Path of Miracles

Talbot is a major new voice for us choral geeks. I hope he composes more for us.

Few American choral music enthusiasts know anything at all about Joby Talbot, composer of Path of Miracles, a major a cappella choral work of which Chorale will perform a portion, on our upcoming June concert. So I’ll begin this post by quoting verbatim from a Wikipedia article:

"Joby Talbot (born 25 August 1971) is a British composer. He has written for a wide variety of purposes and an accordingly broad range of styles, including instrumental and vocal concert music, film and television scores, pop arrangements and works for dance. He is therefore known to sometimes disparate audiences for quite different works.

"Joby Talbot (born 25 August 1971) is a British composer. He has written for a wide variety of purposes and an accordingly broad range of styles, including instrumental and vocal concert music, film and television scores, pop arrangements and works for dance. He is therefore known to sometimes disparate audiences for quite different works.

"Prominent compositions include the a cappella choral works The Wishing Tree (2002) and Path of Miracles (2005); orchestral works Sneaker Wave (2004), Tide Harmonic (2009), Worlds, Stars, Systems, Infinity (2012) and Meniscus (2012); the theme and score for the popular BBC Two comedy series The league of Gentlemen (1999-2002); silent film scores The Lodger (1999) and The Dying Swan (2002) for the British Film Institute; film scores The Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005), Son of Rambow (2007) and Penelope (2008).

"Works for dance include Chroma (2006), Genus (2007), Fool’s Paradise (2007), Chamber Symphony (2012), Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (2011, revived 2012 and 2013) and The Winter’s Tale (2014), the latter two being full-length narrative ballet scores commissioned by The Royal Ballet and the National Ballet of Canada.

"Talbot premiered his first opera in January 2015 with the Dallas Opera. A one-act work entitled Everest and with a libretto by Gene Scheer, it follows three of the climbers involved in the 1996 Mount Everest Disaster."

So. He is young and full of talent; he creatively and fearlessly crosses boundaries and hears possibilities the rest of us hadn’t imagined. And he seems wonderfully energetic and creative.

Path of Miracles charts and describes the medieval pilgrimage across France and Spain to Santiago de Compostella, the final resting place of the remains of St. James. The work’s four movements are titled after the four main staging areas along the route-- Roncesvalles (at the foot of the Pyrenees), Burgos, Leon, and finally Santiago. The work’s librettist, Robert Dickinson, has constructed a narrative which includes quotations from various medieval texts, especially the Codex Calixtinus and a 15th century work in the Galician language called Miragres de Santiago, all held together with passages from the Roman liturgy and lines of original poetry by Dickinson himself. In mood, the work passes from opening excitement and euphoria, through fatigue, pain and suffering, suspicion and discouragement, desolation, to a growing sense of change, of freedom, of joy and light, until the final explosion of joy as the journey ends.

Chorale will present the third movement, Leon, which Talbot describes as a “Lux Aeterna”-- a musical imaging of the interior of the Cathedral of Leon. At this point in the work’s narrative the journey is more than half over, the pains and hardships of the earlier days have been overcome, and the pilgrims proceed almost hypnotically toward their goal. The movement begins with a refrain in C minor sung by four different soprano lines simultaneously—a canon against which the men’s voices sing a narrative, recitative-like line, describing the journey. By the end of the movement, the women’s refrain has modulated from minor to major. The choir sings, “Here daylight gives an image of the heaven promised by His love. We pause, as at the heart of a sun that dazzles and does not burn.”

I expect that anyone hearing this music for the first time will respond as I did, and still do. It is very beautiful, evocative, compelling; Talbot is a major new voice for us choral geeks. I hope he composes more for us.

Herbert Howells' Requiem

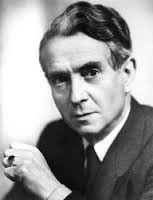

Herbert Howells (1892-1983) is one of my favorite English composers, up there with Tallis, Byrd, and Purcell.

Herbert Howells (1892-1983) is one of my favorite English composers, up there with Tallis, Byrd, and Purcell. Though quintessentially a composer of his time and place, specializing in the same genres as his colleagues during the late-nineteenth century and into the first half of the twentieth, he is, for me, very special, very individual: in his text setting and harmonic language; in the manner in which he builds and releases tension; and in the very heartfelt and authentic way these elements of his style express profound emotion while avoiding the formulas and conventions of his contemporaries—those aspects of this music we so easily and comfortably identify as “English.”

The compositional and performance history of his Requiem for a cappella choir (which Chorale will present in June) has been somewhat shrouded in mystery—a mystery which has contributed to a mythology about Howells, and his work, which recent, well-documented scholarship has not entirely corrected. A major pillar of that mythology states that Howells composed the Requiem in response to the death of his son Michael, at the age of nine, in 1935. We now know that the work was composed in 1932 or 1933, long before Michael’s death, and was intended for the choir of King’s College, Cambridge. For some reason, the score was never sent to King’s, and remained unknown until its publication in 1980, only three years before the composer’s own death. Howells himself came to associate the work with his son, and used major portions of it in his subsequent major work, Hymnus Paradisi, for chorus, soloists, and orchestra, a composition intended as his son’s memorial. I read that this larger work is considered the composer’s masterpiece, and have listened to it, and studied the score—and do not find that it has the power, the immediacy, of the original, a cappella composition. I can only be grateful that someone, perhaps Howells himself, realized that the smaller work had a unique beauty, and brought it to the public, rather than archiving it as a sketch.

Herbert Howells (1892-1983) is one of my favorite English composers, up there with Tallis, Byrd, and Purcell. Though quintessentially a composer of his time and place, specializing in the same genres as his colleagues during the late-nineteenth century and into the first half of the twentieth, he is, for me, very special, very individual: in his text setting and harmonic language; in the manner in which he builds and releases tension; and in the very heartfelt and authentic way these elements of his style express profound emotion while avoiding the formulas and conventions of his contemporaries—those aspects of this music we so easily and comfortably identify as “English.”

The compositional and performance history of his Requiem for a cappella choir (which Chorale will present in June) has been somewhat shrouded in mystery—a mystery which has contributed to a mythology about Howells, and his work, which recent, well-documented scholarship has not entirely corrected. A major pillar of that mythology states that Howells composed the Requiem in response to the death of his son Michael, at the age of nine, in 1935. We now know that the work was composed in 1932 or 1933, long before Michael’s death, and was intended for the choir of King’s College, Cambridge. For some reason, the score was never sent to King’s, and remained unknown until its publication in 1980, only three years before the composer’s own death. Howells himself came to associate the work with his son, and used major portions of it in his subsequent major work, Hymnus Paradisi, for chorus, soloists, and orchestra, a composition intended as his son’s memorial. I read that this larger work is considered the composer’s masterpiece, and have listened to it, and studied the score—and do not find that it has the power, the immediacy, of the original, a cappella composition. I can only be grateful that someone, perhaps Howells himself, realized that the smaller work had a unique beauty, and brought it to the public, rather than archiving it as a sketch.

John Bawden writes, “Howells’ music is much more complex than other choral music of the period, most of which still followed in the Austro-German tradition that had dominated English music for two centuries. Long, unfolding melodies are seamlessly woven into the overall textures; the harmonic language is modal, chromatic, often dissonant and deliberately ambiguous. The overall style is free-flowing, impassioned and impressionistic, all of which gives Howells’ music a distinctive visionary quality.

“The Requiem is written for unaccompanied chorus, which in places divides into double choir. There are six short movements which are organised in a carefully balanced structure. The two outer movements frame two settings of the Latin ‘Requiem aeternam’ and two psalm-settings. Howells reserves his most complex music for the Latin movements, in which he uses poly-tonality, chord-clusters and the simultaneous use of major and minor keys. In contrast, the psalm-settings are simple and direct, the speech-rhythms of the plain chordal writing arising out of the textual inflections.”

