Advent Vespers 2017

This Sunday, a select group of Chorale’s regular singers will sing the choral portions of Solemn Vespers for the Second Sunday in Advent, along with the monks of the Benedictine Monastery of the Holy Cross, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood.

This Sunday, a select group of Chorale’s regular singers will sing the choral portions of Solemn Vespers for the Second Sunday in Advent, along with the monks of the Benedictine Monastery of the Holy Cross, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. We do this each year. This service provides us with the opportunity to learn repertoire we would not normally do in a concert setting, in a peerless, unearthly acoustic space; it gives us the experience of singing this music in the sort of setting for which it was originally intended by its composers; and we are happy to work with the monastery, which has so graciously supported our programs in the past, and allows us to record in their chapel. December 10, this coming Sunday, at 5 PM, we will sing music by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: his double motet Canite tube/Rorate caeli; his setting of the Advent hymn Conditor alme siderum; and Magnificat in mode 8. In the velvety, enveloping acoustics of the monastery’s chapel, it should be a timeless break from the everyday stresses and obligations of our daily lives, to just sit still, let Palestrina’s glorious music surround and enter us, and ponder the mystery of the Advent season. The service (it is not, strictly speaking, a performance) is free and open to the public. We do invite donations, to support the work of the Monastery and of Chicago Chorale.

After a break for the Christmas and New Year holidays, Chorale will reconvene in January to begin rehearsals for our March 25 (Palm Sunday) presentation of Mozart’s Requiem, in the completion by Robert Levin. Mozart died while in the midst of working on this masterpiece; his wife, Constanze, had the work completed in secret by Mozart’s assistant, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, in order to collect the commissioning fee which had been promised for the completed work. Later scholars and musicians have questioned Süssmayr’s work, and it has become a cottage industry, to imagine, and execute, what Mozart himself must have intended. Helmuth Rilling and the Internationale Bachacademie of Stuttgart, with support from the Oregon Bach Festival, commissioned Harvard theorist Robert Levin to do a completion, which has gained a good deal of recognition and favor amongst musicians in the years since it was published and made available. As a member of the Oregon Bach Festival chorus, I participated in early performances of Levin’s version, with Mr. Levin present, advising us, making changes, consulting with Mr. Rilling . I also performed it on tour in Israel with the Gächinger Kantorei and the Israel Philharmonic, under Mr. Rilling’s baton, in concerts commemorating the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth, in January, 2006. I am sold on Mr. Levin’s completion, and am happy to have this opportunity to present it to the Chicago audience. We have a stellar quartet of soloists: Tambra Black, soprano; Karen Brunssen, alto; Scott Brunscheen, tenor; and David Govertsen bass; and an outstanding orchestra, contracted for us by Anna Steinhoff.

This Sunday, a select group of Chorale’s regular singers will sing the choral portions of Solemn Vespers for the Second Sunday in Advent, along with the monks of the Benedictine Monastery of the Holy Cross, in Chicago’s Bridgeport neighborhood. We do this each year. This service provides us with the opportunity to learn repertoire we would not normally do in a concert setting, in a peerless, unearthly acoustic space; it gives us the experience of singing this music in the sort of setting for which it was originally intended by its composers; and we are happy to work with the monastery, which has so graciously supported our programs in the past, and allows us to record in their chapel. December 10, this coming Sunday, at 5 PM, we will sing music by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: his double motet Canite tube/Rorate caeli; his setting of the Advent hymn Conditor alme siderum; and Magnificat in mode 8. In the velvety, enveloping acoustics of the monastery’s chapel, it should be a timeless break from the everyday stresses and obligations of our daily lives, to just sit still, let Palestrina’s glorious music surround and enter us, and ponder the mystery of the Advent season. The service (it is not, strictly speaking, a performance) is free and open to the public. We do invite donations, to support the work of the Monastery and of Chicago Chorale.

