Palestrina: The "Savior of Music"?

Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

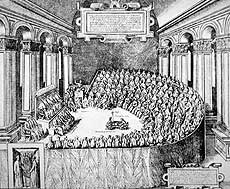

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the  increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

It seems unlikely that the Pope Marcellus Mass was composed with the intent of saving music, or even that Palestrina’s name, career, and music came up in the Council’s discussions. No documentation exists to support such a role for him. Most likely, he was a career church musician who was willing to make a few minor adjustments to fit certain requirements because it was the sensible thing to do. Nonetheless, beginning almost immediately in 1564, Palestrina became “the savior of music,” and remained so through the later twentieth century. The Roman Catholic Church presented his compositional style as a model for good church music, and generations of music students studied his works, particularly this mass, as an example of what they should understand and emulate. Giuseppe Verdi said of the composer, “He is the real king of sacred music, and the Eternal Father of Italian music.” In James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses (1934), Joyce's friend Frank Budgen quotes him as saying "that in writing this Mass, Palestrina saved music for the church." Palestrina’s magisterial image was set in stone.

Chorale is finding the Pope Marcellus Mass to be a very rewarding project. The music is lovely, soothing, uplifting; it flows so naturally and effortlessly, one would imagine its composition to have been easy for the composer. The more deeply we delve into it, however, the more we discover Palestrina’s craft and skill, and the genius of his contrapuntal writing. I discover, myself, a similarity to Mozart’s music: a gracious, pleasing, untroubled surface, a kind of abstract perfection: but so difficult to describe and define, once one is inside it. It demands extraordinary skill and grace in performance; and yields, on its own, incredible richness and satisfaction. Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.

Adventures in Programming

Chorale’s current project features some of the most unusual programming we have ever put out there.

Chorale’s current project features some of the most unusual programming we have ever put out there. We have paired two major a cappella works which, on the surface, bear little resemblance to one another: the magisterial Missa Papae Marcelli by G.P. da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594), and The Peaceable Kingdom by Randall Thompson (1899-1984). The two works are approximately the same length, and require similar vocal forces; and they are both pieces with which most choral musicians are broadly familiar, but which few of them have actually sung. The Mass is cited in music history texts as the pinnacle of Palestrina’s writing, reflecting the compositional elements which influenced generations of church musicians which followed him; and Randall Thompson, the “dean of American composers,” has been afforded a similar status by twentieth century American musical critics. Both men, and their works, are revered, hoary monuments, referenced but somehow no longer current. Our goal, this spring, is to encounter them where the rubber hits the road, in performance, and rediscover what made them so important in the first place.

The League of Composers commissioned Thompson in 1935 to write a major work for unaccompanied chorus. He chose as his point of departure a primitivist painting entitled “The Peaceable Kingdom” by Edward Hicks (1780-1849), “the preaching Quaker of Pennsylvania.” It illustrates Isaiah XI:6-9:

The League of Composers commissioned Thompson in 1935 to write a major work for unaccompanied chorus. He chose as his point of departure a primitivist painting entitled “The Peaceable Kingdom” by Edward Hicks (1780-1849), “the preaching Quaker of Pennsylvania.” It illustrates Isaiah XI:6-9:

The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them. And the cow and the bear shall feed; their young ones shall lie down together: and the lion shall eat straw like the ox. And the suckling child shall play on the hole of the asp, and the weaned child shall put his hand on the cockatrice’ den. They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain: for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea.

In the middle distance, William Penn negotiates with the Indians by the shore of the Delaware River.

Inspired both by the painting and by the passage it illustrates, Thompson studied the book of Isaiah and selected eight passages referencing themes of peace and violence, and of good versus evil. In general, Thompson’s compositional style is conservative-- he prefers triadic harmonies, melodic sequences, imitative passages, Renaissance modality, and Venetian polychoral texture—but the stark contrasts in the Isaiah text inspire vivid, imaginative text-setting, appropriately dissonant harmonic passages, and large sections of recitative-like declamation, alternating with luscious, lyrical sections. He is able to express a variety of moods effectively, keeping interest and anticipation high. And the composer’s ordering of his text sets up a successfully dramatic narrative trajectory-- the work as a whole has a satisfying shape and arch, with a reassuring climax. I have, myself, had the opportunity to sing quite a lot of Thompson’s choral music over the years, and find this to be the most successful and satisfying of his major works—and also the freshest and most creative, considering the passage of years since he was actively composing. “Primitivism,” with Thompson as well as with Hicks, refers to conception, rather than execution; both men have the sophistication and skill to accomplish major works, but are freed from the rigidity of their respective disciplines by Isaiah’s prophetic vision and language. Chorale and I are finding this to be a fresh, intriguing piece to work on, quite different from anything else we have ever performed.

Meet Chorale's B Minor Soloists

Chicago Chorale has a roster of outstanding soloists for its upcoming performance of the Mass in B Minor, March 26.

Chicago Chorale has a roster of outstanding soloists for its upcoming performance of the Mass in B Minor, March 26:

Michigan native Chelsea Shephard, soprano, recently gave an “exquisite” NYC recital debut, garnering praise for her “beautiful, lyric instrument” and “flawless legato” (Opera News). This season includes Ms. Shephard’s Carnegie Hall debut with Cecilia Chorus of New York for a World Premiere by Syrian composer Zaid Jabri and Brahms Requiem, joining Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster for Das Rheingold, and return engagements with the Madison Bach Musicians. Past season highlights include: Beth/Little Women, Calisto/La Calisto, Pamina/Die Zauberflöte, Susanna/Le nozze di Figaro, Lauretta/Gianni Schicchi, Lisa/The Land of Smiles, Emily Webb/Our Town, and Poppea/L’incoronazione di Poppea with companies such as Madison Opera, Opera Grand Rapids, Haymarket Opera Company, and Caramoor International Music Festival. Ms. Shephard’s accolades include: Education Grant/Metropolitan Opera National Council (2016), Finalist/Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ryan Opera Center (2015), First Place/Madison Early Music Festival Handel Aria Competition (2014), and Finalist/Jensen Foundation Competition in NYC (2014).

Michigan native Chelsea Shephard, soprano, recently gave an “exquisite” NYC recital debut, garnering praise for her “beautiful, lyric instrument” and “flawless legato” (Opera News). This season includes Ms. Shephard’s Carnegie Hall debut with Cecilia Chorus of New York for a World Premiere by Syrian composer Zaid Jabri and Brahms Requiem, joining Lyric Opera of Chicago’s roster for Das Rheingold, and return engagements with the Madison Bach Musicians. Past season highlights include: Beth/Little Women, Calisto/La Calisto, Pamina/Die Zauberflöte, Susanna/Le nozze di Figaro, Lauretta/Gianni Schicchi, Lisa/The Land of Smiles, Emily Webb/Our Town, and Poppea/L’incoronazione di Poppea with companies such as Madison Opera, Opera Grand Rapids, Haymarket Opera Company, and Caramoor International Music Festival. Ms. Shephard’s accolades include: Education Grant/Metropolitan Opera National Council (2016), Finalist/Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Ryan Opera Center (2015), First Place/Madison Early Music Festival Handel Aria Competition (2014), and Finalist/Jensen Foundation Competition in NYC (2014).

Chelsea holds degrees from DePaul University and Rice University.