I came late to the Requiem. Although it became available to the public in 1980, and choral aficionados throughout the world rapidly became aware of it, I never even heard of it, never listened to a recording of it, until I began rehearsing it with Robert Shaw, in June 1998. Imagine my surprise, my pleasure, my total wonderment, as it unfolded before my eyes and ears. There is no choral work of the last 100 years that I like more. The performance ahead of us will mark the fifth time I have prepared it; the fact that I so eagerly return to it, is the best recommendation I can give it. If you do not know the work—prepare to be bowled over. No one expresses grief, and hope, better than Howells.

Spanish composer Javier Busto

The May 2016 ACDA Choral Journal features an entertaining, far-ranging interview with Spanish composer and conductor Javier Busto, two of whose motets Chorale will present in June.

The May 2016 ACDA Choral Journal features an entertaining, far-ranging interview with Spanish composer and conductor Javier Busto. Chorale will present two Busto motets, Ave Maria and O magnum mysterium, (works which Busto includes in a Top Ten list of his own compositions) at our June 11 concert; so I eagerly read the article when the magazine arrived the other day.

Busto has lived his entire life in Hondarribia, in the Basque region of Spain, where he was (until his recent retirement) a family medical doctor. He claims to be self-taught as a musician: “When I was eighteen years old, I created the first rock band here called the Troublemakers. It was really what I wanted from my musical life. The important thing to say is that I have never studied music: neither solfeggio, nor harmony, nor counterpoint, absolutely nothing!” Despite this, though, and despite his very active medical life, he has been remarkably successful in his avocation, publishing 419 choral compositions, several of which have received worldwide fame and popularity. He has also founded his own choir, Aqua Lauda, an ensemble of sixteen women.

The May 2016 ACDA Choral Journal features an entertaining, far-ranging interview with Spanish composer and conductor Javier Busto. Chorale will present two Busto motets, Ave Maria and O magnum mysterium, (works which Busto includes in a Top Ten list of his own compositions) at our June 11 concert; so I eagerly read the article when the magazine arrived the other day.

Busto has lived his entire life in Hondarribia, in the Basque region of Spain, where he was (until his recent retirement) a family medical doctor. He claims to be self-taught as a musician: “When I was eighteen years old, I created the first rock band here called the Troublemakers. It was really what I wanted from my musical life. The important thing to say is that I have never studied music: neither solfeggio, nor harmony, nor counterpoint, absolutely nothing!” Despite this, though, and despite his very active medical life, he has been remarkably successful in his avocation, publishing 419 choral compositions, several of which have received worldwide fame and popularity. He has also founded his own choir, Aqua Lauda, an ensemble of sixteen women.

Busto’s style is, by his own admission, Romantic, emotional, accessible. Describing his composition Ave Maria (which Chorale will perform), he says, “In 1985, I presented my Ave Maria at the Tolosa Competition. It was discarded because the jury thought it was too Romantic. According to them, my Ave Maria was a vulgarity. The jury was only composers, not conductors, and was very modern in its approach. I must say to you with modesty that Ave Maria, the same one that was discarded at the competition, is one of the most famous compositions in the entire history of choral music in Spain. It is the one that has sold the most copies, over 120,000. For me, Ave Maria is very important….after that, I decided not to present my works anymore in a composition competition. So, what I believe is important to the judges at composition competitions is that you make the jury think you are presenting something ground-breaking or something that will make someone think. It is not so important that you are writing something beautiful.”

Further on in the interview he states, “I always try to emote, for I believe it’s the most important thing. I don’t particularly like mathematical compositions that are too structured, those that are not going to move me or say anything to me. I work to compose things that possess emotion… my goal is to move people—to move myself, to move the singers, to move the conductor who is going to interpret the piece, and to move the audience. I believe this is my life.”

Don't assume from the above, that Busto’s works are easy to perform well. Many performances are featured on Youtube, and most of these performances are not very good-- they stress the accessible, sentimental side of Busto’s musical personality, but lack the technical underpinning, the clarity and precision required for successful performances. They end up sounding muddy, cluttered, out of focus. Focus and clarity are hard. Chorale is working hard to clarify his dense harmonic textures, and to free his rhythmic movement from ponderousness, to release his melodic arch and let it soar -- to capture the modest, understated crystalline quality of his voice, which is indeed very compelling. It is delicate, sensual music, and requires great care in preparation.

The article’s author tells us that Busto’s works were very popular in the United States during the mid-nineties, when many of them were programmed and recorded by leading choirs. But he slipped out of fashion (right about the time Morton Lauridsen and Eric Whittaker shot to prominence), and one rarely hears his works here anymore, though they continue to be popular in the rest of the world. I find them to be valuable and appealing, and am excited to present them in the context of our spring repertoire, which also includes weightier, more intellectually challenging repertoire. I expect you will like them; I hope you come to hear them!

The Fat Lady and the Boy

Two literary figures accompany me, one on either shoulder, whispering in my ears, when I make music. One is Seymour’s Fat Lady, from Salinger’s Franny and Zooey; the other is the little boy in The Emperor’s New Clothes.

Two literary figures accompany me, one on either shoulder, whispering in my ears, when I make music. One is Seymour’s Fat Lady, from Salinger’s Franny and Zooey; the other is the little boy in The Emperor’s New Clothes. I think we all know some version of this latter story: the Emperor, convinced that he is invincible, manipulated and puffed up by those round him, parades down the street clothed in what he imagines to be the finest outfit in the world, something so sublime that only those of special taste and understanding can appreciate it (or even see it). Those who see only his nakedness, blame themselves for being of a lower order, and go along, pretending to see the glory of his raiment, shouting his praises. The innocent (perhaps snotty and obstreperous) child speaks the truth: “But he’s naked!” The whole sham caves in and sanity takes over—but as adults we suspect the kid is actually taken out back and whipped, and that the charade continues long after the book’s cover has been closed.

Franny, a brilliant and promising young actress, at the end of her emotional rope, returns home from college to have a nervous breakdown. Her older brother Zooey, also an actor, tries everything he can think of to break her out of her self-absorption. He finally dredges up their shared image of the Fat Lady, a figure invented by their older brother, Seymour. The Fat Lady has thick, veiny legs, sits on a porch all day in the heat in an awful wicker chair, sweating, swatting flies, listening to the radio full blast; she probably has cancer. Seymour has told both Fanny and Zooey-- privileged, talented, special children-- to “do it” for the Fat Lady—to shine their shoes even when no one will see their feet, to perform their hearts out, to communicate. On the book’s final page, Zooey says to Franny, “There isn’t anyone out there who isn’t Seymour’s Fat Lady…don’t you know who that Fat Lady is?... It’s Christ Himself. Christ Himself, buddy.”

The presentation of great music is immensely, deeply challenging. It is difficult to do well. We are often tempted to deceive ourselves, our colleagues, the public, by settling for the appearance of a good job, which we then promote the heck out of with expensive publications, flowery prose, gorgeous venues, and broad claims about our competence. And this can work; the boy isn’t always present to pull us up short. Throwing glitter in their eyes can be very effective. Why not? We may not even be aware we are doing it; we may feel this is the way it is done. As Robert Shaw opined in anther memorable one-liner: “Anyone can buy a ticket; not many actually hear the music.”

But the Fat Lady really gets to me. Salinger is by no means considered a Christian writer—far from it. He uses and freely adapts ideas and images from many religions. Here, he pinpoints a central question with which all of them grapple: who are we to one another? How do we live together and care for one another? Does it matter? Franny has everything; but living for herself, focusing on her personal salvation, is not enough. It is in sharing her best with the lowest and least of these, that she refinds herself. And, presumably, is motivated to go on with her life, doing the best she can with her gifts.

The Fat Lady and the boy, in my mind, feed and support one another. Neither is complete without the other. If we believe that honest, face-forward immersion in the arts transforms our world, and reminds us that it is worth saving, then we have to believe that the Fat lady deserves them, needs them, as much as the rest of us.

The Wit and Wisdom of Mr. Shaw

"The arts, like sex, are too important to leave to the professionals."