After a break for the Christmas and New Year holidays, Chorale will reconvene in January to begin rehearsals for our March 25 (Palm Sunday) presentation of Mozart’s Requiem, in the completion by Robert Levin. Mozart died while in the midst of working on this masterpiece; his wife, Constanze, had the work completed in secret by Mozart’s assistant, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, in order to collect the commissioning fee which had been promised for the completed work. Later scholars and musicians have questioned Süssmayr’s work, and it has become a cottage industry, to imagine, and execute, what Mozart himself must have intended. Helmuth Rilling and the Internationale Bachacademie of Stuttgart, with support from the Oregon Bach Festival, commissioned Harvard theorist Robert Levin to do a completion, which has gained a good deal of recognition and favor amongst musicians in the years since it was published and made available. As a member of the Oregon Bach Festival chorus, I participated in early performances of Levin’s version, with Mr. Levin present, advising us, making changes, consulting with Mr. Rilling . I also performed it on tour in Israel with the Gächinger Kantorei and the Israel Philharmonic, under Mr. Rilling’s baton, in concerts commemorating the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth, in January, 2006. I am sold on Mr. Levin’s completion, and am happy to have this opportunity to present it to the Chicago audience. We have a stellar quartet of soloists: Tambra Black, soprano; Karen Brunssen, alto; Scott Brunscheen, tenor; and David Govertsen bass; and an outstanding orchestra, contracted for us by Anna Steinhoff.

Sunday, March 25, 3 PM, at St. Benedict’s Parish, 2215 W. Irving Park Road. Things become very busy at that time of year, and schedules fill up; be sure to put us in your calendar now. You won't want to miss this.

Sisu: Part 2

Guest post by Managing Director Megan Balderston

Those of you who have read Bruce’s Blog over the years may recall his December, 2010 blog about the Finnish word, “sisu.” http://www.chicagochorale.org/sisu-and-chicago-chorale/

At a recent rehearsal for a musical I performed in, after failing once again at a particular dance pattern that was coming naturally and effortlessly to only about two people, my friend looked at me and groaned, “Why do we come here night after night, just to be yelled at because we can’t do this correctly?” The truth is, many of us who have a love of musical theater will never come even close to being Sutton Foster. Why do we do it, then? I have been thinking about that very question, quite a bit, as it relates to all of my various avocations and hobbies. They have this question in common.

There are a number of Chorale singers who are involved with the sport CrossFit, and I am one of them. I regularly attend our gym’s 6:00 am class, which right now is made up mostly of people my own age. If you don’t know (and I’m not sure how you don’t, as we CrossFitters have a reputation of talking about the sport ad nauseum) CrossFit gyms are notoriously spartan. No spas, no mirrors, just equipment and mats. Our class is small but mighty, average age is 50, and we have the following in common: a love for 80’s music; we may not like the individual exercises, but we like the way they make us feel; we believe in building on our strengths and trying to develop our weaknesses; and the camaraderie helps. In fact, one day as Bruce and I were chatting about it, he remarked, “It sounds absolutely miserable but they know how to build a program so that you all have fun.” Indeed, painted on the wall of our gym is the following list: 1. Check your ego at the door. 2. Show up and do the work. 3. Nobody cares what your time is. 4. Everybody cares if you cheated. 5. Effort gains respect.

What do these disparate activities have to do with choral singing, and each other, let alone the concept of sisu? Quite a bit, as it turns out: they all have the common theme of "deciding on a course of action and then sticking to it despite repeated failures."

Two weeks ago I was attempting to get a “PR” (personal record) on a back squat: this is a lift where you place a barbell across your shoulders, lower into a squat, and then press back up so that you are standing upright. As a novice to intermediate level lifter, I was thrilled to increase my “PR” by 5 pounds. So I thought, why not add another 10 pounds and see how I do? Alas, I could not stand up again; I got stuck “in the hole” at the bottom of the squat. This is a bit humiliating. However, one of my gym buddies reminded me: you can’t improve, if you don’t first attempt more and fail.

Choral singing, the way Chicago Chorale does it, is also about this kind of mindset. I suppose we could pick easier repertoire, or a less rigorous schedule, or do any number of things differently so that we wouldn’t be presenting concerts that require so much effort. So much grit. So much sisu. But I believe that would take away exactly the kind of determination that makes Chorale a special group within the landscape of Chicago’s many musical groups, both amateur and professional. We care so much, and if we have to white-knuckle some things, and demand more out of ourselves to present a beautiful program, that is where we would rather be.

Do I love failing? Noooo, that’s not it. But I do find that I love the process of learning something new, and showing myself that I can do things I never dreamed I could. I probably strangely love the cycle of repetition, humiliation, exaltation, despair, laughter, and renewed confidence. Bruce sent a note around to the choir this week, in which he said the following: "I want us to be clear-eyed, clear-eared, objective, self-critical, idealistic; I want us to be, and do, the very best that is in us."