Mezzo-soprano Angela Young Smucker has earned praise for her “luscious” voice (Chicago Tribune) and "powerful stage presence" (The Plain Dealer). Her performances in concert, stage, and chamber works have made her a highly versatile and sought-after artist. Highlights of the 2016-17 season include performances with Haymarket Opera Company, Bach Collegium San Diego, Chicago A Cappella, Seraphic Fire, and newly-founded Third Coast Baroque. Ms. Smucker has also been a featured soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Music of the Baroque, Oregon Bach Festival, Bella Voce, and Les Délices. Radio and television appearances include Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, WFMT’s Impromptu and Live from WFMT, and WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Mezzo-soprano Angela Young Smucker has earned praise for her “luscious” voice (Chicago Tribune) and "powerful stage presence" (The Plain Dealer). Her performances in concert, stage, and chamber works have made her a highly versatile and sought-after artist. Highlights of the 2016-17 season include performances with Haymarket Opera Company, Bach Collegium San Diego, Chicago A Cappella, Seraphic Fire, and newly-founded Third Coast Baroque. Ms. Smucker has also been a featured soloist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Music of the Baroque, Oregon Bach Festival, Bella Voce, and Les Délices. Radio and television appearances include Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, WFMT’s Impromptu and Live from WFMT, and WTTW’s Chicago Tonight.

Currently pursuing her doctoral studies at Northwestern University, Ms. Smucker holds degrees from the University of Minnesota and Valparaiso University – where she also served as instructor of voice for seven years. She is a NATS Intern Program alumna, former Virginia Best Adams Fellow (Carmel Bach Festival), and serves as Executive Director of Third Coast Baroque.

A "superb vocal soloist" (The Washington Post) possessing a "sweetly soaring tenor" (The Dallas Morning News) of "impressive clarity and color" (The New York Times), tenor Steven Soph performs throughout North America and Europe. Recent seasons' highlights include appearances with The Cleveland Orchestra in an all-Handel program led by Ton Koopman; the New World Symphony and Seraphic Fire in Reich's Desert Music; Symphony Orchestra Augusta in Bach's B minor Mass; San Diego's Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra in Mozart's "Orphanage" Mass and Mass in C minor; Voices of Ascension in Bach's Magnificat and St. Matthew Passion; the Master Chorale of South Florida in Mozart's Requiem and Haydn's Lord Nelson Mass; Colorado Bach Ensemble in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion; Texas Choral Consort in Haydn's Creation; and the Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra in Handel's Messiah.

A "superb vocal soloist" (The Washington Post) possessing a "sweetly soaring tenor" (The Dallas Morning News) of "impressive clarity and color" (The New York Times), tenor Steven Soph performs throughout North America and Europe. Recent seasons' highlights include appearances with The Cleveland Orchestra in an all-Handel program led by Ton Koopman; the New World Symphony and Seraphic Fire in Reich's Desert Music; Symphony Orchestra Augusta in Bach's B minor Mass; San Diego's Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra in Mozart's "Orphanage" Mass and Mass in C minor; Voices of Ascension in Bach's Magnificat and St. Matthew Passion; the Master Chorale of South Florida in Mozart's Requiem and Haydn's Lord Nelson Mass; Colorado Bach Ensemble in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion; Texas Choral Consort in Haydn's Creation; and the Cheyenne Symphony Orchestra in Handel's Messiah.

Described as an Evangelist “first-class across the board,” (Chicago Classical Review) Steven performed with the Chicago Chorale in Bach's St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion, at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion and with the Concord Chorale in the St. John Passion.

Steven holds degrees from the University of North Texas and Yale School of Music, where he studied with renowned tenor James Taylor.

Ryan de Ryke (baritone) is an artist whose versatility and unique musical presence have made him increasingly in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. He has performed at many of the leading international music festivals including the Aldeburgh and Edinburgh Festivals in the UK and the summer festival at Aix-en-Provence in France garnering significant acclaim as both a recitalist and singing actor.

Ryan de Ryke (baritone) is an artist whose versatility and unique musical presence have made him increasingly in demand on both sides of the Atlantic. He has performed at many of the leading international music festivals including the Aldeburgh and Edinburgh Festivals in the UK and the summer festival at Aix-en-Provence in France garnering significant acclaim as both a recitalist and singing actor.

Ryan studied at the Peabody Conservatory with John Shirley Quirk, the Royal Academy of Music in London with Ian Partridge, and at the National Conservatory of Luxembourg with Georges Backes. His is also an alumnus of the Britten-Pears Institute in the UK and the Schubert Institute in Austria where he worked with great artists of the song world such as Elly Ameling, Wolfgang Holzmair, Julius Drake, Rudolf Jansen, and Helmut Deutsch.

Ryan can often be seen collaborating with Haymarket Opera Chicago where he performed title role in Telemann’s Pimpinone, voted one of Chicago’s top 5 performances of 2013, and last season played the role of Sancho Panza in Don Quichotte.

My Third Time Around

How will I experience my fourth B Minor Mass performance? I don’t know, but I hope I’m lucky enough to find out.

Guest Blog by Dan Bertsche, who has sung tenor with Chicago Chorale since 2003, and currently serves as Secretary on Chicago Chorale’s Board of Directors.

Guest Blog by Dan Bertsche, who has sung tenor with Chicago Chorale since 2003, and currently serves as Secretary on Chicago Chorale’s Board of Directors.

I remember approaching my first Bach B Minor Mass, in 2006, something like Sir Edmund Hillary must have approached his ascent of Mount Everest. This work is so difficult and monumental, and the only path I saw to a successful performance was through hard work, by developing lung capacity, stamina, and endurance—and by staying hydrated. Rehearsals were exhilarating, but at the same time fatiguing. After that first performance, the profound satisfaction I felt was coupled with equally profound exhaustion—both physical and vocal. “I came, I sang, I conquered. Now I want to sleep.”

My second B Minor Mass—six years ago—felt quite different. My familiarity with the score, coupled with the fact that everything was pitched at a=415 (a half-step down), allowed more space for appreciating what makes this work so very great in the first place. This was no longer a forced march to the mountaintop; but a walk through a garden of wonders. I recall marveling at the complexity and perfection of the Kyrie I; admiring the skill with which the cantus firmus emerges from the secondary material in Confiteor (still my favorite movement of the entire work); and being astounded by how there could be so many 16th notes in so many voices and instruments in the Cum Sancto Spiritu, and that the movement could still come across with such clarity and coherence. During my second B Minor Mass, I learned to appreciate Bach as “master composer,” rather than as “master obstacle-course builder.”

This year, some of my reverence for Bach’s compositional skill has been replaced by more general gratitude for this monumental work. Had Bach not bothered to compose it, or had it been lost to history, right now Chicago Chorale would frankly be preparing to perform a lesser piece. But because of this gift to posterity, fifty-five ordinary people are experiencing the magic that happens when engaging this extraordinary work. And as we strive to bring out the very best in the B Minor Mass, the B Minor Mass is bringing out the very best in us. Our collective vocal production is more healthy and vigorous; we are listening better within and across sections; we are sitting up a bit straighter; and we are more honest with ourselves about which spots need individual attention. On some level, Chorale members know that a great performance of a mediocre work still yields a mediocre result. So we are grateful that Bach has given us a masterpiece with a nearly unlimited performance “upside potential,” and we are pulling together to get as close to that ceiling as possible.