"The arts, like sex, are too important to leave to the professionals." I heard this statement several times, over the years I sang with Robert Shaw. Musicians throughout the world will observe the 100th anniversary of Shaw’s birth on and around April 30 of this year, and many will share memories of his pithy anecdotes and one-liners. I will especially remember this phrase; it does stick with one. And it references directly the work I do: making choirs out of, and for, amateurs.

"The arts, like sex, are too important to leave to the professionals." I heard this statement several times, over the years I sang with Robert Shaw. Musicians throughout the world will observe the 100th anniversary of Shaw’s birth on and around April 30 of this year, and many will share memories of his pithy anecdotes and one-liners. I will especially remember this phrase; it does stick with one. And it references directly the work I do: making choirs out of, and for, amateurs.

Amateur, in its radical and most profound sense, means lover. Amateur musicians love what they do—whether they are paid to do it, or not. Members of Chicago Chorale sing in the group because they love the repertoire, they love getting together to sing it, they love working hard to get it right. I am able to program massive works—the Bach Passions, for instance, the major masses and requiems, the intricate and fiendishly difficult a cappella works of Arvo Pärt and Herbert Howells, the Rachmaninoff All Night Vigil on which we are currently working—because Chorale’s singers love these works, and are willing, even happy, to sweat through the long hours required to learn them, to become comfortable and fluent performing them. I am able to spend the time with the performers that the works require, and our audiences are able to hear the results of our work for reasonable ticket prices.

Chorale exists at least as much for its members, as it does for its audience. I don’t doubt for a moment, that choral singing, especially good, conscientious choral singing, is one of the best things one can do with ones time and energy. Grappling with the best that Bach has to offer brings one closer to the godlike mind and vision of Bach himself-- a state to which all of us should aspire. Embracing the passion and commitment of Rachmaninoff first-hand, sharing in the other-worldly vision of Pärt, can only change us in good ways-- and change our relationship with our culture, and the entire world around us.

Professional music—music for which performers are paid—is a good thing. I have been happy to perform at a high enough level, personally, to be paid for what I do. I am grateful. And I know the pitfalls of such professionalism. I have too often gone into performances under-rehearsed because management could not afford sufficient rehearsal time; I have too often sung with and under musicians whose work I did not enjoy or respect, because I needed the money offered me. I have too often performed repertoire which did not seem worth the effort expended to present it, and about which I felt little pride or sense of accomplishment. I have too often entertained the nagging feeling that the magic I experienced as a child, and as a student, when the vast and wonder-filled world of music opened up to me, was no longer a major part of what I was doing.

I never feel this disappointment when I work with Chorale. Idealism, and love, predominates in this work. I see the awakening of wonder in the eyes of my singers, experience the grateful response of our audience, and I know that what we are doing is right where I want to be. Mr. Shaw had it right.

It's All About the Language

Language sets vocal music apart from instrumental music—and may even turn it into an entirely different art form. Singers undergo training and preparation that is very different from that experienced by instrumentalists.

Language sets vocal music apart from instrumental music—and may even turn it into an entirely different art form. Singers undergo training and preparation that is very different from that experienced by instrumentalists. We learn, and warm up with, the basic Italian vowels—a, e, i, o, and u—but that’s only the beginning; not only do we have many more vowels than these to learn, but we have to relearn even the basic five as we move from language to language. [a] in Italian is very different from [a] in Russian. And then there are the consonants, bewildering enough in our own language, but really mystifying when moving far afield-- “what do you mean, isn’t T just T? And L just L? ” The looks of blank incomprehension that greet critiques of the manner in which T and L are pronounced, are priceless.

And the various sounds of language, the phonemes, are just the beginning. Singers have to sing as though they understand what the language means, too. Ideally, all of the singers in a choir would be linguists, reading and speaking numerous languages, ears and brains open to new sounds, new meanings. The truth is far from that. So, when tackling a major work in a foreign language, the conductor has to arrange, in advance, to spend a considerable amount of rehearsal time on extra-musical matters, and to enlist extra-musical help. The work we are currently preparing, Rachmaninoff’s Vespers, sets a text entirely in Old Church Slavonic—a language in which I have no particular proficiency. The editor of the edition from which we are singing has devised a  helpful, comprehensive transliteration and pronunciation system—he even sends out a CD of the text spoken by a knowledgeable speaker—but Chorale goes further, and has a language coach, Drew Boshardy, present at all of our rehearsals (he also sings with the group), who reads the text, has the singers repeat it, corrects their errors, listens to them sing it, corrects them again—and is vigilant throughout the rehearsal process, jumping in with comments whenever he hears something questionable. He also points out the meanings of specific words, and guides us in word accents and the overall mood of particular phrases.

helpful, comprehensive transliteration and pronunciation system—he even sends out a CD of the text spoken by a knowledgeable speaker—but Chorale goes further, and has a language coach, Drew Boshardy, present at all of our rehearsals (he also sings with the group), who reads the text, has the singers repeat it, corrects their errors, listens to them sing it, corrects them again—and is vigilant throughout the rehearsal process, jumping in with comments whenever he hears something questionable. He also points out the meanings of specific words, and guides us in word accents and the overall mood of particular phrases.

Drew has a degree in Slavic languages from the University of Chicago, and his help is invaluable; if we didn’t have him, we’d have to find someone much less convenient. We make the same sort of arrangements when we sing in German, French, Norwegian; care for language is a very important part of the Chicago Chorale experience. Agreement on vowel color is essential to good intonation; clear, uniform consonants define rhythm. And the meaning of the text determines interpretation. Even if listeners in the audience are not aware of what we are doing, or if a particularly juicy acoustical space obscures the details we so carefully stress, the precision and care with which we present the language, and the music, still comes through. We sound together, and committed.

Singers, and choirs full of singers, stand to learn a great deal from instrumentalists: from their precision, their intonation, their careful control of dynamics and color. Often, when preparing the major Bach works, I talk in rehearsal about the way in which string players would accent or phrase a certain passage, simply because of the characteristics of their instruments. But I have often noticed, as well, in the instrumentalists’ printed parts, that some players write the words in at crucial points, to guide them in the choices they make—and I rejoice to see this. Singers bring something very special to a musical preparation. We all profit through learning from one another.

Guest Blog: Sam Martin

I work as a strength & conditioning coach, so I’m used to training for, and overcoming, physical challenges. Wednesday nights, during this rehearsal cycle, have become another workout.

Singing the Rachmaninoff All-Night Vigil is a uniquely physical challenge among Chorale’s repertoire. Every composer brings different obstacles: Bach requires mathematical precision to get “the grid” (as Bruce calls it) of notes and rhythms just right, while modern composers like Schoenberg ask singers to come in with perfect intonation on difficult intervals and non-traditional harmonies. No one tests the singer’s posture, breath, and vocal technique quite like The Rach.

Singing the Rachmaninoff All-Night Vigil is a uniquely physical challenge among Chorale’s repertoire. Every composer brings different obstacles: Bach requires mathematical precision to get “the grid” (as Bruce calls it) of notes and rhythms just right, while modern composers like Schoenberg ask singers to come in with perfect intonation on difficult intervals and non-traditional harmonies. No one tests the singer’s posture, breath, and vocal technique quite like The Rach.

I have spent my six working years since graduating from college working as a strength & conditioning coach, so I’m used to training for, and overcoming, physical challenges. Wednesday nights, during this rehearsal cycle, have become another workout. Rachmaninoff requires the baritone part (which I sing) to spend long stretches singing low notes: B, A, G, F—then builds quickly up an octave to Cs, Ds, and Es. There is a gravitational effect from spending a long time in the bottom of the register, and a high D never feels so high as it does during this piece. These vast shifts in register allow the singer no chance to rest his technique.

To survive this piece, one has to breathe correctly, and maintain enough intraabdominal pressure to be able to go big on a moment’s notice. In a lot of repertoire one can get away with more or less chilling out between difficult passages. Try that on Rachmaninoff and you’ll go flat and end up behind the beat, trying to figure out what happened.