I’m with Bruce. As a 48-year-old woman I do not need to lift weights, to float a high F, to tap dance, or to open myself up to scrutiny and possible humiliation by putting myself on the line in any number of ways. And yet I think of all of the wonderful things I would be missing if I did not: it would be a quieter, and less joyful life. We all owe it to ourselves to explore what is the best in us, whether or not we will become the best in the world. Effort gains respect, for sure, but more importantly effort gains self-respect. Sisu. The determination required for the journey is as special as the end product. I hope you will join us when we present our concert on June 10th, and hear what "sisu" sounds like.

Palestrina: The "Savior of Music"?

Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

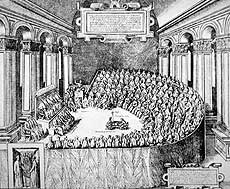

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the

In addition to The Peaceable Kingdom, Chorale will sing Palestrina’s Pope Marcellus Mass on our June 10 concert. The latter work was composed in honor of Pope Marcellus II, who reigned for only three weeks, in 1555; Palestrina is likely to have composed it in 1562, a couple of popes later. It is undoubtedly the most famous of Palestrina’s choral compositions, both for its undeniable beauty, and for a persistent legend which grew up around its composition.

The Council of Trent (1545-63) was convened in response to the Protestant Reformation, to bolster church orthodoxy and eliminate internal abuses. The nature and uses of church music were an important topic of this council, especially of the third and closing sessions (1562-63). Two issues in particular concerned the participants: first, the utilization of music from objectionable sources, such as secular songs fitted with religious texts, and masses based upon songs with lyrics about drinking and sex; and second, the  increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

increasingly elaborate, complex polyphonic texture of the contemporary church music, popular with contemporary composers, which tended to obscure the words of the mass and sacred hymns, interfering with worshipers’ religious devotion. Some sterner members of the Council argued that only plainsong (a single line of music) should be allowed, and polyphony banned altogether. On September 10, 1562, the Council issued a Canon declaring that “nothing profane be intermingled [with] hymns and divine praises,” and banishing “all music that contains, whether in singing or in the organ playing, things that are lascivious or impure.”

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

Palestrina was a brilliant practitioner of polyphonic composition; but his career depended completely on church patronage. When Marcellus II died in 1555, his successor, Paul IV, immediately dismissed Palestrina from papal employment, and hard times ensued for him. Fortunately for Palestrina, Paul IV's death, just four years later, ushered in the era of Pius IV, who was more sympathetic to polyphony. In 1564, according to the legend (and two years after the actual copying of the Mass), Pius asked Palestrina to compose a polyphonic mass that would be free of all “impurities” and would thus silence the purists. Palestrina answered with the Pope Marcellus Mass, and its performance succeeded in establishing polyphonic music (and Palestrina) as the voice of the Church. Palestrina gave the Council what it wanted: clean, singable lines that allowed for clear declamation (and comprehension) of the text; and a smooth, seemingly uncomplicated, harmonically consonant vehicle for the sacred words. The Council participants were appeased, and church music was saved (or so the story goes); composers were allowed to continue to write polyphonic music.

It seems unlikely that the Pope Marcellus Mass was composed with the intent of saving music, or even that Palestrina’s name, career, and music came up in the Council’s discussions. No documentation exists to support such a role for him. Most likely, he was a career church musician who was willing to make a few minor adjustments to fit certain requirements because it was the sensible thing to do. Nonetheless, beginning almost immediately in 1564, Palestrina became “the savior of music,” and remained so through the later twentieth century. The Roman Catholic Church presented his compositional style as a model for good church music, and generations of music students studied his works, particularly this mass, as an example of what they should understand and emulate. Giuseppe Verdi said of the composer, “He is the real king of sacred music, and the Eternal Father of Italian music.” In James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses (1934), Joyce's friend Frank Budgen quotes him as saying "that in writing this Mass, Palestrina saved music for the church." Palestrina’s magisterial image was set in stone.

Chorale is finding the Pope Marcellus Mass to be a very rewarding project. The music is lovely, soothing, uplifting; it flows so naturally and effortlessly, one would imagine its composition to have been easy for the composer. The more deeply we delve into it, however, the more we discover Palestrina’s craft and skill, and the genius of his contrapuntal writing. I discover, myself, a similarity to Mozart’s music: a gracious, pleasing, untroubled surface, a kind of abstract perfection: but so difficult to describe and define, once one is inside it. It demands extraordinary skill and grace in performance; and yields, on its own, incredible richness and satisfaction. Palestrina, like Mozart, does not require our help; he requires our humility, our willingness to get out of the music’s way and let it speak for itself.