This time around, I am also struck by how much fun rehearsals are, by how much I look forward to them, and by the fact that I leave each rehearsal more energized than when I arrive.

How will I experience my fourth B Minor Mass performance? I don’t know, but I hope I’m lucky enough to find out.

Chorale's Choices

No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

I have written largely about the historical/musicological aspects of presenting Bach’s Mass in B Minor, over the past weeks. Such a focus is inevitable: the score is enormous, complex, surrounded and influenced by competing traditions; a conductor is forced to make decisions about every page, and to coordinate these many decisions in order to come up with a coherent whole. No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

In the performance history of the work, enormous choruses, numbering in the hundreds, have sung, and continue to sing, the Mass in B Minor, though the general trend has been toward smaller forces– on occasion, just one singer per part. Chorale is fifty-six singers for this concert-- by no means a symphony chorus, but larger than the professional early music ensembles which present the most cutting edge versions of the work. We could have chosen to bypass the work altogether, in acknowledgment of historical correctness– but then we would be deprived of the glorious experience of learning and performing the work, and our audience would be deprived of the opportunity to hear it. So we choose to sing it, and to devote tremendous effort toward lightening our sound and articulation, while making the most of our full sound where it is needed and welcome.

I have written largely about the historical/musicological aspects of presenting Bach’s Mass in B Minor, over the past weeks. Such a focus is inevitable: the score is enormous, complex, surrounded and influenced by competing traditions; a conductor is forced to make decisions about every page, and to coordinate these many decisions in order to come up with a coherent whole. No work is more studied or more commented upon; no work excites more controversy. I have to be able to defend the choices I make. And I have to satisfy my own need to express a personal vision: Chorale is presenting a work of art, not a music history lecture about a work of art.

In the performance history of the work, enormous choruses, numbering in the hundreds, have sung, and continue to sing, the Mass in B Minor, though the general trend has been toward smaller forces– on occasion, just one singer per part. Chorale is fifty-six singers for this concert-- by no means a symphony chorus, but larger than the professional early music ensembles which present the most cutting edge versions of the work. We could have chosen to bypass the work altogether, in acknowledgment of historical correctness– but then we would be deprived of the glorious experience of learning and performing the work, and our audience would be deprived of the opportunity to hear it. So we choose to sing it, and to devote tremendous effort toward lightening our sound and articulation, while making the most of our full sound where it is needed and welcome.

Frequently, even when larger groups sing it, a smaller group, termed concertists, will introduce many of the movements, will sing particularly exposed passages as solos, will even sing the more intimate movements entirely on their own. Sometimes, these concertists will be members of the choir; alternatively, they may be the soloists who also sing the aria and duet movements. This trend toward ripienist/concertist texture is supported by the scholarly literature. Chorale chooses to forego the ripienist/concertist procedure. It could have been interesting and appropriate for our forces, but our singers want to experience all of the music, each note, as an amateur event—an act of love. As Robert Shaw said—music, like sex, is too good to be left to the professionals. Again, this forces us to be more careful in our control of texture and dynamics than we would be if those issues were resolved through controlling the size of the forces.

Chorale chooses to sing the Latin text with a German pronunciation. Most ensembles use the more common Italianate pronunciation, and have good results; and recent research indicates that the German pronunciation Chorale uses, based on modern German, is not necessarily the pronunciation Bach used or intended. So we can’t defend our choice on a secure, scholarly basis. But our choice does suggest the music’s German background. And I agree with Helmuth Rilling’s contention that German consonants articulate more clearly than Italian, while German vowels narrow and clarify the vocal line, even for an entire section of singers, lending greater definition to Bach’s remarkably complex counterpoint. This is particularly necessary with a group of our size: clarity of pitch and line is far more important, in this music, than the beautiful, Italianate production of individual voices in the ensemble, which can actually work against an accurate presentation of Bach’s musical ideas.

We choose to present the Mass at Rockefeller Chapel, on the campus of The University of Chicago, because the building’s size and grandeur reflect Bach’s music more accurately than other spaces available to us. The Hyde Park community, which surrounds the Chapel, represents, in a purer form than other Chicago neighborhoods, the combination of scholarship, idealism, and high culture which can support concerts like this. A high percentage of Chorale’s regular audience are Hyde Park residents, and they often express appreciation for the level of Chorale’s striving and seriousness of intent. And from a purely monetary point of view, Rockefeller Chapel seats a sufficient number of listeners that, if we sell tickets effectively, we can cover a significant proportion of our production costs (which are mind-boggling) with door receipts.

We choose to present the Mass at Rockefeller Chapel, on the campus of The University of Chicago, because the building’s size and grandeur reflect Bach’s music more accurately than other spaces available to us. The Hyde Park community, which surrounds the Chapel, represents, in a purer form than other Chicago neighborhoods, the combination of scholarship, idealism, and high culture which can support concerts like this. A high percentage of Chorale’s regular audience are Hyde Park residents, and they often express appreciation for the level of Chorale’s striving and seriousness of intent. And from a purely monetary point of view, Rockefeller Chapel seats a sufficient number of listeners that, if we sell tickets effectively, we can cover a significant proportion of our production costs (which are mind-boggling) with door receipts.

Our concert is in one month. Sunday, March 26, 3 p.m.

We have rehearsed, and I have written about the experience, since the middle of December. The writing has focused my study, my listening, my thinking about the work; it has been a significant and helpful discipline for me. I hope you will come to our performance; and I hope you will spread the word, and bring your friends. I’m a believer; I am convinced that Bach’s Mass in B minor truly is “the greatest artwork of all times and all people,” and I’d like to show you why.

Composing the Mass in B Minor

Bach effectively spent his entire career composing Mass in B Minor— it consists of complete movements, and fragments, from throughout his compositional life, recomposed, reworded, reconfigured, stitched together with newly composed music.

Bach effectively spent his entire career composing Mass in B Minor— it consists of complete movements, and fragments, from throughout his compositional life, recomposed, reworded, reconfigured, stitched together with newly composed music — Bach scholar Christoph Wolff calls the Mass a “specimen book,” a collection of examples of genres and techniques which covers not only Bach’s personal history, but the history of Western music. In the process of compiling this music into a single great work, at the end of his life, Bach seems intent on summing up that history and presenting his summation to his successors. The Sanctus was first performed in 1724; movement 4 of the Credo, Et incarnatus est, thought to be the last music he composed, dictated to an assistant because Bach himself was blind, was completed in 1750. The remaining music reflects Bach’s experience during the intervening 26 years. Plagiarism and parody were not a dirty words in Bach’s time. Bach, and his colleagues, had immense responsibilities in the preparation and performance of music for the theater, the court, the church– and their success depended on getting it all done, rather than on satisfying a theoretical mandate that they be original. They were free, even expected, to build upon the successes of others, to copy and share one another’s scores, to use procedures and formulas, melodies and bass lines, that had worked well for other composers, and alter them to suit their own tastes and circumstances, even to change their own products and procedures over time as needs and tastes changed. Music was a living, volatile consumer product, constantly evolving to meet demand. Creativity reflected one’s ability to arrange the materials at hand, as well as to invent new materials. Bach borrowed freely and happily from other composers, as well as from himself, both because this enriched his product, and because it allowed him to keep up with his workload. It is inconceivable that Bach could have accomplished all he did in his lifetime, were he under pressure to stay away from the intellectual property of others.