It’s reminiscent to me of the CrossFit workouts I used to do that combined seemingly opposite tasks like heavy lifts with running. I’d come in after a run, breathing fast with a high heart rate and all of a sudden have to lock in my posture to keep my back flat while lifting a heavy barbell off of the ground. Even that was easier than singing Rachmaninoff, though.

Why? Rachmaninoff combines the physical challenge of singing with the mental (and for the face, mouth, and tongue physical) challenge of correctly enunciating the nearly unpronounceable Old Church Slavonic language. I don’t sing in Chorale, though, because it’s fun or easy; I sing in Chorale because it’s worth it. On March 19th & 20th when this all comes together, it will be worth all the physical and mental labor it took to build.

Martin Luther King Day, 2016

A college friend emailed me this morning, asking what I remembered about Martin Luther King’s assassination.

A friend emailed me this morning, asking what I remembered about our college’s reaction to, and observance of, Martin Luther King’s assassination (we were first years at the time, and roommates). It was a huge event, certainly, and a big shock to all of us—one of a number of unsettling occurrences during our college years, which largely defined who we became. But I don’t remember the words, the speeches, the assemblies, the dormitory and dining hall discussions. It was a long time ago, and a lot of water has flowed over that dam. What I remembered, I found, when asked, is the music. I remember the songs we sang—both the informal community sings, of protest songs and spirituals, and the formal ”In Memoriam Martin Luther King” concert my choir later sang. I remember the people with whom I sang, and the music we sang—the words and the melodies; I remember the concert hall, and the look of the audience. I remember the highly charged emotions of our conductor, who spoke of King as though he were a close personal friend. I even remember the poster and printed program, nearly fifty years later, though I did not save copies.

Music has this power. Especially, for me, vocal music. And especially the personal performance of music. Significant events, relationships, locations-- most seem anchored in my memory, and in my convictions, by the music that accompanies them. I suspect most people are like me, in this respect, and that this is not a function of special capacity or professional choice. I remember my 99-year old grandmother being called back to the here and now, when her pastor sang “Tryggare kan ingen vara” to her, unlocking a flood of childhood memories and stories, which she so eagerly shared. I will always remember the death of Tony Garner, announced to the choir just before Robert Shaw conducted a performance of the Howells Requiem, in Greenville, South Carolina. I remember my summers working as a counselor at Camp Buckskin, singing my cabin of ten little boys to sleep, night after night. And sitting on a point jutting into the water on Eddy Lake at sunset, singing “L’heure exquise” to myself as the sun set. Elsa Charlston and Steve Hendrickson performing “Let the bright seraphim” at our wedding. Holding hands with the singers on both sides of me while my college choir sang the Vaughan Williams Mass in G. Hearing my mother sob while ironing in the kitchen, listening to La Boheme on the radio. Singing to my daughter as she lay in a coma, after a car/bike accident during her senior year of high school.

A friend emailed me this morning, asking what I remembered about our college’s reaction to, and observance of, Martin Luther King’s assassination (we were first years at the time, and roommates). It was a huge event, certainly, and a big shock to all of us—one of a number of unsettling occurrences during our college years, which largely defined who we became. But I don’t remember the words, the speeches, the assemblies, the dormitory and dining hall discussions. It was a long time ago, and a lot of water has flowed over that dam. What I remembered, I found, when asked, is the music. I remember the songs we sang—both the informal community sings, of protest songs and spirituals, and the formal ”In Memoriam Martin Luther King” concert my choir later sang. I remember the people with whom I sang, and the music we sang—the words and the melodies; I remember the concert hall, and the look of the audience. I remember the highly charged emotions of our conductor, who spoke of King as though he were a close personal friend. I even remember the poster and printed program, nearly fifty years later, though I did not save copies.

Music has this power. Especially, for me, vocal music. And especially the personal performance of music. Significant events, relationships, locations-- most seem anchored in my memory, and in my convictions, by the music that accompanies them. I suspect most people are like me, in this respect, and that this is not a function of special capacity or professional choice. I remember my 99-year old grandmother being called back to the here and now, when her pastor sang “Tryggare kan ingen vara” to her, unlocking a flood of childhood memories and stories, which she so eagerly shared. I will always remember the death of Tony Garner, announced to the choir just before Robert Shaw conducted a performance of the Howells Requiem, in Greenville, South Carolina. I remember my summers working as a counselor at Camp Buckskin, singing my cabin of ten little boys to sleep, night after night. And sitting on a point jutting into the water on Eddy Lake at sunset, singing “L’heure exquise” to myself as the sun set. Elsa Charlston and Steve Hendrickson performing “Let the bright seraphim” at our wedding. Holding hands with the singers on both sides of me while my college choir sang the Vaughan Williams Mass in G. Hearing my mother sob while ironing in the kitchen, listening to La Boheme on the radio. Singing to my daughter as she lay in a coma, after a car/bike accident during her senior year of high school.

I grew up surrounded by music, all kinds of music: some of it great, some of it not so good, all of it startlingly memorable. I realize now that the richness of my life’s experience, and my memories of that experience-- joy, sorrow, tragedy-- all live in my memory accompanied by music. The adults I knew best, and now care most about, were my music teachers and conductors; the high school and college friends with whom I have maintained contact sang in choirs with me. The younger people with whom I have been able to form relationships, have sung with me, or for me. It occurs to me that I would be almost nobody, inarticulate and disconnected, had I not music to create a life for me.

Facebook has featured Dr. King’s favorite song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” several times today, along with the story about his calling Mahalia Jackson on the phone and asking her to sing it to him. Along with recording of both Mahalia Jackson and Reggie Mobley singing it. I’m sure these recordings, and this story, will become defining features of my remembrances, from now on. Music has that power.

Embarking on Sergei Rachmaninoff's Vespers

Russian choral music culminates in Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil.

After a successful autumn (the Chicago Tribune’s music critic John Von Rhein designated our Arvo Pärt at Eighty concert “the Year’s Finest Choral Performance”), Chorale has embarked on preparations for our March presentation of Rachmaninoff’s Vespers. As preparation for this event, I quote from program notes compiled by Chorale alumnus Justin Flosi, seven years ago: “Written at the height of the renaissance of Russian sacred choral music, Rachmaninoff’s few sacred works remain the unrivaled jewels in the crown of the Orthodox musical tradition and epitomize the work of the New Russian Choral School. Composers of the school (including Kastalsky, Gretchaninoff, and Chesnokov) drew their inspiration from Old Church Slavonic chant and Russian choral folk song, departing from a century and a half of domination by Italian and German models. Led by musicologist Stepan Smolensky, who headed the Moscow Synodical School of Church Singing and pioneered the historical study of ancient chant, these composers created an entirely Russian choral style marked by an endless array of dynamic nuances and choral timbres.

“Rachmaninoff’s Vespers (All-Night Vigil, op. 37) was composed over just two weeks in January and February of 1915 and dedicated to Smolensky, the composer’s tutor. Johann von Gardner has proclaimed it a “liturgical symphony,” and indeed, Rachmaninoff masterfully exploits the New School’s technique of “choral orchestration,” varying the choral color extensively, dividing the choir into as many as eleven parts, calling for precise articulations, and dictating a vivid spectrum of dynamic gradations. From the tradition of Russian folk song, Rachmaninoff borrows the technique of “counter-voice polyphony,” skillfully integrating into his composition parallel voice-leading, melodic lines above a drone, and imitation between a constantly changing number of voices. And yet, Rachmaninoff’s dazzling technique never calls attention to itself; rather, it serves at all times to sustain the sacred text in its position of prime importance.

