. So we can’t defend our choice on a secure, scholarly basis. But our choice does suggest the music’s German background. And I agree with Helmuth Rilling’s point that German consonants articulate more clearly than Italian, while German vowels narrow and clarify the vocal line, even for an entire section of singers, lending greater definition to Bach’s remarkably complex counterpoint. This is particularly necessary with a group of our size: clarity of pitch and line is far more important, in this music, than the beautiful, Italianate production of individual voices in the ensemble, which can actually work against an accurate presentation of Bach’s musical ideas.