An extraordinary amount of Bach scholarship over the past century has focused on sleuthing out the sources behind Bach’s music, and in preparing new and better editions of his music, based on this detective work. And while the scholars involved in this work frequently disagree with one another, as a group they persistently push the envelope, and contribute to our knowledge of the composer and his methods. Between them, these researchers have determined that very little of what is now called Mass in B Minor was freshly composed for the work– perhaps as few as four or five movements. Bach selected music for the remaining movements from cantatas which he had composed throughout his career. Scholars agree that he seems to have chosen what he thought was his best work, music which would suit the character of the Mass, and would reflect accurately the new, Latin texts. He transposed some movements to new keys, in keeping with the overall key structure of the new work; he adapted phrase structure to fit the alternate texts; he eliminated instrumental introductions and interludes, to move the dramatic action forward more efficiently; and he composed new movements, and sections of movements, where he needed them to complete the work.

Though the Ordinary of the Roman Catholic Mass consists of only five movements—Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus/Benedictus/Osanna, and Agnus Dei—Bach divides the text and music of his Mass in B Minor into twenty-three separate movements. With the exception of the Gratias/Dona nobis movements, and the repeat of the Osanna, each movement has different music.

Let’s consider movements 3-6 of the Credo portion: Et in unum Dominum, Et incarnatus est, Crucifixus, and Et resurrexit. Scholars agree, based on internal evidence, that Bach adapted the duet Et in unum from an earlier composition, though that earlier work is lost. The close imitation between the two voices is ideally suited to a love duet, probably from a secular work, and adapts easily to a text which expresses the consubstantiality of the Father and the Son. In his original version of the Mass, Bach set the entire text of movements three and four within this one movement. It was only in the final months of his life (determined, again, on the basis of internal evidence) that he decided he needed a separate movement to set the words “And was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man.” So he kept the music for movement 3 intact, had the soloists repeat earlier words, and composed a completely new movement — one of the few freshly-composed movements in the Mass, and one of Bach’s final compositional efforts. In so doing, he created a numerical symmetry which the Credo had previously lacked, placing the Crucifixus exactly at the center of this discrete section, as well as at the center of all of the Mass movements which lie between the identical music of the Gratias and the Dona nobis movements. It is an amazing engineering feat, adding internal structure for the connoisseur and first time listener alike.

Bach adapted the Crucifixus movement from his cantata BWV 12, where it has the words Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, lamentation,worry, apprehension). Bach scholar John Butt hypothesizes that Bach could have adapted even this early cantata movement (1714) from a similar movement by Vivaldi (Piango, gemo, sospiro e peno), but goes on to say that such laments were standard literary forms, and that, together with its descending bass line, is such a standard form that it would be stretching things to suggest that Bach did anything other than compose his own version of a common form. More interesting are the final four bars of the Crucifixus; Bach added these to the music he borrowed from himself, and with them modulates to G Major (setting up the D Major of the following Et resurrexit) and brings the choral forces down to the lowest pitches they sing in the entire Mass, representing the lowering of Christ’s body into the sepulchre. The following movement, Et resurrexit, explodes out of this depth with no instrumental introduction—voices and instruments enter with a complete change of affect, in a fanfare-like, rising triad. Scholars assume that this movement, as well, is adapted from an earlier, secular cantata—possibly the lost birthday cantata for August I, BWV Anh. 9. In adapting it, Bach dropped the opening instrumental introduction, which would have slowed down the drama of Easter morning, but included other instrumental interludes, which have a euphoric, dance-like character and seem to suggest heaven and earth rejoicing.

Bach adapted the Crucifixus movement from his cantata BWV 12, where it has the words Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen (Weeping, lamentation,worry, apprehension). Bach scholar John Butt hypothesizes that Bach could have adapted even this early cantata movement (1714) from a similar movement by Vivaldi (Piango, gemo, sospiro e peno), but goes on to say that such laments were standard literary forms, and that, together with its descending bass line, is such a standard form that it would be stretching things to suggest that Bach did anything other than compose his own version of a common form. More interesting are the final four bars of the Crucifixus; Bach added these to the music he borrowed from himself, and with them modulates to G Major (setting up the D Major of the following Et resurrexit) and brings the choral forces down to the lowest pitches they sing in the entire Mass, representing the lowering of Christ’s body into the sepulchre. The following movement, Et resurrexit, explodes out of this depth with no instrumental introduction—voices and instruments enter with a complete change of affect, in a fanfare-like, rising triad. Scholars assume that this movement, as well, is adapted from an earlier, secular cantata—possibly the lost birthday cantata for August I, BWV Anh. 9. In adapting it, Bach dropped the opening instrumental introduction, which would have slowed down the drama of Easter morning, but included other instrumental interludes, which have a euphoric, dance-like character and seem to suggest heaven and earth rejoicing.

In his handbook for the study of the Mass in B Minor, John Butt recounts the experience of early Bach scholar Julius Rietz, who wrote the first published study of the sources of the Mass in 1857: “Reitz shows himself to have been a meticulous scholar, who even made enquiries into the fate of Bach’s first set of parts of the Sanctus, copied in 1724 and loaned to Graf Sporck. The inheritors of the estate informed Rietz that many manuscripts had been given to the gardeners to wrap around trees. One can barely dare to envisage what similar fates befell other manuscripts from Bach’s circle.” I expect Bach would not have been surprised by this; the archives and libraries of our modern world would probably astound him. Christoff Wolff suggests that one of the principle motivations behind Bach’s compilation of the Mass was his assumption that the thousands of pages of his cantata cycles would not be preserved—that they were too specific to their own time, location, and purpose to be of any use once he was gone, and that the only way he could preserve the best of his work was to use it for a Latin Mass, which would have a better chance of being saved and recognized in the future. My years of participation in the Oregon Bach Festival have given me the opportunity to sing and study many of Bach’s surviving cantatas, but I am lucky to have had this experience—most performers know only a handful of them, and most listeners don’t know them at all. So from our viewpoint, Bach had it right—his Mass enables us to know not only what he was able to preserve, but also the dimensions of our loss.

I read somewhere that Bach shows us what it means to be God, Mozart shows us what it means to be human, and Beethoven shows us what it means to be Beethoven. I agree with the Bach part, at least. Beyond the notes, the rhythms, the historically informed performance practices, one experiences his works as living beings, as manifestations of God in the world. They demonstrate that we humans are better than we think we are, better than much of what we see around us, and convince me that it is always worth it to keep moving ahead, not just out of habit, but because we, like Bach, are capable of holy things.

Chicago Chorale and Historically Informed Performance Practice

Bach was not only a genius; he was a practical, practicing musician. Knowing what he heard, and how he did it, can only improve our performances of his work.

I began attending Oberlin Conservatory’s Baroque Performance Institute in 1978, and continued attending for about eight summer sessions following that. I first learned of the Institute through Ken Slowik, a Chicago cellist and early music specialist, who suggested that my vocal characteristics and musicological curiosity might make me a good candidate for BPI-- especially since Baroque expert Max Van Egmond was joining the faculty that summer. I listened to some of Max’s recordings, recognized a kindred spirit, and decided to take the plunge. The experience was revelatory for me: prior to that, I had never even heard of Baroque pitch, of gut strings, of wooden traverso flutes, of viols, of inégale rhythm. An entirely new world opened for my consideration, and I ate it up, eagerly and hungrily. Max was an ideal teacher and mentor for me, and I sang as often as I could, in lessons, master cases, and concerts; and I observed instrumentalists when I was not singing. BPI was all about performance; scholars and theorists attended, lectured, and added their insights, but the focus was on performing, day and night. I had never loved any musical immersion so much, in my life.