“Rachmaninoff’s Vespers (All-Night Vigil, op. 37) was composed over just two weeks in January and February of 1915 and dedicated to Smolensky, the composer’s tutor. Johann von Gardner has proclaimed it a “liturgical symphony,” and indeed, Rachmaninoff masterfully exploits the New School’s technique of “choral orchestration,” varying the choral color extensively, dividing the choir into as many as eleven parts, calling for precise articulations, and dictating a vivid spectrum of dynamic gradations. From the tradition of Russian folk song, Rachmaninoff borrows the technique of “counter-voice polyphony,” skillfully integrating into his composition parallel voice-leading, melodic lines above a drone, and imitation between a constantly changing number of voices. And yet, Rachmaninoff’s dazzling technique never calls attention to itself; rather, it serves at all times to sustain the sacred text in its position of prime importance.

“The All-Night Vigil service was introduced to Russia in the fourteenth century. In the words of Vladimir Morosan, it is a “curious liturgical concatenation” combining the services of Vespers, Matins, and Prime. Celebrated on the eves of holy days, it lasted from sunset to sunrise in the medieval church (although modern reforms have shortened the service). Remarkably, Rachmaninoff sets the entire thing—all fifteen hymns, psalms, and prayers of the Resurrectional Vigil. Though deeply spiritual, Rachmaninoff was at odds with the organized religious establishment (which opposed his marriage to his first cousin, Natalie Satin) and not intimately familiar with the traditional musical settings of the Church’s liturgy. This may help explain his original and inventive approach in the All-Night Vigil.

“Rachmaninoff’s use of melodic material is both innovative and exhaustive, at once original and steeped in tradition. Drawing from all three ancient chant traditions (Znammeny, meaning “notated with neumes,” Greek School, and Kiev School), nine of the fifteen movements are based on actual chant melodies. For the remaining six, Rachmaninoff composed new material, inspired by chants; he called these movements “conscious counterfeits.” The resulting fusion of old and new material overflows with an intensely expressive melodic richness. As the voices by turns rise heavenward and sink into the depths, Rachmaninoff portrays the essence of humankind’s worship of the Divine, from its most exuberant exultation to its most sincere supplication.

“Such sumptuous sounds illumine the epic grandeur of the events commemorated in the All-Night Vigil. After the opening call to worship, the Vespers section depicts the Creation and the incarnation of Christ. The Matins portion turns to a celebration of the central event in Christian cosmology: Christ’s resurrection. Thus, spiritually, liturgically, textually, and musically, the work operates on an immense and expansive scale. Francis Maes positions it at the summit of the Orthodox tradition, stating that, “The work satisfies all liturgical demands, but goes beyond them in the same way that Bach’s B Minor Mass and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis do.” As those works serve as capstones to their respective traditions, so Russian choral music culminates in Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil.”

I could not have said it nearly so well.

Start Your Own Choir

Twenty years ago I could not have imagined I, and the choirs I conduct, would be in this place today.

Twenty years ago—January 1996—I sat in a hotel room in New York, talking with my wife on the phone, in complete despair about my professional future. We were attempting to make a life commuting between her university in Virginia, and mine in Chicago—with a four-year old child in the middle. Due to a random collision of events— a blizzard in Virginia, several concerts in Chicago, a week in New York with the Robert Shaw Festival Singers—we had not seen each other in three weeks. This clearly was not working; we would have to make a big decision, and one of us would have to give in, to preserve our marriage and family. My roommate, Harry Keuper, was waving his arms in the background, drawing his finger across his throat, whispering frantically “Don’t make decisions over the phone!” I finally did get off the phone, and Harry said, “I’ll call Robert” (Harry had access)—and shortly, sure enough, Robert Shaw was on the phone, telling me, “Forget about academic choral music. Start your own choir. That’s what our country needs.” I was wed to the security represented by the fifteen years I had spent conducting choirs and teaching voice on the college level. I could not imagine doing as Mr. Shaw suggested (more like, commanded). I did give up my job and move to Virginia— and proceeded to struggle for five years with an ill-fitting adjunct position, feeling increasingly that my professional life had come to an end. We decided to move back to Chicago—and within one month of our August, 2001, arrival, I had given in to Mr. Shaw’s dictum, and started my own choir. A friend from the Shaw program, Charles Bruffy, conducted a group named “Kansas City Chorale,” and I decided to copy him—and so was born Chicago Chorale.

Well, it worked. I wish Mr. Shaw were alive to see it, and to see that someone, at least, had done what he was continually telling us to do. I had never previously thought of myself as an entrepreneur—but it was learn, or die; and I had little choice. I got on the phone, got on email, contacted singers, who contacted other singers; I located a rehearsal space; I scheduled a performance for December; I got some music together; and then held my breath as twenty-four singers arrived for our first rehearsal and began to sing. I had no diagram, no future plans, no specific goals, and I rather hated that I was being forced into this—but we did it, and it worked.

Well, it worked. I wish Mr. Shaw were alive to see it, and to see that someone, at least, had done what he was continually telling us to do. I had never previously thought of myself as an entrepreneur—but it was learn, or die; and I had little choice. I got on the phone, got on email, contacted singers, who contacted other singers; I located a rehearsal space; I scheduled a performance for December; I got some music together; and then held my breath as twenty-four singers arrived for our first rehearsal and began to sing. I had no diagram, no future plans, no specific goals, and I rather hated that I was being forced into this—but we did it, and it worked.

Five years later, a group of male undergrads from the University of Chicago approached me and asked if I would start a choir for them, too. They didn’t really know what they wanted; they just wanted something that the university did not offer. Well, it was the same thing: find some singers, find a place to rehearse, put some music together, schedule a performance, and again hold my breath as twelve guys straggled in, as unsure of what they were asking, as I was of what I could do for them. And again, it worked. Chicago Men’s A Cappella saw the light of day.

Five years later, a group of male undergrads from the University of Chicago approached me and asked if I would start a choir for them, too. They didn’t really know what they wanted; they just wanted something that the university did not offer. Well, it was the same thing: find some singers, find a place to rehearse, put some music together, schedule a performance, and again hold my breath as twelve guys straggled in, as unsure of what they were asking, as I was of what I could do for them. And again, it worked. Chicago Men’s A Cappella saw the light of day.

So I celebrate two anniversaries this year: Chorale’s fifteenth, and CMAC’s tenth. Twenty years ago I could not have imagined I, and the choirs I conduct, would be in this place today—I had far different plans and ambitions, back then. But I found myself at a professional impasse, and felt I had no choice but to follow Mr. Shaw’s rather blunt, unhelpful advice. I honor him for giving it: his seeds fell on fertile ground. And I honor the singers and listeners who have supported his vision, and helped it to bear fruit. Both ensembles will celebrate their anniversaries this spring with gala reunion events; I hope you will come and participate, and celebrate the words and vision of a man who spoke so compellingly to me twenty years ago, and continues to speak to us in the choral music profession, from beyond the grave.

Spiritual Minimalism's Grand Old Men

The original "spiritual minimalists" are strikingly different from one another, with distinctive voices, and do not regard themselves as any sort of unit.

The most successful and well-known composers on our coming concert, aside from Pärt himself, are Henryk Górecki (1933-2010) and John Tavener (1944-2013). They, along with Pärt, are most often referred to as the “spiritual minimalists” whose work has attracted large audiences and radically altered the course of choral music composition. They are strikingly different from one another, with distinctive voices, and do not regard themselves as any sort of unit. What they have in common is that they compose from positions deeply rooted in personal religious faith, finding inspiration in sacred, liturgical texts; and they have all moved from somewhat complex, academic compositional practices in their earlier years, toward simpler, more straightforward and emotionally evocative styles as they have matured.

Górecki was a leading figure in the Polish avant garde during the post-Stalin years, composing serial works during the 1950s and 1960s which were characterized by dissonant modernism, influenced by other modernist composers such as Luigi Nono, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Karlheinz Stockhausen. By the mid-1970s, however, he had shifted toward a less complex sound, one characterized by large, slow gestures and the repetition of small motifs, exemplified by the Amen (1975) which Chorale will sing. He achieved sudden, worldwide fame in 1992, when his Third Symphony, subtitled Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, commemorating the memory of those who died during the Holocaust, became a worldwide commercial and critical success, selling more than a million recordings.

Like other composers on this program, Górecki was politically active, and in constant conflict with the Polish Communist authorities, whom he described as “little dogs always yapping.” As a professor of musicianship, composition, and orchestration at the Academy of Music in Katowice, he had a reputation for bluntness and ruthlessness, telling his students, “If you can live without music for two or three days, then don’t write…It might be better to spend time with a girl or with a beer.” A devout Roman Catholic, he resigned from his teaching position in 1979 to protest the government's refusal to allow Pope John Paul II to visit Katowice; when the pope finally visited Poland, in 1987, Górecki composed his motet Totu tuus in honor of the visit.

British composer John Tavener enjoyed a life characterized by far less external conflict and stress than the composers who matured and worked in Soviet bloc countries. His family was comfortably affluent, he attended good schools, and experienced early recognition and success for his compositional efforts. But, like Pärt and Górecki, he experienced a radical change in his fundamental compositional ideas, from his earlier works in a style reminiscent of Messiaen and Stravinsky, toward a sparser, more diatonic, contemplative style, characterized by textural transparency-- described by composer Johan Rutter as being able to "bring an audience to a deep silence.”

Tavener converted to the Russian Orthodox Church in 1977; thereafter, Orthodox theology and liturgical traditions became a major influence on his work. He was particularly drawn to its mysticism, studying and setting to music the writings of the Orthodox church fathers. In later years, he explored a number of other religious traditions, including Hinduism and Islam. In an interview with The New York Times, Tavener said: "I reached a point where everything I wrote was terribly austere and hidebound by the tonal system of the Orthodox Church, and I felt the need, in my music at least, to become more universalist: to take in other colors, other languages." Chorale will sing Song for Athene (1993), which sets a text by Mother Tekla, a Russian Orthodox abbess who was Tavener's long-time spiritual adviser. Song for Athene brought Tavener international exposure and fame when it was performed at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997.

Jan Sandström and Urmas Sisask

The era of spiritual minimalism has encouraged composers and performers to range widely, and to explore many sources—musical, religious, and philosophical-- in search of inspiration.

The era of spiritual minimalism has encouraged composers and performers to range widely, and to explore many sources—musical, religious, and philosophical-- in search of inspiration. One recurring theme in the biographies of our November concert composers is the interest in early church music—especially Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony. The composers are drawn to the seeming simplicity of this music, to its starkness, to its capacity to inspire emotion and wonder out of almost nothing. I remember rehearsing Pärt and Gorecki pieces with Robert Shaw, and his somewhat frustrated comment that their music reminded him of crawling back into the womb. That is a strangely is a valid description of what the composers are attempting: a radical return to the most fundamental materials and meaning of music, and to the meaning of silence—where does music come from? Why do we do it?

Two of the most experimental composers on our program are Jan Sandström (b.1954) and Urmas Sisask (b.1960). Sandström was born in the far North of Sweden, at the top of the Gulf of Bothnia, near the town of Piteå, and is now Professor of Composition at the College of Music there. I spent several weeks at that school, about twenty-five years ago, and found it to be a very surprising and inspiring place—an island of intense energy and creativity in the midst of lakes, birch trees, and silence. I was there during the eternal light of summer; I cannot imagine what it must be like during the winter. Such an environment must inevitably invite one to question the patterns and assumptions that sustain life in more normal settings. Sandström is most famous for his Motorbike Concerto for trombone and large orchestra, and for his setting of Es ist ein Ros entsprungen for 8-part chorus at a glacially slow tempo. He began his compositional career writing in an austere, theoretical, sophisticated, densely-constructed idiom, making using of spectral techniques (composition based on analyses of overtone registers). Then, in the late 1980’s he shifted toward a more minimalist style. A review of his 2008 Rekviem summarised: "99% Pärt, 1% Bach". Gloria, the work we will sing on our program, falls squarely within this latter style.

Estonian composer Urmas Sisask graduated from the Tallinn Conservatory in 1985, and, unlike his compatriot Pärt, has spent his entire compositional life in Estonia, focusing on the culture and folk music of that particular locale. He is described as both composer and amateur astronomer, but these two activities are in fact closely interlinked. He lives in the small, remote village of Janeda, where he has built his own observatory, and where he gives concerts and lectures in his Musical Planetarium situated in the tower of an old manor house. He has worked out theoretical sound values for the rotations of the planets in the solar system. This reduces to a planetal scale' of five tones: C-sharp, D, F-sharp, G-sharp and A. This scale forms the melodic and harmonic basis for many of his later compositions, though not for Benedictio, the work Chorale will present. Benedictio reflects, rather, another of Sisask’s strong interests, the shamanic pre-Christian religion indigenous to the Baltic region, and the folk music associated with it. He has developed his own, expressive musical language based upon these influences, which, with its constant reference to perfect fourths and fifths, is harmonically closer to old church modes than to the diatonic, major/minor system utilized by Pärt and Sandström. Benedictio is set in an incantatory style, based upon repeated, hypnotic rhythmic and melodic patterns, building to enormous, almost bacchanalian climaxes, unlike anything heard in the gentler and subtler music of our other chosen composers.

Rihards Dubra and Vytautas Miškinis

Some of the composers featured in Chorale’s upcoming Arvo Pärt at Eighty concert are veritable rock stars in today’s classical music world.

Some of the composers featured in Chorale’s upcoming Arvo Pärt at Eighty concert are veritable rock stars in today’s classical music world. Pärt himself, John Tavener, and Henryk Gorecki, have cross-over appeal; CDs of their music sell millions of copies. Other composers on our program work in relative obscurity, but their music is no less worthy of consideration.

Latvian composer Rihards Dubra was born in Jurmala, on the Baltic, about 30 miles from Riga, in 1964. He studied at the Emils Darzins music school in Jurmala, where he now teaches, and the Latvia Music Academy, specializing in composition. He teaches theory, is organist of Mater Dolorosa Church in Riga, and is a member of the Schola Gregoriana Rigensis singers. Though he grew up in the secular milieu imposed by the Russians during the years Latvia was a member of the USSR, Dubra has devoted himself exclusively to the composition of sacred music, citing his admiration for the works of Arvo Pärt and John Tavener. He has written, “As faith is the only purity in this world, I cannot imagine anything better than to write only sacred music… I doubt that the energy I feel inside me is mine. I do not create music—I just write down what has been sent to me.” Elsewhere, he has written, ‘’Just as everyone has their own pathway to God, so every composer has his own pathway to emotion in music, and through that—also to God.” He says that for a long while he has had a great love of Gregorian chant and the music of the Middle Ages, and that these provide his favorite inspiration, but “through the view of a man who lives in the present century.”

Even before Latvia regained its independence in 1990, and public expressions of religious faith were once again allowed, Dubra was setting liturgical texts in Latin. These works were conceived for concert audiences whose experience of sacred music, due to the anti-religious nature of the Soviet state, was not informed by theological or liturgical understanding. Dubra feels that emphasis on careful text-setting would be largely meaningless in this context, and prefers to emphasize the spiritual and emotional aspects of his settings—“People should not always understand the text exactly because its meaning is encoded in the music … my main task is to work on people’s subconscious level, people’s emotional level.”

Vytautas Miškinis was born in Vilnius, Lithuania, in 1954, and is the Artistic Director of the Azuoliukas Boys’ and Men Choir, Professor of Choral conducting at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and President of the Lithuanian Choral Union. Although by training and experience he is primarily a music educator and conductor, his more than 700 choral compositions, both sacred and secular, have become increasingly well-known and respected in the twenty-first century. Unlike Dubra, who claims to care less for clear text setting that for a spiritual and emotional subtext, Miškinis’ works display close connection between music and text. He writes, “The essential for me is the meaning of the lyrics. The content. For that reason I accept any means of expression that refers to the meaning of a word.“

Like most current Baltic composers, especially those who specialize in choral music, Miškinis utilizes an essentially diatonic vocabulary, with much overlaying of harmonies and colored cluster-chords. His characteristic sound includes many perfect fifths and fourths reinforcing the harmonic series. Lithuania is largely Roman Catholic, and Miškinis was raised in this faith, to the extent that this was possible during the Soviet era. Although he does not consider himself a strong believer, he is drawn to sacred, liturgical texts for their universal ideals, their “unique poetry”. He sets primarily Latin texts, because they are the most universally recognized and accepted, and because he prefers Latin sounds for the singing voice.