And then, when BPI was over, I would return to my job, conducting choirs and teaching voice, first at Luther College, later at The University of Chicago—and I would have a hard time integrating my BPI experience with my actual day job. One year Ken invited me to sing with the Smithsonian Chamber Players (he was by this time their music director) in Washington, for a performance of Charpentier’s Les Arts Florissants , complete with dance, masks, authentic instruments from the Smithsonian collection—we were so authentic, we even lighted the performance with candles in metal reflectors. The other singers were recognized professionals in the early music field, who did this sort of thing on a regular basis; for me, it was a brief interlude, a vacation, from my teaching. The contrast struck me forcibly, and I withdrew from involvement in early music performance from that point on—I could not see any further value in doing it part way, and I did not want to give up my actual professional life. I enjoyed my students, my choirs, and could not see how this hobby of mine was contributing anything to the health of my program.

I began attending Oberlin Conservatory’s Baroque Performance Institute in 1978, and continued attending for about eight summer sessions following that. I first learned of the Institute through Ken Slowik, a Chicago cellist and early music specialist, who suggested that my vocal characteristics and musicological curiosity might make me a good candidate for BPI-- especially since Baroque expert Max Van Egmond was joining the faculty that summer. I listened to some of Max’s recordings, recognized a kindred spirit, and decided to take the plunge. The experience was revelatory for me: prior to that, I had never even heard of Baroque pitch, of gut strings, of wooden traverso flutes, of viols, of inégale rhythm. An entirely new world opened for my consideration, and I ate it up, eagerly and hungrily. Max was an ideal teacher and mentor for me, and I sang as often as I could, in lessons, master cases, and concerts; and I observed instrumentalists when I was not singing. BPI was all about performance; scholars and theorists attended, lectured, and added their insights, but the focus was on performing, day and night. I had never loved any musical immersion so much, in my life.

And then, when BPI was over, I would return to my job, conducting choirs and teaching voice, first at Luther College, later at The University of Chicago—and I would have a hard time integrating my BPI experience with my actual day job. One year Ken invited me to sing with the Smithsonian Chamber Players (he was by this time their music director) in Washington, for a performance of Charpentier’s Les Arts Florissants , complete with dance, masks, authentic instruments from the Smithsonian collection—we were so authentic, we even lighted the performance with candles in metal reflectors. The other singers were recognized professionals in the early music field, who did this sort of thing on a regular basis; for me, it was a brief interlude, a vacation, from my teaching. The contrast struck me forcibly, and I withdrew from involvement in early music performance from that point on—I could not see any further value in doing it part way, and I did not want to give up my actual professional life. I enjoyed my students, my choirs, and could not see how this hobby of mine was contributing anything to the health of my program.

My succeeding summers were spent, first, at the Nice Conservatory, singing art songs with Gérard Souzay and Dalton Baldwin; then several years with the Robert Shaw Festival Singers; and, finally, ten summers with Helmuth Rilling at the Oregon Bach Festival. All of it was good and worthwhile and stimulating, and contributed to my professional competence.

What goes around, comes around. The bug that bit me back at Oberlin did not die; it just invaded the rest of my music making. Working with both Mr. Shaw and Mr. Rilling, I found myself observing and questioning what they were doing, comparing it to my BPI experience, wondering how it was related, how it could be different, and how I could do things differently, myself, with my own ensembles. During Chorale’s second season, already, we presented the first half of J.S. Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, and we have been programming major Baroque works, primarily Bach’s, ever since. With each successive concert, I introduce more HIPP elements, try more techniques I remember from my Oberlin experiences, require a more “baroque” sound from both the players and the singers, hire more appropriate soloists. Obviously, we do not do museum-quality reproductions of performances that Bach himself led or heard: we do not have his performance space, his highly trained 16-year old prepubescent boys, or his audience. We prepare performances for the buildings we have, with the singers we have, and with our contemporary audiences in mind. But, as I discovered at Oberlin, having a good idea of Bach’s circumstances, knowing what was physically and musically possible for him, and being aware of his goals—his desire to clarify, to instruct, to be understood, to get his message across—has really helped me to sort out what is good and necessary in what I learned at BPI. Bach was not only a genius; he was a practical, practicing musician. Knowing what he heard, and how he did it, can only improve our performances of his work.

Why Did Bach Compose the Mass in B Minor

Not until I moved to Chicago for graduate school did I begin to understand that the Lutheranism I knew bore only a faint resemblance to that practiced in Bach’s time.

I grew up in a fairly segregated atmosphere: most Roman Catholics lived on the east side of town and attended Catholic school, while the rest of us, primarily Lutherans, lived on the west side and attended public school. The two groups were not, strictly speaking, enemies, but our friends were within our own group, we participated in our own communal activities, and we did not have much to do with one another. I never set foot in the Catholic church; we stayed clear of masses, along with priests and nuns and the Virgin Mary. I assumed no kinship between what Lutherans did on Sunday, and what the Catholics did. My public school music teachers were Lutheran, and my piano teacher was a Lutheran; in my mind, music was a Lutheran thing. The Lutheran hymnal had hymns by J.S. Bach—he was “ours,” and we claimed him, though we knew little about him. I had no idea at all that Bach had composed several settings of the mass, and that these settings were in Latin, the same language used at our town’s Catholic church. I attended a Lutheran college, where courses in religion and music history taught me something about Roman Catholicism and broadened my knowledge of the mass as a liturgical structure and as the basis for extended musical form; but my viewpoint remained pretty parochial. Not until I moved to Chicago for graduate school did I begin to understand that the Lutheranism I knew bore only a faint resemblance to that practiced in Bach’s time. Lutherans continue to claim Bach—some refer to him as the “fifth evangelist,” while others stress a symbolic father-son relationship between him and Martin Luther: Luther clarified the faith, and Bach set it to music. Some writers even describe a “Lutheran” approach to the interpretation and performance of Bach’s music.

By all accounts, Bach was deeply religious. Although his professional responsibilities throughout his life included obligations to secular as well as religious authorities, and his surviving compositions reflect this career duality, the evidence revealed in his letters, in his professional trajectory, and in the very nature of his activities in liturgical composition and performance, leave little reason to doubt his fundamental piety and spirituality. There is little doubt, as well, that he was thoroughly Lutheran in his theology. But Lutheranism as Bach experienced it was more than theology—it was the state church, a source of power and preferment, and it shared a good deal of space with secular authority. When Bach compiled the first half of his mass—called the Missa, it consisted of the Kyrie and Gloria sections of the Ordinary— he was not only working comfortably within the traditions of the Lutheran Church (which continued, post-Reformation, to refer to the Eucharist as the “mass”), he was also seeking advancement from the court at Dresden, to whom he presented his Missa as a gift, in 1733. This limited (but complete) work, approximately one-half as long as the completed Mass in B Minor, did indeed receive a liturgical performance by the Dresden kapelle, and ultimately won for Bach the worldly preferment and protection he was seeking.