Reviewing a recent CD compilation of Miškinis’ works, a reviewer in Gramophone wrote, “His music has a timeless and highly atmospheric quality. Textures and nuances are used with great perception … the effect on the listener is best summed up as being one of “contemplative meditation.”

A Good Potato

I have been thinking a lot lately about my voice teacher, Norman Gulbrandsen, who died five years ago.

I have been thinking a lot lately about my voice teacher, Norman Gulbrandsen, who died five years ago. Interestingly, when I think about mentors and teachers who had the greatest impact on me, voice teachers are every bit as important as choral conductors—and Norman is right at the top of the list. One would be hard-pressed to ascribe a method or technique to him—mostly, he listened and commented, and had you try it again. His ear for what you should be doing, for what your voice and body should be accomplishing, was his great gift. It was almost unerring. And he never gave in, at least with me-- I was by no means one of his more gifted singers, but he always took me seriously, pushed me, encouraged me to exceed my limitations and personal expectations, recognized my strengths and supported my accomplishments. I always looked forward to my lessons, was happy to see him; and I always regretted I could not be a better singer, and give him more of what he wanted.

Norman and I shared Norwegian heritage—and this was a constant source of good-natured banter. He would address me as Norske gute (Norwegian boy) when I showed up for my lesson, and ask what obscure Grieg song I wanted to work on this week (I had a lot of them). More than the banter, though, we shared a certain, typical outlook toward quality of work. He was always critical of the more precious expressive habits I picked up through listening to recordings and attending master classes, and would tell me, “Just put one note in front of the other, and make sure they are all good notes.” One memorable day he really dug deep, and said, “I love potatoes. Good potatoes. Give me a good, solid potato every time; I don’t need any gravy on it. In fact, the older I get, the less I care about gravy at all, and the more satisfied I am with a solid, good potato.” Knocked me flat. I remember the day, his face, the face of the accompanist, Kit Bridges-- a Joycean epiphany. I understood, like I had never understood before then. He was talking about Elly Ameling’s iron fist in the velvet glove; about Robert Shaw’s count singing; about Weston Noble’s insistent, repetitive lining up of vowels and tuning of chords—but in a language which was peculiar to where I came from, language my parents and grandparents would have understood. Just give me the real potato; the rest will follow.

He had a strange faith that musical sensitivity and expressiveness were innate-- that if a singer really understood the words—not just literally, but poetically--, understood the harmonies, understood the melodic direction, the music would just happen; his job was to train and refine the physical mechanism through which this mystical thing could be accomplished. Week after week he would tell me, “You don’t have to convince me that you are musical; you over-express when you try to do that. And that bends your voice out of shape. Trust yourself and your love of these words and music. Just put one note in front of the other, and you’ll be fine.”

More than a guide to good singing, his illustration was a life lesson. Be solid, be straightforward; stand behind your work. Know where you stand, and be unassailable in that place. Don’t hide shoddy work under gravy—and don’t be fooled by anyone elses gravy, either. He gave me a lot of courage, when I needed that encouragement most sorely. I grow quite a lot of potatoes in my garden, each summer, in honor of him; and when I come across a particular beauty, I think of him. I’d love to be able to take it to his studio and hand it to him—a good, solid potato. I stand behind this.

Knut Nystedt-- an early minimalist?

This is undoubtedly some of the best choral music currently being written, and we are thrilled to be presenting it.

Spiritual minimalism is a term used to describe the musical compositions of a number of late-twentieth-century and early twenty-first century composers of Western classical music. These compositions tend to have simplified musical materials—a strong foundation in functional tonality or modality; simple, repetitive melodies; straightforward, unchanging meters-- compared with the serial, experimental, often extremely complicated styles which had been the prevailing practice in the preceding years. This seeming look backward has been labeled neo-romanticism and post-modernism by some, as it seems to return to the lyricism of the nineteenth century. Most of these composers focus on an explicitly religious orientation, and look to Renaissance and medieval sacred music for inspiration, as well as to the liturgical music of the eastern orthodox churches. Three of these composers-- Arvo Pärt, John Tavener, and Henryk Górecki-- have had remarkable popular success, being featured on CDs which have sold, worldwide, by the millions. Despite being grouped together, these composers work independently and have very distinct styles, and tend to dislike being labeled with the term “spiritual minimalist;” they are by no means a "school" of close-knit associates. Their widely differing nationalities, religious backgrounds, and compositional inspirations make the term problematic; nonetheless, it is in widespread use, perhaps for lack of a better term.

Norwegian composer Knut Nystedt (1915-2014) is the earliest composer to be represented on Chorale’s November concerts. He composed the motet we will sing, Audi, in 1968, as one movement of a larger, orchestrated oratorio, Lucis Creator Optime, and then adapted it for a cappella choir. His name does not usually appear in a listing of minimalist composers—he was very much a regional phenomenon, a Norwegian church musician who listed Aaron Copeland as his principal teacher.

But the evidence at hand—the musical nature of Nystedt’s compositions-- tells an interesting story, and one which for me sheds light on essential characteristics the minimalist composers share. Though predating the seminal figures of this compositional trend by some twenty years, Nystedt clearly pursued many of the same ideals and goals. Like them, he composed primarily choral settings of biblical and liturgical texts, and did so with an ear for sonorous combinations of sounds which would enhance the emotionality of the texts through relatively simple means- short, repeated melodic phrases and motifs, which build and subside through layering techniques which at first glance seem surprisingly simple; cool, traditional harmonic colors; slow-moving and unvarying rhythms. And above all, fidelity to the sacred texts he has chosen-- as a composer for Christian worship, he sought appropriate colors for presenting text to his listeners as emotion and transcendence, rather than as rational explication. He claimed the sacred music of Palestrina as his principle inspiration, but delved deeply into modern techniques of musical expression.

There is something subtly but very clearly “northern” about Nystedt’s music—a plainness, a coolness with interjections of warmth (more cool than warm), a particular combination of light and dark (far more dark than light) which I hear in all of the music we will present in this concert—and which seems an essential characteristic of this minimalist “school,” close-knit or not. In my ears, Audi sounds like the souls of the damned, lost and alone and crying out in space, up with the Northern lights-- a quality I hear as well in Pärt’s music, particularly, and in that of other, far younger composers represented on our program. I hope you will come and hear it—this is undoubtedly some of the best choral music currently being written, and we are thrilled to be presenting it.

Arvo Pärt at 80

Chorale’s November concerts are built around the music of Arvo Pärt, in honor of his 80th birthday. A third of our selections will be by Pärt, the other two thirds by composers associated with him in one way or another.

Chorale’s November concerts are built around the music of Arvo Pärt, in honor of his 80th birthday. A third of our selections will be by Pärt, the other two thirds by composers associated with him in one way or another.

Pärt was born in Estonia in 1935, during the brief window before World War II during which Estonia and the other Baltic countries were sovereign nations, before being taken over, first, by the Nazis, and then by the Soviet Union. The Soviet occupation profoundly impacted his musical development—little news and influence from outside the Soviet Union were allowed into Estonia, and Pärt had to make a lot up as he went along, with the help of illegally obtained tapes and scores, and under constant threat of harassment from the Soviet authorities.

His compositions are generally divided into two periods. His early works demonstrate the influence of Russian composers such as Shostakovich and Prokofiev, but he quickly became interested in Schoenberg and serialism, planting himself firmly in the modernist camp. This brought him to the attention of the Soviet establishment, which banned his works; it also proved to be a creative dead-end for him. Shut down by the authorities, Pärt entered a period of compositional silence, having "reached a position of complete despair in which the composition of music appeared to be the most futile of gestures, and he lacked the musical faith and willpower to write even a single note (Paul Hillier)." During this period he immersed himself in early European music, from Gregorian chant through the development of polyphony in the Renaissance. The music that began to emerge after this period—a date generally set at 1976-- was radically different from what had preceded it. Pärt himself describes the music of this period as tintinnabuli —like the ringing of bells. It is characterized by simple harmonies, outlined triads, and pedal tones, with simple rhythms which tend not to change tempo over the course of a composition. He converted from Lutheranism to Russian Orthodoxy, and began to set Biblical and liturgical texts, with an obvious faith and fervor which once again brought him into conflict with the Soviet regime.

In 1980, after years of struggle over his overt religious and political views, the Soviet regime allowed him to emigrate with his family. He lived first in Vienna, where he took Austrian citizenship, and then relocated to Berlin, in 1981. He returned to Estonia after that country regained its independence, in 1991, and now lives alternately in Berlin and Tallinn.

Chorale will perform a chronological range of Pärt’s a cappella sacred music, beginning with Summa (1977), an austere setting of the Latin Credo which clearly demonstrates the early development of his signature tintinnabular style; Bogoroditse Djevo (1990); Zwei slawische Psalmen (1997); Nunc dimittis (2001); and Da pacem Domine (2004). We don’t intend our concert to be an academic display of Pärt’s development, but I do think listeners will be interested to hear how these works differ from one another, reflecting his growing confidence in his materials, and his growing ease at using these materials to express the emotional depth of his religious faith, moving from the strictly abstract toward something which transcends technique and procedure, and manages to fill a deep human need in those who experience his music.

Ready... Set... RETREAT!

Each autumn, close to the beginning of the new season’s rehearsal period, Chorale holds a Saturday retreat.

Each autumn, close to the beginning of the new season’s rehearsal period, Chorale holds a Saturday retreat, at which we eat three times, rehearse for about five hours, and have a chance to interact with one another, extensively and extra-musically. For the past three seasons, we have retreated to Ellis Avenue Church, a reconfigured mansion in the Kenwood neighborhood, just north of Hyde Park. The building has a room big enough to hold all of us, a decent piano, a large kitchen, a spacious yard, and a wonderful, open front porch and steps, where most of our non-musical time is spent.

The food, the drinks, the dishes and utensils, the charcoal, are provided both by Chorale management, and by Chorale members. We always have more than we consume—our members are generous. Coffee, bagels, and donuts for breakfast; pizza or sandwiches for lunch; bratwurst and potluck items for supper. While Chorale rehearses, our managing director, Megan Balderston, and our board president, Angela Grimes, set things out for the various meals, then clear them away to make room for the next repast. At the end of the day, folks pack up their leftovers, their coolers, their dishes and utensils, and head home.

Frequently, we have guest observers, who show up in the afternoon and sit in on our rehearsal, watching and listening as we work, and then join us for supper. At various points during rehearsal, we break off singing, and Megan, Angela, and I address the choir about our coming season, as well as explain various long-term policies and procedures, of which new members may be unaware—and of which everyone should be reminded.

This retreat, coming as it does between two consecutive Wednesday rehearsals, really jump-starts our learning of new music. With only two or three days between rehearsals, the singers forget very little between one Wednesday and the next, and end up much further along with concert preparation, by the second Wednesday, than the hours of rehearsal alone would suggest. And—the choral disciplines to which we subscribe, become more familiar and deep-seated, with concentrated exposure. Our sound, our phrasing, our onsets and cutoffs, all improve immensely over the course of this one week.

A word about the bratwurst. I have always provided bratwurst for my choirs, ever since I began conducting at the University of Chicago, back in 1984. I used to order it—first, from Tuvey’s Meat and Music, in Watertown, Minnesota, back when my family farmed near there; then, after I moved to the University of Virginia, through a German restaurant in Charlottesville. About the time I returned to Chicago and founded Chorale, it occurred to me that I could save a lot of money, and have more fun, if I just made it myself. I had grown up in a sausage-making family, and knew it was possible. I experimented around with recipes and procedures, and finally came up with what I now make. There is always plenty. This year, a former member of my other ensemble, Chicago Men's A Cappella, Adam Gillette, will start the fires and do some grilling while we rehearse—so that the brats will be ready, fresh and hot, when we quit rehearsing.

Sausage is like choirs: one takes many disparate ingredients, carefully and artfully combines them, stuffs them into something that gives them structure, and comes up with a product that is ever so much better than the sum of its parts. For me, a perfect metaphor for my role as conductor.

Kit Bridges, Chorale's Rehearsal Accompanist

A good rehearsal accompanist can be essential to a choir’s success.

A good rehearsal accompanist can be essential to a choir’s success, especially a larger choir, like Chorale. If the conductor is tied to the piano, constantly giving pitches, playing parts, helping with tricky passages, he cannot focus on his singers—their sound, their vocalism, their ensemble production. And a mediocre to bad accompanist—one that lacks personally artistry, that doesn’t listen to the conductor or the singers, is not attuned to the conductor‘s preferences and needs, does not anticipate the conductor’s ideas and techniques, and does not mirror these things in his playing-- is even worse than no accompanist at all. If an accompanist slows the rehearsal down, it is better for the conductor to struggle at the keyboard himself, bad as that is; at least he can keep the pacing of the rehearsal up.

A good rehearsal accompanist can be essential to a choir’s success, especially a larger choir, like Chorale. If the conductor is tied to the piano, constantly giving pitches, playing parts, helping with tricky passages, he cannot focus on his singers—their sound, their vocalism, their ensemble production. And a mediocre to bad accompanist—one that lacks personally artistry, that doesn’t listen to the conductor or the singers, is not attuned to the conductor‘s preferences and needs, does not anticipate the conductor’s ideas and techniques, and does not mirror these things in his playing-- is even worse than no accompanist at all. If an accompanist slows the rehearsal down, it is better for the conductor to struggle at the keyboard himself, bad as that is; at least he can keep the pacing of the rehearsal up.

A good accompanist is more than a good pianist. He is even more than a good musician. He is completely attuned to the needs of the conductor and the group, and uses his energies and talents to help the choir sound better, and to help the conductor do a better job. His work serves as the rehearsal’s foundation.

Chorale is blessed with such an accompanist.

I first met Kit Bridges when he and I were grad students at Northwestern University. He accompanied the studio of Norman Gulbrandsen, which included most of the best singers at the school—and he played like a god. He brought technique, sensitivity, artistry, to what can be a very boring and perfunctory position, and made his singers sound like polished artists, even if they were too thick to know he was doing it. I started out in a different studio, with a different accompanist; one of the principle reasons I finally switched to Gulbrandsen, was to work with Kit. He exemplified for me the kind of collaborative artistry I heard in the recordings of Dalton Baldwin and Gerald Moore—and I wanted that sort of a musical experience, more than anything else. That was many years ago, now; but I have been privileged to work with Kit in one capacity or another ever since, and was thrilled past my wildest dreams when, three years ago, he agreed to serve as Chorale’s regular accompanist.

It is a little like hitching a thoroughbred to a plow—why should someone with Kit’s abilities, be sitting at a piano bench, giving pitches to a choir? But he even gives pitches artfully! And the grace with which he plays our warm ups, pulls more out of the unwitting choir, than any amount of verbiage from me can. Besides, it fills me with such security and confidence to have him there—he can hear what is going wrong when I can’t, can pinpoint problem areas and fix them, ever so quietly and unobtrusively, while I am struggling with other issues.

Most members of Chorale have little idea of what Kit does during the rest of the week—the classes he teaches, the singers he coaches, the recitals he plays, the major auditions he accompanies. They take him gloriously for granted. But I know that we have the very best, right there in the room with us-- and that he helps Chorale be the very best we can be.

Our first rehearsal of the season

Choirs work better when they know and like each other—and food always helps.