By all accounts, Bach was deeply religious. Although his professional responsibilities throughout his life included obligations to secular as well as religious authorities, and his surviving compositions reflect this career duality, the evidence revealed in his letters, in his professional trajectory, and in the very nature of his activities in liturgical composition and performance, leave little reason to doubt his fundamental piety and spirituality. There is little doubt, as well, that he was thoroughly Lutheran in his theology. But Lutheranism as Bach experienced it was more than theology—it was the state church, a source of power and preferment, and it shared a good deal of space with secular authority. When Bach compiled the first half of his mass—called the Missa, it consisted of the Kyrie and Gloria sections of the Ordinary— he was not only working comfortably within the traditions of the Lutheran Church (which continued, post-Reformation, to refer to the Eucharist as the “mass”), he was also seeking advancement from the court at Dresden, to whom he presented his Missa as a gift, in 1733. This limited (but complete) work, approximately one-half as long as the completed Mass in B Minor, did indeed receive a liturgical performance by the Dresden kapelle, and ultimately won for Bach the worldly preferment and protection he was seeking.

The larger question about Bach’s purpose is reflected in his “completion” of the Mass in the last years of his life. He in some respects pulled back from the day to day responsibilities of his position in Leipzig, and put his energy into the completion of major, somewhat theoretical works: Musical Offering, The Art of Fugue, and Mass in B Minor. In these works, he seems intent not only on establishing his own legacy, but in creating a veritable encyclopedia of western European musical styles, forms, and procedures.

It seems clear that Bach never intended his Mass for liturgical use—clocking in at two hours without a break, it is simply too long. Rather, it appears to be what Bach scholar Christoff Wolff calls the summa summarum of Bach’s artistry. Wolff goes on to say, “We know of no occasion for which Bach could have written the B-minor Mass, nor any patron who might have commissioned it, nor any performance of the complete work before 1750. Thus, Bach’s last choral composition is in many respects the vocal counterpart to The Art of Fugue, the other side of the composer’s musical legacy. Like no other work of Bach’s, the B-minor Mass represents a summary of his writing for voice, not only in its variety of styles, compositional devices, and range of sonorities, but also in its high level of technical polish. “

Performances of the work reflect not only our perceptions of Bach’s beliefs and intentions, but our personal entry to the work. The first complete productions of the Mass, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, stressed its magisterial qualities—depicting Bach as an extraordinary man who communed with God on a level beyond human emotion and expression. Near-universal acceptance and practice of the Christian faith, which influenced all thought and politics of Bach’s time, still held a great deal of sway 100 years later. Bach was seen as an almost sacred prototype for the heroic figure later realized in Beethoven— the first complete performance of the Mass, in 1859, was actually inspired by the success of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. Many modern performances stress, instead, Bach’s humanity, his imperfection, his kinship with musical tastes and procedures of his own time. This latter approach has invited participation by musicians who do not profess any religious creed, yet find the work to be universally compelling and uplifting. I suspect the Mass may be the most comprehensive, unifying work by any composer— Bach’s attempt to depict the universality behind both his private spirituality and the religious expression of his time. Albert Schweitzer described the work as one in which the sublime and intimate co-exist side by side, as do the Catholic and Protestant elements, all being as enigmatic and unfathomable as the religious consciousness of the work’s creator.

Black with Notes

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move.

Chorale is seven rehearsals into its preparation for our March 26 performance of Bach’s Mass in B Minor. I am grateful for so extended a rehearsal period-- every singer in the group benefits from repeated exposure to this complex, difficult music.

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move, aiming for the next harmonic arrival point, then taking off again once it is reached. The overall effect is—page after page of notes, thousands of them; how does one organize them? Where does one begin in breaking them down into comprehensible groupings, in assigning emphasis, ebb and flow, in such a way that they all make sense, all get heard, all matter and contribute positively, without just canceling one another out in a cloud of sound?

A typical Bach score is black with notes. Harmonies outlined in the basso continuo rarely rest, and pitches above them change constantly to keep up. Performers become accustomed to this– one is always on the move, aiming for the next harmonic arrival point, then taking off again once it is reached. The overall effect is—page after page of notes, thousands of them; how does one organize them? Where does one begin in breaking them down into comprehensible groupings, in assigning emphasis, ebb and flow, in such a way that they all make sense, all get heard, all matter and contribute positively, without just canceling one another out in a cloud of sound?

The first movement of the Mass in B Minor, Kyrie I, immediately plunges us into this “Bach problem.” After a 4-bar, homophonic introduction, the movement unfolds in thirteen independent musical lines, in addition to the continuo line. Singers aren’t accustomed to thinking much about instrumental lines– we see five vocal lines, and figure our job is to make sense of those; it surprises us to learn that the instruments do more than just accompany us, and have their own, independent lines, weaving in and out of what we are doing. Fundamentally, there is no hierarchy; each line contributes equally to Bach’s structure and texture. We need to find hierarchy within our own lines—periods of higher energy, balanced with periods of relaxation; figures which require pointed, staccato or marcato emphasis, and figures with require legato; passages of a more soloistic character, and passages of background accompaniment. If we don’t find hierarchy within our own parts, relative to the rest of what is going on, we end up sound like a beehive on a warm day, lots and lots of buzzing.

A Chorale member commented on a performance of the Mass with his college choir, that “we just tried to sing the notes; we never did anything with all this articulation stuff.” I know what he is talking about: even with a high percentage of singers who have previously performed the work, Chorale struggles to find pitches and rhythms; vocal quality, articulation, phrasing, would be complete non-starters, were I not constantly stopping to point them out, dictate them, and work on them. The Bärenreiter piano-vocal scores we sing from are “clean”—they include very little that Bach himself did not notate in his own scores, and Bach did not customarily notate much in the vocal lines. The instrumental lines are fairly marked up, following Bach’s own score and parts, and many of these marks have been transferred to the piano reduction in the singers’ scores—but singers are not prone to look down to the piano line: following their own line is about all they accomplish at this point. So we transfer the markings to the vocal parts in rehearsal, and then rehearse characteristic phrase articulations, ornaments, etc. Taken by themselves, these articulations can seem pretty mechanical and not awfully graceful; they have to be performed with understanding and within the context of the vocal line, and this is extremely difficult– Bach demands a great deal. I urge the singers to listen to the 2015 Gardiner recording, as an example of the sort of articulation and expressiveness we are after; but it takes a great deal of familiarity for them to internalize these gestures and allow them to mean something, rather than just perform them mechanically. The individual lines have to flow; they have to alter in emphasis and adjust to the volume, the surrounding parts, the intensity of individual passages; and this requires far more than mechanical competence and repetition.

I ran across the following passage by Martin Luther yesterday: “This life therefore is not righteousness, but growth in righteousness, not health, but healing, not being but becoming, not rest but exercise. We are not yet what we shall be, but we are growing toward it, the process is not yet finished, but it is going on, this is not the end, but it is the road. All does not yet gleam in glory, but all is being purified.” Very much the same thing can be said about learning to sing this music-- our rehearsal period is a kind of pilgrimage, a process. With every preparation Chorale does of this “greatest of all works,” we draw closer to the essential truth of this great composer and his overwhelming accomplishment. The Mass in B Minor is not only the best we humans can come up with, but it is transcendingly good, and we are a part of this transcendent goodness; there is more to us, more to hope for and plan for and celebrate, than the brutality, the violence, the hatred, which we daily confront in one another. A human being, one of us, composed this monumental and life-transforming work; just knowing that, should make us better people.

Scapulis suis, Chorale's 15th Anniversary Commission

Centeno’s harmonic and melodic language are diatonic and accessible; but his phrase structure and rhythmic vocabulary are complex, irregular, and somewhat unsettling.

In commemoration of our 15th anniversary, Chorale commissioned Spanish composer Javier Centeno to compose an a cappella choral work for us. As text, I selected the Offertory from the First Sunday in Lent, which is actually a reordering of Psalm 91:

In commemoration of our 15th anniversary, Chorale commissioned Spanish composer Javier Centeno to compose an a cappella choral work for us. As text, I selected the Offertory from the First Sunday in Lent, which is actually a reordering of Psalm 91:

Scapulis suis obumbrabit tibi et sub pennis ejus sperabis scuto circumdabit te veritas ejus.

He will overshadow thee with his shoulders: and under his wings thou shalt trust. His truth shall compass thee with a shield.

Dicet Domino: Susceptor meus es non timebis a timore nocturno a sagitta volante per diem.

He shall say to the Lord: Thou art my protector, thou shalt not be afraid of the terror of the night [or] of the arrow that flieth in the day.

Quoniam Angelis suis mandavit de ut custodiant te in omnibus viis tuis.

For he hath given his angels charge over thee; to keep thee in all thy ways.

I love this text, especially the first section: I automatically conflate it with Movement 60 of Bach’s Matthew Passion, in which the alto soloist describes Jesus standing with outstretched hands, and choir II has those fiendish interjections—“Wohin? Wohin? Wo?”—where? Later, the alto sings "ruhet hier, ihr verlassnen Küchlein ihr, bleibet in Jesu Armen." “Rest here, you lost chicks, come home to my arms.” One of the most precious moments in the entire Passion. I find here a rare Christian image of God as feminine, nurturing, protective. So I am exploring this new work in different ways, trying to feel how the composer expresses this image, what about his music and text setting is special and personal. Centeno’s harmonic and melodic language are diatonic and accessible; but his phrase structure and rhythmic vocabulary are complex, irregular, and somewhat unsettling, effectively questioning and undermining the comfort and assurance implied by his beautiful sounds. One senses trouble, danger—nothing specific, just a suspicion that things are not as lovely as they seem. A soprano solo arches over the murmuring, brooding sounds of the choir at crucial points-- and not just the number of choristers, but the complex writing itself, requires a powerful, spinto-like sound throughout the soloist’s range—nothing delicate or boy-treble about it. One senses in this solo the image and character of God, fighting for her chicks, protecting them from the coming storm. One particular line of the text, “scuto circumdabit te veritas ejus “ (His truth shall compass thee with a shield), serves as a recurring refrain, pulling the listener back to comfort and assurance. The piece ends with two pages of wordless “Ah” from both soloist and choir, as a sort of coda.

The choir and I have enjoyed digging into this. It is not like most of the music we sing, which tends to be more intellectually and logically structured; this piece is built on emotion and feeling, and as such is somewhat more difficult to us to grasp. After several weeks of rehearsal, I feel that we are finally getting it-- and find the effort immensely rewarding. I can tell that Scapulis suis is a wonderful addition to the choral repertoire-- and feel very privileged that Chorale gets to sing it first.

The Wit and Wisdom of Mr. Shaw

"The arts, like sex, are too important to leave to the professionals."

"The arts, like sex, are too important to leave to the professionals." I heard this statement several times, over the years I sang with Robert Shaw. Musicians throughout the world will observe the 100th anniversary of Shaw’s birth on and around April 30 of this year, and many will share memories of his pithy anecdotes and one-liners. I will especially remember this phrase; it does stick with one. And it references directly the work I do: making choirs out of, and for, amateurs.

"The arts, like sex, are too important to leave to the professionals." I heard this statement several times, over the years I sang with Robert Shaw. Musicians throughout the world will observe the 100th anniversary of Shaw’s birth on and around April 30 of this year, and many will share memories of his pithy anecdotes and one-liners. I will especially remember this phrase; it does stick with one. And it references directly the work I do: making choirs out of, and for, amateurs.

Amateur, in its radical and most profound sense, means lover. Amateur musicians love what they do—whether they are paid to do it, or not. Members of Chicago Chorale sing in the group because they love the repertoire, they love getting together to sing it, they love working hard to get it right. I am able to program massive works—the Bach Passions, for instance, the major masses and requiems, the intricate and fiendishly difficult a cappella works of Arvo Pärt and Herbert Howells, the Rachmaninoff All Night Vigil on which we are currently working—because Chorale’s singers love these works, and are willing, even happy, to sweat through the long hours required to learn them, to become comfortable and fluent performing them. I am able to spend the time with the performers that the works require, and our audiences are able to hear the results of our work for reasonable ticket prices.

Chorale exists at least as much for its members, as it does for its audience. I don’t doubt for a moment, that choral singing, especially good, conscientious choral singing, is one of the best things one can do with ones time and energy. Grappling with the best that Bach has to offer brings one closer to the godlike mind and vision of Bach himself-- a state to which all of us should aspire. Embracing the passion and commitment of Rachmaninoff first-hand, sharing in the other-worldly vision of Pärt, can only change us in good ways-- and change our relationship with our culture, and the entire world around us.

Professional music—music for which performers are paid—is a good thing. I have been happy to perform at a high enough level, personally, to be paid for what I do. I am grateful. And I know the pitfalls of such professionalism. I have too often gone into performances under-rehearsed because management could not afford sufficient rehearsal time; I have too often sung with and under musicians whose work I did not enjoy or respect, because I needed the money offered me. I have too often performed repertoire which did not seem worth the effort expended to present it, and about which I felt little pride or sense of accomplishment. I have too often entertained the nagging feeling that the magic I experienced as a child, and as a student, when the vast and wonder-filled world of music opened up to me, was no longer a major part of what I was doing.

I never feel this disappointment when I work with Chorale. Idealism, and love, predominates in this work. I see the awakening of wonder in the eyes of my singers, experience the grateful response of our audience, and I know that what we are doing is right where I want to be. Mr. Shaw had it right.

It's All About the Language

Language sets vocal music apart from instrumental music—and may even turn it into an entirely different art form. Singers undergo training and preparation that is very different from that experienced by instrumentalists.

Language sets vocal music apart from instrumental music—and may even turn it into an entirely different art form. Singers undergo training and preparation that is very different from that experienced by instrumentalists. We learn, and warm up with, the basic Italian vowels—a, e, i, o, and u—but that’s only the beginning; not only do we have many more vowels than these to learn, but we have to relearn even the basic five as we move from language to language. [a] in Italian is very different from [a] in Russian. And then there are the consonants, bewildering enough in our own language, but really mystifying when moving far afield-- “what do you mean, isn’t T just T? And L just L? ” The looks of blank incomprehension that greet critiques of the manner in which T and L are pronounced, are priceless.

And the various sounds of language, the phonemes, are just the beginning. Singers have to sing as though they understand what the language means, too. Ideally, all of the singers in a choir would be linguists, reading and speaking numerous languages, ears and brains open to new sounds, new meanings. The truth is far from that. So, when tackling a major work in a foreign language, the conductor has to arrange, in advance, to spend a considerable amount of rehearsal time on extra-musical matters, and to enlist extra-musical help. The work we are currently preparing, Rachmaninoff’s Vespers, sets a text entirely in Old Church Slavonic—a language in which I have no particular proficiency. The editor of the edition from which we are singing has devised a  helpful, comprehensive transliteration and pronunciation system—he even sends out a CD of the text spoken by a knowledgeable speaker—but Chorale goes further, and has a language coach, Drew Boshardy, present at all of our rehearsals (he also sings with the group), who reads the text, has the singers repeat it, corrects their errors, listens to them sing it, corrects them again—and is vigilant throughout the rehearsal process, jumping in with comments whenever he hears something questionable. He also points out the meanings of specific words, and guides us in word accents and the overall mood of particular phrases.

helpful, comprehensive transliteration and pronunciation system—he even sends out a CD of the text spoken by a knowledgeable speaker—but Chorale goes further, and has a language coach, Drew Boshardy, present at all of our rehearsals (he also sings with the group), who reads the text, has the singers repeat it, corrects their errors, listens to them sing it, corrects them again—and is vigilant throughout the rehearsal process, jumping in with comments whenever he hears something questionable. He also points out the meanings of specific words, and guides us in word accents and the overall mood of particular phrases.

Drew has a degree in Slavic languages from the University of Chicago, and his help is invaluable; if we didn’t have him, we’d have to find someone much less convenient. We make the same sort of arrangements when we sing in German, French, Norwegian; care for language is a very important part of the Chicago Chorale experience. Agreement on vowel color is essential to good intonation; clear, uniform consonants define rhythm. And the meaning of the text determines interpretation. Even if listeners in the audience are not aware of what we are doing, or if a particularly juicy acoustical space obscures the details we so carefully stress, the precision and care with which we present the language, and the music, still comes through. We sound together, and committed.

Singers, and choirs full of singers, stand to learn a great deal from instrumentalists: from their precision, their intonation, their careful control of dynamics and color. Often, when preparing the major Bach works, I talk in rehearsal about the way in which string players would accent or phrase a certain passage, simply because of the characteristics of their instruments. But I have often noticed, as well, in the instrumentalists’ printed parts, that some players write the words in at crucial points, to guide them in the choices they make—and I rejoice to see this. Singers bring something very special to a musical preparation. We all profit through learning from one another.

Embarking on Sergei Rachmaninoff's Vespers

Russian choral music culminates in Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil.

After a successful autumn (the Chicago Tribune’s music critic John Von Rhein designated our Arvo Pärt at Eighty concert “the Year’s Finest Choral Performance”), Chorale has embarked on preparations for our March presentation of Rachmaninoff’s Vespers. As preparation for this event, I quote from program notes compiled by Chorale alumnus Justin Flosi, seven years ago: “Written at the height of the renaissance of Russian sacred choral music, Rachmaninoff’s few sacred works remain the unrivaled jewels in the crown of the Orthodox musical tradition and epitomize the work of the New Russian Choral School. Composers of the school (including Kastalsky, Gretchaninoff, and Chesnokov) drew their inspiration from Old Church Slavonic chant and Russian choral folk song, departing from a century and a half of domination by Italian and German models. Led by musicologist Stepan Smolensky, who headed the Moscow Synodical School of Church Singing and pioneered the historical study of ancient chant, these composers created an entirely Russian choral style marked by an endless array of dynamic nuances and choral timbres.

“Rachmaninoff’s Vespers (All-Night Vigil, op. 37) was composed over just two weeks in January and February of 1915 and dedicated to Smolensky, the composer’s tutor. Johann von Gardner has proclaimed it a “liturgical symphony,” and indeed, Rachmaninoff masterfully exploits the New School’s technique of “choral orchestration,” varying the choral color extensively, dividing the choir into as many as eleven parts, calling for precise articulations, and dictating a vivid spectrum of dynamic gradations. From the tradition of Russian folk song, Rachmaninoff borrows the technique of “counter-voice polyphony,” skillfully integrating into his composition parallel voice-leading, melodic lines above a drone, and imitation between a constantly changing number of voices. And yet, Rachmaninoff’s dazzling technique never calls attention to itself; rather, it serves at all times to sustain the sacred text in its position of prime importance.

“Rachmaninoff’s Vespers (All-Night Vigil, op. 37) was composed over just two weeks in January and February of 1915 and dedicated to Smolensky, the composer’s tutor. Johann von Gardner has proclaimed it a “liturgical symphony,” and indeed, Rachmaninoff masterfully exploits the New School’s technique of “choral orchestration,” varying the choral color extensively, dividing the choir into as many as eleven parts, calling for precise articulations, and dictating a vivid spectrum of dynamic gradations. From the tradition of Russian folk song, Rachmaninoff borrows the technique of “counter-voice polyphony,” skillfully integrating into his composition parallel voice-leading, melodic lines above a drone, and imitation between a constantly changing number of voices. And yet, Rachmaninoff’s dazzling technique never calls attention to itself; rather, it serves at all times to sustain the sacred text in its position of prime importance.

“The All-Night Vigil service was introduced to Russia in the fourteenth century. In the words of Vladimir Morosan, it is a “curious liturgical concatenation” combining the services of Vespers, Matins, and Prime. Celebrated on the eves of holy days, it lasted from sunset to sunrise in the medieval church (although modern reforms have shortened the service). Remarkably, Rachmaninoff sets the entire thing—all fifteen hymns, psalms, and prayers of the Resurrectional Vigil. Though deeply spiritual, Rachmaninoff was at odds with the organized religious establishment (which opposed his marriage to his first cousin, Natalie Satin) and not intimately familiar with the traditional musical settings of the Church’s liturgy. This may help explain his original and inventive approach in the All-Night Vigil.

“Rachmaninoff’s use of melodic material is both innovative and exhaustive, at once original and steeped in tradition. Drawing from all three ancient chant traditions (Znammeny, meaning “notated with neumes,” Greek School, and Kiev School), nine of the fifteen movements are based on actual chant melodies. For the remaining six, Rachmaninoff composed new material, inspired by chants; he called these movements “conscious counterfeits.” The resulting fusion of old and new material overflows with an intensely expressive melodic richness. As the voices by turns rise heavenward and sink into the depths, Rachmaninoff portrays the essence of humankind’s worship of the Divine, from its most exuberant exultation to its most sincere supplication.

“Such sumptuous sounds illumine the epic grandeur of the events commemorated in the All-Night Vigil. After the opening call to worship, the Vespers section depicts the Creation and the incarnation of Christ. The Matins portion turns to a celebration of the central event in Christian cosmology: Christ’s resurrection. Thus, spiritually, liturgically, textually, and musically, the work operates on an immense and expansive scale. Francis Maes positions it at the summit of the Orthodox tradition, stating that, “The work satisfies all liturgical demands, but goes beyond them in the same way that Bach’s B Minor Mass and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis do.” As those works serve as capstones to their respective traditions, so Russian choral music culminates in Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil.”

I could not have said it nearly so well.

Why did Bach, a Lutheran, compose a mass?

Lutherans continue to claim Bach—some refer to him as the “fifth evangelist”— and others stress a symbolic father-son relationship between him and Martin Luther: Luther clarified the faith, and Bach set it to music.